How Do I Make Sense Of The Book Of Revelation?

By Clement Harrold

Notorious for its complexity, the biblical book of Revelation presents an interpretive challenge to the most diligent of readers. Even St. Jerome, the renowned Scripture translator of the early Church, admitted to finding this book mysterious and perplexing.

Although some modern scholars have expressed skepticism, the traditional consensus is that the book of Revelation was written by John the Apostle, the same John who is typically identified as the author of the Fourth Gospel.

While living on the island of Patmos, located in the Aegean Sea off the coast of modern-day Turkey, John received the set of visions which make up the book of Revelation (see Rev 1:9). When exactly this took place is the subject of scholarly debate; while most scholars situate the composition of the book towards the end of the reign of the Roman Emperor Domitian (c. A.D. 95), a notable minority favor a date falling within the reign of Emperor Nero (A.D. 54-68).

In this blog post, we shall limit ourselves to offering a few tips which might make the book of Revelation a little more intelligible to the average reader, without pretending to answer every question or solve every difficulty.

Tip #1: Revelation = Apocalypse.

The book of Revelation—as it is usually called today—was written in Koine Greek, and the very first word of the text is Ἀποκάλυψις, transliterated as apokalypsis, which means “unveiling” or “revelation.” This Greek word carries over to Latin, with the result that the Latin Vulgate refers to the book simply as Apocalypsis Ioannis, “the Apocalypse of John.”

Given this, it used to be commonplace for people in the English-speaking world to refer to the book as “the Apocalypse.” In more contemporary English, however, this gets confusing because “apocalypse” and “revelation / unveiling” no longer mean the same thing.

Today, therefore, the English-speaking Church tends to prefer the title “Revelation,” on the grounds that this better captures the meaning of the original Greek name.

Tip #2: We don’t need to understand everything in the Bible.

This may sound like a startling claim, but it really isn’t! Even St. Peter, the first pope, admitted to finding some of St. Paul’s letters a little confusing (see 2 Pet 3:16). We should remember, too, that there is no eleventh commandment demanding that we read every part of the Bible, nevermind perfectly understand it.

In fact, traditional Christian practice has long been to favor particular biblical books when it comes to sharing the faith and growing in the spiritual life (most of us ought to spend more time meditating on the four Gospels than we do on Leviticus, for example). So if you go your whole life without knowing what’s going on in the book of Revelation, that’s not the end of the world—no pun intended!

Of course, this is not to suggest that there’s no value in coming to better understand and appreciate the final book of the Bible; there most assuredly is. But the point is that it isn’t essential for being a Christian.

Tip #3: The imagery is supposed to be complex.

The considerable degree of obscurity present within the book of Revelation is immediately obvious to anybody who tries to sit with the text. Yet it is important to bear in mind that in this kind of apocalyptic literature there is supposed to be a high degree of mystery, vivid use of symbolism, multiple layers of meaning, converging of the literal and spiritual, and so forth.

What this means in practice is that if you sit down to read Revelation 16 and you don’t feel like you understand everything that’s going on, that’s actually a sign that you’re reading the text correctly. In some real sense, the depth of mystery is there precisely in order to humble the reader and to invite her into a spirit of contemplation.

Part and parcel of this depth of mystery is the fact that many times in the book of Revelation the signs and symbols possess a dual or multiple meaning; for instance, oftentimes things will take place which are a reference to real historical events that occurred in the first century, while also pointing ahead to future eschatological realities that have not yet taken place.

Tip #4: It contains profound spiritual lessons.

Lest we get lost in the weeds of its bewildering imagery, it is worth noting that the book of Revelation also offers a rich series of spiritual reflections.

One place where these are especially prominent is in the famous letters to the seven churches described in chapters 2 and 3. Here we might ponder on the warning delivered to the church at Ephesus, for instance, which is praised for many good deeds, yet guilty of allowing these deeds to mask a deeper problem: “But I have this against you, that you have abandoned the love you had at first” (Rev 2:4). How often does this indictment apply in our own spiritual lives?

A similarly pithy lesson can be found in the well-known line voiced to the church at Laodicea: “Would that you were cold or hot! So, because you are lukewarm, and neither cold nor hot, I will spew you out of my mouth” (Rev 3:15-16). What are the areas of my life where I have allowed a lukewarm attitude to take hold?

The book of Revelation is also famous for its Marian themes. Beginning in 11:19 and continuing through chapter 12, Our Lady is presented as the new Ark of the Covenant who serves as God’s chosen instrument for bringing His Son into the world. Not only is she the queen of heaven, she’s also the devil’s arch-nemesis and our spiritual mother (see Rev 12:7).

Tip #5: It’s a liturgical book at its heart.

Why is Revelation the last book of the Bible? It’s the last book of the Bible because it reveals the end goal towards which the entirety of salvation history is ordered. And what is that end goal? It’s communion with God through right worship of the Holy Trinity:

After this I looked, and behold, a great multitude which no man could number, from every nation, from all tribes and peoples and tongues, standing before the throne and before the Lamb, clothed in white robes, with palm branches in their hands, and crying out with a loud voice, “Salvation belongs to our God who sits upon the throne, and to the Lamb!” (Rev 7:9-10)

In the book of Genesis, Adam and Eve sinned by attempting to become gods formed in their own image and likeness, rather than submitting to the one true God who created them in His. At the end of the book of Revelation, man’s proper relationship to God is definitively restored: God is adored and glorified, and mankind becomes not just like Him, but one with Him.

Strikingly, we are told that no Temple will be needed in this holy city, “because the Lord God Almighty and the Lamb are its Temple” (Rev 21:22). It is a city, in other words, with God at its beating heart, founded on the love of the Father and the wounds of the Lamb: wounds made present on earth through the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass, through which we can begin even now to participate in those heavenly realities which Revelation describes.

Bonus Tip #6: Get hold of a good commentary!

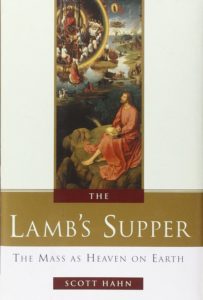

Revelation is a tough book, and Scripture was never meant to be read in isolation. Do yourself a favor and make use of a good commentary which will draw on the wisdom of Catholic tradition to guide you through the text. The Ignatius Catholic Study Bible (either Revelation itself or the whole New Testament) is a great place to start. Scott Hahn’s The Lamb's Supper: The Mass as Heaven on Earth is a classic exposition of the heavily Catholic liturgical elements in the book of Revelation. Other helpful resources are the Come and See Catholic Bible study series, and Michael Barber’s book Coming Soon: Unlocking the Book of Revelation and Applying Its Lessons Today.

Clement Harrold earned his master’s degree in theology from the University of Notre Dame in 2024, and his bachelor’s from Franciscan University of Steubenville in 2021. His writings have appeared in First Things, Church Life Journal, Crisis Magazine, and the Washington Examiner.

You Might Also Like

Bestselling author Scott Hahn sheds new light on the Mass, offering readers a deeper appreciation of the most familiar of Catholic rituals.

Of all things Catholic, there is nothing that is so familiar as the Mass. With its unchanging prayers, the Mass fits Catholics like their favorite clothes. Yet most Catholics sitting in the pews on Sundays fail to see the powerful supernatural drama that enfolds them. Pope John Paul II described the Mass as “Heaven on Earth,” explaining that what “we celebrate on Earth is a mysterious participation in the heavenly liturgy.”

The Lamb’s Supper reveals a long-lost secret of the Church: The early Christians’ key to understanding the mysteries of the Mass was the New Testament Book of Revelation. With its bizarre imagery, its mystic visions of heaven, and its end-of-time prophecies, Revelation mirrors the sacrifice and celebration of the Eucharist.