A Conversation with Fr. Arne Panula by Mary Eberstadt

Note: Author Mary Eberstadt spent many hours conversing with Fr. Arne Panula in the months and weeks leading up to his death. Here, they talk together with clarity about our need not only for a relationship with God, but also a relationship with the Church.

Mary Eberstadt: What’s the importance of going to church, as opposed to “just being spiritual”?

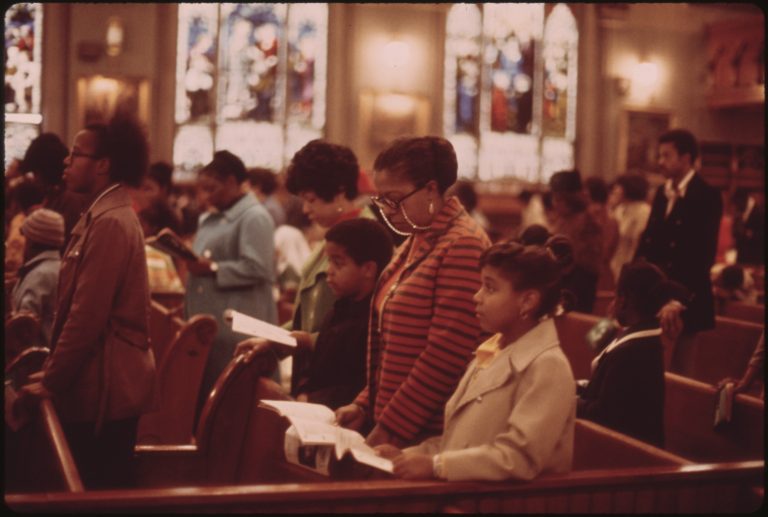

Fr. Arne: When people talk about being “spiritual” as opposed to religious, they’re talking about their personal experience of God—period. But God created us as social animals. We need to be connected to one another. The early Christian community, on being told to celebrate the Eucharist in memory of Jesus, developed rituals. These were practiced in community. There’s a great book by Brant Pitre called Jesus and the Jewish Roots of the Eucharist, showing how Mass developed out of the Sabbath. And there is also St. John Paul II’s wonderful 1998 Apostolic Letter—Dies Domini (The Day of the Lord): On Keeping the Lord’s Day Holy, which draws a thread through the Day of Creation, to the Day of Redemption in Christ, to the Day of the Church, to the Day of Eternity.

The idea that there’s a special day to rest, worship, be with family and in community, isn’t just some arbitrary quirk; it conforms to human nature—it’s something that human beings repeatedly reveal themselves to want. Similarly, the whole idea of the Liturgy of the Word is drawn from Jewish tradition.

We don’t exist as social isolates, but as beings who live in community and who practice things that only make sense in community. Worship is one of them.

Mary Eberstadt: In his History of Christianity, twentieth-century Yale historian Kenneth Scott Latourette makes a similar point about community. He asks how the faith could possibly have spread in just a few hundred years from a handful of bedraggled followers into a religion that would spread as far as Central Asia, India and Ceylon, north to Ireland, and the rest of the map of its flourishing.

Some assume the answer is that Emperor Constantine adopted the faith, and everyone else fell into line. But as Latourette points out, that can’t be so; Christianity had already spread across the Roman Empire without political help, indeed, despite centuries of persecution by the state itself.

Latourette argues instead that Christianity delivered what people were looking for better than its rivals did. In particular, its strict moral code set the religion apart, and gave people a stringent standard to which to aspire; and its extraordinary degree of fellowship made it stand out. This was manifest not only in the martyrs who went peacefully to their deaths, certain of their places in the Christian community; but also of the traditions established early on for taking care of the sick, the weak, the aged, the helpless.

The bottom line would appear to be: no community, no Christianity.

Fr. Arne: We aren’t meant to be atomized creatures. We want to share our beliefs, our feelings, our thoughts, our hopes. This is especially true of our deepest, most cherished convictions— our beliefs about what’s most important.

Being in St. Peter’s Square, whether for Mass or anything else, is so very different from hearing the Beatles in Central Park. Both are obviously venues for large numbers of people, united by something. But in St. Peter’s Square, what’s uniting people is a hub; and not just any hub, but one that transcends the merely human. When people feel transcendence, they want to share it with others; they want to be with others.

I like to compare the faith to a game of galactic tag. Someone who’s “it” touches another, and then the other has “it” too, and goes on to touch others. You can’t play tag alone.

Mary Eberstadt: Ludwig Wittgenstein observed that there can be no such thing as a private language, because language requires community—even presupposes it. The very idea of “private” religion seems logically impossible as well.

Fr. Arne: This is why the popular notion of being “just spiritual” is ultimately unsustainable. Yet still, Millennials especially are drawn to it—in part because atomization is so characteristic of their age.

I was just reading a reflection by Peter Lawler in Public Discourse, meditating thirty years later on Allan Bloom’s thesis in Closing of the American Mind. He’s illuminating on exactly this point about the atomization of today’s world, especially among the young, and how unnatural it is.

Lawler uses the phrase “social solitaries” to describe the children of today’s secularized elite—the next generation from the one described by Bloom. He writes: “They think of themselves as self-sufficient wholes. How can an individual be a whole? Only by being without the longing for relational love and by being unmoved by the invincible fact of personal extinction.”

That nails it, I think.

For her latest book, The Last Homily, noted author and speaker Mary Eberstadt spoke with the late Fr. Arne Panula of Washington, DC’s fabled Catholic Information Center. Her conversations with the beloved spiritual father range from sweeping discussions of art, history, and theology to everyday challenges like finding your vocation and thriving as a Catholic in a hostile culture.