The Adoration of the Magi

By Madeleine Stebbins [social-share]

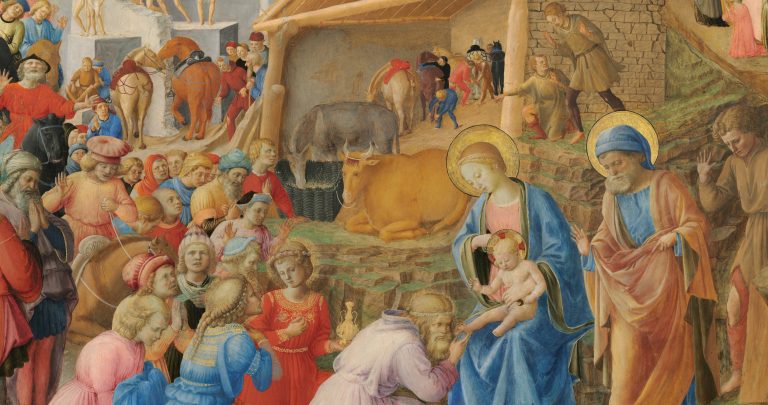

[caption id="attachment_139650" align="aligncenter" width="768"] The Adoration of the Magi (1440, 1460), Fra Angelico, completed by Filippo Lippi, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., United States[/caption]

The Adoration of the Magi was begun by Blessed Fra Angelico, a Dominican friar, and later completed by Fra Filippo Lippi. T seems that the Virgin Mary and the Christ Child (painted with particular delicacy and tenderness), the carpet of exquisite plants in the foreground, and the throng of worshippers in the upper right, as well as the architecture behind them, were painted by Fra Angelico. The rest—in a more robust, exuberant, and full-blown Renaissance style—is by Fra Filippo.

The architecture in the upper-right corner, along with the worshippers streaming down from and up toward a kind of heavenly Jerusalem, has a clarity of style that speaks a Dominican language of luminous spirituality. It is a saint’s sublime vision of beatitude.

This whole painting is a vision of grace emanating from the Incarnation, Nativity, and Epiphany of the Savior of mankind. Never has earth seen such an apparition of shimmering beauty. The goodness of the Lord has appeared. It is the unity and splendor of truth, beauty, and goodness. As Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger wrote, “Thomas Aquinas could say: The new law is the grace of the Holy Spirit (Summa Theologica I-II). Forms of worship and juridical orders . . . recede in importance, and what is truly universal emerges—grace, which is love poured out into our hearts by the Holy Spirit (Rom 5:5).

The clear brilliance of colors here expresses festive jubilation and joy. “Joy is a dilation and an exaltation of the soul,” writes Lacordaire. This painting is specifically about the Epiphany, which means “a manifestation.” The Magi are truly wise men. Their hearts were searching. They saw the star and are now kneeling in adoration of the Christ-child. They represent the Gentiles, who are also called to salvation, and so open up the Incarnation of the Savior to all. Here we see for the first time that the light of Christ is revealed not only to Israel, but to all nations, who eagerly approach the Redeemer with astonishment and wonder. Catholicity—that is, “universality”—means Christianity for all peoples. The joy that is a result of the good tidings has now burst upon the whole world.

There are many meaningful details in this painting. The white buildings are ruined yet noble: Christ has come to heal what is broken. The figures of pagans in the ruins have human dignity, and they watch in amazement. The humble beasts, which are part of God’s creation, serve and fit into His saving plan. The peacocks represent immortality: “For this I was born,” to bring everlasting life (John 18:37). The Virgin Mary is a throne (a seat of wisdom) on which sits the newborn King.

The Adoration of the Magi (1440, 1460), Fra Angelico, completed by Filippo Lippi, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., United States[/caption]

The Adoration of the Magi was begun by Blessed Fra Angelico, a Dominican friar, and later completed by Fra Filippo Lippi. T seems that the Virgin Mary and the Christ Child (painted with particular delicacy and tenderness), the carpet of exquisite plants in the foreground, and the throng of worshippers in the upper right, as well as the architecture behind them, were painted by Fra Angelico. The rest—in a more robust, exuberant, and full-blown Renaissance style—is by Fra Filippo.

The architecture in the upper-right corner, along with the worshippers streaming down from and up toward a kind of heavenly Jerusalem, has a clarity of style that speaks a Dominican language of luminous spirituality. It is a saint’s sublime vision of beatitude.

This whole painting is a vision of grace emanating from the Incarnation, Nativity, and Epiphany of the Savior of mankind. Never has earth seen such an apparition of shimmering beauty. The goodness of the Lord has appeared. It is the unity and splendor of truth, beauty, and goodness. As Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger wrote, “Thomas Aquinas could say: The new law is the grace of the Holy Spirit (Summa Theologica I-II). Forms of worship and juridical orders . . . recede in importance, and what is truly universal emerges—grace, which is love poured out into our hearts by the Holy Spirit (Rom 5:5).

The clear brilliance of colors here expresses festive jubilation and joy. “Joy is a dilation and an exaltation of the soul,” writes Lacordaire. This painting is specifically about the Epiphany, which means “a manifestation.” The Magi are truly wise men. Their hearts were searching. They saw the star and are now kneeling in adoration of the Christ-child. They represent the Gentiles, who are also called to salvation, and so open up the Incarnation of the Savior to all. Here we see for the first time that the light of Christ is revealed not only to Israel, but to all nations, who eagerly approach the Redeemer with astonishment and wonder. Catholicity—that is, “universality”—means Christianity for all peoples. The joy that is a result of the good tidings has now burst upon the whole world.

There are many meaningful details in this painting. The white buildings are ruined yet noble: Christ has come to heal what is broken. The figures of pagans in the ruins have human dignity, and they watch in amazement. The humble beasts, which are part of God’s creation, serve and fit into His saving plan. The peacocks represent immortality: “For this I was born,” to bring everlasting life (John 18:37). The Virgin Mary is a throne (a seat of wisdom) on which sits the newborn King.

This painting perfectly expresses the words of the prophet Isaiah: “Rise up in splendor, O Jerusalem! / Your light has come, / The glory of the Lord shines upon you. / Nations shall walk by your light, / And kings by your shining radiance. / Then you shall be radiant at what you see, / Your heart shall throb and overflow. (60: 1, 3, 5, Douay-Rheims)Madeleine Stebbins is the author of Looking at a Masterpiece and Let's Look at a Masterpiece: Classic Art to Cherish with a Child. These poignant works bring timeless truths to life through the beauty of art.