Although now known as one of the Church's wisest theologians, to his fellow seminarians Thomas Aquinas was the "Dumb Ox." And, despite his incredible intellect, Aquinas allowed his classmates to believe he was as unintelligent as he seemed.

This profound humility reveals the key to Aquinas' theology.

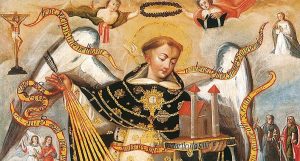

Over time, Aquinas earned another title: the Angelic Doctor. It reflected his reputation for more-than-human wisdom. According to the theology of Aquinas, his wisdom was obtained through human reason guided by grace and the promptings of the Holy Spirit. Grace, with its several categories, is a free gift from God that perfects nature. Aquinas held that his writings were the product of grace working on his own intellect.

Knowing his intellect depended on the grace of God, Aquinas claimed no fame for himself. He accepted the name Dumb Ox without objection.

Now we can see that his teacher St. Albert was right in saying, "We call this man the dumb ox, but his bellowing in doctrine will one day resound throughout the world."

The Relationship Between Grace, the Intellect, and the Will

An excerpt from The Love of God Poured Out: Grace and the Gifts of the Holy Spirit in St. Thomas Aquinas

by John M. Meinert

Actual grace is called cooperative in relation to an exterior act of the will, since an exterior act depends on actual grace, but not uniquely; it also depends on habitual grace and the interior act that preceded it and excites it. Actual grace is cooperative when it operates with free will to produce another salvific human act.78 Cooperative grace “is conferred for good works in which our will is not only moved, but moves itself, that is, when, already actually willing the final supernatural end, it converts itself to willing the means conducive to the end.”79 In other words, operative actual grace is the motion of God that causes humans to make their first act of human salvation, the first thinking and willing of salvation.80 Cooperative grace is thus said with respect to all acts that follow the first, the execution of the salvific understanding and willing. This is akin to the concurrence of God on the natural level, which is operative in regard to the first understanding and willing of the end and cooperative for all actions that pursue that end. More strictly speaking, as stated earlier, after the infusion of habitual grace, God’s graced motion (actual grace) can become cooperative. Prior to the infusion of habitual grace, the will’s indisposition prevents this. Actual operative grace prior to justification does give rise to activity, but it is not rightly called cooperative.

Although the primary act operative actual grace elicits is the first willing of salvation, it is not only for this purpose: it stands at the beginning of any new autonomous series of salvific actions in the supernatural life.81 Actual grace is operative in relation to the first interior act of a series, since nothing on the soul’s part could precede it.82 This interior act depends wholly on operative actual grace.83 “Hence it is not to be wondered at that, in this act wherein the will cannot move itself by virtue of a previous efficacious act of the same order, it should be referred to as moved only, and the operation attributed to God.”84 This obtains in three ways: the mode of contrariety (that is, the human begins to will the good when he previously willed evil), the mode of division within the same line of salvation (increases by exciting new acts in proportion to grace), or by the mode of simple interruption (“whenever [someone] is moved without counsel and a previous motive to the good”85).

[Bernard] Lonergan, although he agrees with the above analysis, goes into more depth. Before putting forth his own opinion, he rejects previous exegetical failures.86 In his positive exegesis, he offers five possible positions on the relation between operative and cooperative grace and the interior/exterior act.87 In the end, he commits to the third possibility: “The internal act of the will is with respect to the end; the external act is not merely the bodily execution but also the act of the will commanding this execution.”88 Hence, he agrees with many of his deceased interlocutors that the interior act “seems demonstrably to be the will of the end effected by the Eudemian first mover.”89 In this act, God moves operatively and there is no self-movement on the part of the soul. In the exterior act, the actual grace by which God operatively moved the soul to the end cooperates with the will in the choice of the means and bodily execution. More particularly, the exterior cooperative acts are the “internal acts of faith, servile fear, and hope.”90

- Ramírez, De Gratia, 697.

- Ramírez, De Gratia, 172.

- Ramírez, De Gratia, 695: “The first thought and first will of salvation.”

- Ramírez, De Gratia, 696.

- There is another disagreement here among the authors. Wawrykow claims that every supernatural interior act is the effect of operative grace (God’s Grace, 176). Garrigou-Lagrange (with whom Ramírez agrees) claims that only the first in a series is the effect of operative grace. Hence, an act could be interior and not an effect of operative grace. Rather it would be the effect of cooperative grace (Grace, 172: “This act is said to be external, although it may be only internal, since it is commanded by the will in virtue of a previous efficacious act of the same order”). Although Lagrange does not say here what he is taking the interior or exterior act to be, it seems most likely he is identifying them with the elicited/commanded distinction.

- Labourdette, Cours, 1:812: “C’est moi que agis, bien entendu, mais je ne suis pas porte à cet acte, j’y suis porté par l’influence de la seule grâce.”

- Garrigou-Lagrange, Grace, 170.

- Ramírez, De Gratia, 697. Ramírez here cites Cajetan for both the mode of division and the mode of simple interruption: “By the name of the first act (in this place) is not understood only that which the will has in the beginning of all its acts, but whenever it is moved to the good without counsel and a previous [act].”

- Lonergan, Grace and Freedom, 133ff.

- Lonergan, Grace and Freedom, 137: The difficulty of the passage would seem to be this: it gives a duplex actus, one internal to the will and one external; but the theory of the will gives a triplex actus: willing of the end, choice of the means, and bodily execution. If we denote the pair by A and B and the trio by X, Y, and Z, respectively, then the possible interpretations may be listed as follows: (1) A is X, and B is Y; (2) A is X, and B is Z; (3) A is X and B includes both Y and Z; (4) A includes both X and Y, and B is Z; (5) A is Y, and B is Z.

- Lonergan, Grace and Freedom, 140.

- Lonergan, Grace and Freedom, 139.

- Lonergan, Grace and Freedom, 142