By Patrick Coffin

Patrick Coffin is the author of several books, including The Contraception Deception: Catholic Teaching on Birth Control, a comprehensive assessment of the Church’s sexual ethic. He is the host of The Patrick Coffin Show podcast, heard in over 100 countries.

This is the story of how "God came to our assistance and made haste to help us" (Psalm 69) amid the one trial every parent fears most. And He did so using ordinary events, people, and a striking series of coincidences. G.K. Chesterton called coincidences "spiritual puns," an insight as absorbing as it is relevant to our story. I’ll use only the first names of those involved.

Our first two girls, Mariclare, 4, and Sophia, 20 months, were born healthy, precocious, and happy. My wife, Mariella, and I wanted more little members on Team Coffin, so when we learned of number three, our refrigerator was happily bedecked with early ultrasound images framed between to-do lists and Crayola masterpieces. Like most parents of rambunctious kids, we took it for granted that all would be sweetness and light.

"There’s something wrong with the baby."

Things soon turned sour and dark when Mariella’s doctor found an anomaly in the baby’s tiny 12-week-old brain, along with some other signs that were described ominously as "unwelcome."

"There’s something wrong with the baby," Mariella told me that night, not quite able to hide tears. My husbandly bromides, "Don’t worry, Honey," and "Doctors aren’t always right," fell pancake flat. A specialist asked for another ultrasound.

On Divine Mercy Sunday, we sat drenched in worry when we glanced up at the cherished honeymoon photo of Pope John Paul II holding our hands in his. We promised him our prayers and asked for his. It seemed fitting to pray the nine-day Divine Mercy Chaplet of St. Faustina, John Paul’s fellow Pole who was canonized by him in 2000. Despite the daily chaplet, I found myself unable to concentrate at work and became easy prey to crying jags. I’d be sitting at a red light when suddenly my eyeballs felt like loose valves losing a battle against a gushing fire hydrant. Dads are hardwired to protect their children, especially the vulnerable ones. Here I could protect nothing.

Reaching out to us, our next-door neighbor Roz gave Mariella a Miraculous Medal that had touched the stigmata bandages of St. Padre Pio. Mariella took it to subsequent medical exams, the first of which was that dreaded ultrasound. It fell the day after the chaplet ended.

The lights were dimmed, and wobbly images of our baby flickered in the near dark, accompanied by a litany of scary medical jargon: The baby’s lateral ventricles were dilated; the finger positions and overall cranial shape were abnormal; the heart was surrounded by fluid and presented a ventricular septal defect, otherwise known as a hole. We heard the words "bad sign" a dozen times in five minutes. All indications pointed to trisomy 18, a rare and lethal genetic condition. I sat passively, holding my wife’s hand, pretending I wasn’t really hearing what I was hearing. Questions percolated, and not without anger: Hadn’t we prayed that this would turn out to be only a scare? Doesn’t God answer all prayers? Our other kids are in great health—why not this one?

Life Takes Letting Go

The monitor was switched off, and any hope to which I was clinging drained out of me like gold dust through a prospector’s fingers. Staring at the dead monitor, I half heard my wife tell me she had to go to the restroom and the doctor tell me to step into a nearby meeting room. I drifted ghostlike into the room with surreal images of our broken baby branded in my mind’s eye.

As I stepped toward the window and peered into the harsh noontime sunlight, waves of panic and dread, heartache, and the unremitting feeling that things were going to get terrifyingly worse—all of it stormed my ramparts. I shut my eyes tight, stood almost vibrating with grief, and stabbed at some semblance of a prayer for a sign of God’s presence.

Opening my eyes, I saw an absurdly large billboard angled straight at the window a block away. Blinking away tears, I could see a father and child holding hands jumping off a small cliff into a glittering lake. On the left, in bold letters, the billboard announced, "LIFE TAKES LETTING GO."

My soul was flooded with an unearthly consolation, as though the hurt was taken from the pain. I almost started laughing. Those jumbo words made me see that most of the hurt was rooted in my unwillingness to give my child over to the care of her true Father. Clinging tightly to that little baby, grasping desperately at strategies by which I could control things, I had spiritually strangled myself. Letting go was precisely what I dreaded most. But Life Himself seemed to be telling me that this was the best thing, the only thing, to be done. Talk about the divine sense of humor: I ask for a sign, I get a billboard.

As unlikely as it seems, that brief moment switched some inner default setting from Belief to Trust. As my friend Ross, a clinical psychologist, reminded me, believing in God is not identical to trusting in Him. It’s one thing to talk piously about being at the foot of the Cross, another to carry it, and still another to hang on it.

Amniocentesis was strongly advised, and we reluctantly agreed. While we normally prefer not to know our babies’ sex beforehand, we made an exception, found out it was a little girl, and promptly named her Naomi Rose. The results also brought news that sent our hopes soaring—the doctor was wrong about it being the death-dealing trisomy 18. Rather, Naomi’s ninth pair of chromosomes had a small extra portion of chromosomal material, a condition known as partial trisomy 9q, partial monosomy 9p. Only a few hundred cases are extant since being identified in 1973.

I relayed the way God was making His presence known to us—especially the billboard business—to my friend Chris, whom I had first met at his wedding nine years before. Chris urged me to write it all down. I didn’t realize that God was just getting started in the help department, nor that my former boss and mentor, Lisa, was praying that God would send us signs of His presence.

Spring gave way to summer, and summer faded into fall. I peppered my blog with updates on her condition and readers continued to flood me with pledges of prayer, support, and encouragement. Word spread and strangers from near and far began checking in on Naomi’s progress. Mariella’s obstetrician, Dr. Thomas, a practicing Catholic and father of nine, gave us a vial of holy water from Lourdes. Such gestures of support and empathy were overwhelming.

Our Lady of Triumph

Since Naomi persisted in breech position, she had to debut by C-section, which was scheduled for Thursday, September 13. A quick glance at the liturgical calendar showed that this was the memorial of Our Lady of Sorrows. Oh, great, I thought. Bad omen. Days after, owing to a scheduling glitch, the surgery was pushed to the next day, September 14, the Feast of the Triumph of the Cross, which fell on a Friday. The great Archbishop Fulton Sheen once wrote that "nothing ever happens out of heaven except with a finesse of all details." In a lovely example of such finesse, Naomi’s birth was set for 3 pm, the hour of mercy, on a Friday, on the Feast of the Triumph of the Cross. I wept.

Nature wept, too. September 14 brought the first rain in months. I went to morning Mass primed to hear some uplifting words on the glories of Christ’s victory, but our good pastor, Fr. Ed, mistakenly prepared an instructive homily on Our Lady of Sorrows. One must guard against over-interpreting random events, but this struck me as a sign that the Blessed Mother, who knew a thing or two about having a child in trouble, was walking with us.

Mariella and I headed to Hollywood Presbyterian/Queen of Angels Hospital, where a team of top-flight specialists awaited Naomi’s arrival. As she emerged into the light, what is normally a mother’s cup of blessing was for Mariella a chalice full of anxiety. An eerie silence attended Naomi’s birth. After the breathing ventilator was inserted, the tiny bundle Mariella carried beneath her heart for nine months had to be whisked next door to Children’s Hospital of Los Angeles, a most wrenching separation for her mother.

The same questions raced through our minds: Would Naomi be a special needs baby (our best-case scenario)? Was this illness the start of some lifelong cross we were being asked to carry? Was this parting only a rehearsal for a worse good-bye?

Our particular prayer to John Paul the Great was to resolve Naomi’s septal defect so we could meet her face-to-face. At birth, the hole was nowhere in sight. That evening I baptized her with the Lourdes water. Two days later, Fr. Ed made her a full member of the Church through Confirmation. Father showed me the old Latin/English prayer book he had dusted off to find the Rite of Confirmation for Baptized Children. The Latin inscription commemorating its approval in 1947 by Pope Pius XII was dated September 14, Naomi’s day of birth. Another spiritual pun to make Chesterton proud.

On Mariclare’s birthday, September 23, which happens to be the feast day of St. Padre Pio, I laid the blessed relic on Naomi’s forehead and asked that through his intercession, God’s perfect will would be done in her life. In seconds she began to stir. I came around to the other side of her bed and was stunned to see two milky blue eyes staring up at me. After nine slumber-like days, Naomi blessed us with a silent hello.

All Time Is Borrowed

Poignant for us was how beautiful Naomi became with each passing day. We had braced ourselves for the sight of misshapen ears, facial abnormalities—the whole works. And while at birth she showed clear signs of something being "off," despite the tubes, tapes, and wires, not a day went by that we didn’t use the use the word "angel" to describe her.

My parents and sister arrived from Nova Scotia, and Mariella’s mother came from Peru some days later. The extended family settled into a daily ritual of visits for as long as the NICU rules allowed, many of which were bent for us. Unspoken as it was, we knew these bittersweet visitations couldn’t go on indefinitely.

A neonatal MRI brought us the can’t-turn-back news. One of the head doctors, Dr. Claire, strode into the room, and I turned to introduce myself. Even before she spoke, a determined, sorrowful look in her eye drilled straight into me, telegraphing a single brute fact: Naomi was going to die.

Dr. Claire herself was very pregnant, and as she described the severity and finality of our daughter’s condition, she unconsciously stroked her belly as if to protect her baby from the news. Speaking in clipped, nervous tones, Dr. Claire pronounced that Naomi was not a candidate for any form of curative intervention. Her little heart still had a dangerous flaw called a coarctation, or narrowing, of the artery leading out of the heart. The drug used to treat it was only delaying the inevitable, and she would never be able to breathe on her own. Her brain ventricles were also catastrophically enlarged and her basal ganglia were riddled with necrosis. In layman’s terms, her brain couldn’t run her body.

It fell to us to decide the hour of our baby’s death. Sharing our fears with Dr. Thomas, he emphasized that ending extraordinary treatment would not be the cause of her death—that job was taken by trisomy 9. Whether one lasts 75 hours or 75 years, he was saying, we are each equally in God’s hands. For every man, all time is borrowed.

More days drifted by as we resisted accepting the unacceptable. We consulted magisterial documents related to end-of-life issues, prayed like never before, and discussed the matter with the chaplain, a faithful young priest named Fr. John. Upon meeting, Father and I recognized each other but neither could place from where. I mentioned this to Chris, who chided my memory lapse. I had indeed met Fr. John before: He’d witnessed Chris’s and his wife’s marriage vows nine years before.

Meeting our 4-year-old for the first time, Fr. John reached into his valise and said, "Mariclare, I’ve been wondering who to give this to, and now I know," as he handed her a lovely rosewood rosary that had been blessed by Pope John Paul in Paris. Its central bead was a round silver image of a monk. I took a closer look. Padre Pio’s grinning face looked back.

Having been told Naomi would soon be going to heaven, we asked Mariclare if she had any questions about anything at all. She looked at Fr. John and gave us a much-needed toddler moment. "Yes," she said without guile. "Will Jesus be able to juggle Naomi with all the other babies?"

An Angel to Charm the Archangels

We picked the Feast of the Archangels, September 29. Her death would also fall on a Friday. Each family member kissed her good-bye, and Fr. John administered the Anointing of the Sick for a last strengthening.

Providentially, a no-nonsense Catholic nurse named Katy was on duty that morning. At our request, Katy began the tube disconnections at noon, mirroring the start of Our Lord’s crucifixion. As she was freed at last from the bed, facial tape, and sundry tubes, we drank in Naomi’s delicate beauty for the first, last, and only time. Extra doses of pain medication were introduced and for the next two hours Mariella and I gently passed her back and forth between us, covered her with kisses, whisper-sang "Twinkle Twinkle Little Star," and wet her hair with our tears.

But those moments had none of the previous qualities of angst and depression. On the contrary, we felt quite carried along by many peoples’ prayers, and we knew with the certainty of faith that Our Lord would soon take Naomi from our arms to His. Her room took on the aspect of a sacred chapel. Most people enter the kingdom of God as babies; very few get three sacraments en route to glory as Naomi did in her 15 days on earth. St. Thomas Aquinas taught that the suffering of innocents, along with death itself, comprises the greatest obstacle to belief in God. Naomi manifested both. Is it not by looking to the innocent Christ suffering and dying on the Cross that we can "resolve" that terrible mystery by continuing to trust?

Naomi’s little life continues to have a big impact. We pray to her constantly. Trials like losing a child can bring untold blessings and a new tolerance for the "small things" that used to loom so important. My father coined the phrase "Naomi strikes again" to indicate a prayer answered or a grace received. She’s brought deeper bonds between family members, healing of lapsed friendships, new wonderment at the power of intercessory prayer, and a visceral appreciation for life’s fragility. Paradoxically, our inner selves feel more solid.

St. Faustina once wrote: "Receive into the abode of Your Most Compassionate Heart all meek and humble souls and the souls of little children. These souls send all heaven into ecstasy and they are the heavenly Father’s favorites." In that spirit, our family recommends asking mighty Naomi to put in a good word.

For being juggled by Jesus has its privileges.

This article originally appeared in the Jan/Feb 2007 Issue of Lay Witness Magazine

You Might Also Like

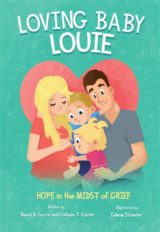

Some take a lifetime to fulfill their purpose. Others, such as babies who die prematurely, need much less time to accomplish God’s plan for their lives. Authors David and Colleen Currie share the story of their tenth grandchild, Louis Gerard, to offer hope to families suffering the loss of an infant and to assist children in the grieving process. Loving Baby Louie is a poignant story that will help small children understand the loss of a sibling and the eternal life that awaits them in Heaven.