An excerpt of our FREE online Bible Study

Course Description

The drama in the Gospels turns on a single question: Is Jesus the long awaited Messiah, the son of David come to restore the everlasting monarchy promised to David? Underlying this drama are centuries of rival interpretations of the Jewish Scriptures and competing expectations of who the Messiah was to be, the signs that would accompany his coming, and the shape of the kingdom he would establish.

We explore all these issues in this thematic survey course, which goes to the heart of what the New Testament has to say about the identity of Christ and the Church.

D. The Prime Minister

The Twelve thus took their positions as the King’s ministers. Just as David and his successors had had ministers to sit on thrones and judge the people (see, for example, 1 Kings 4:1-19, and compare Psalm 122:4-5), so Jesus, the ideal Davidic King, would have His ministers.

And just as in the original Davidic kingdom, one of those ministers would be the leader of the rest.

David had Joab (see 1 Chronicles 11:6), and every one of his successors had what we today would call a prime minister.

Following that pattern, we see that Jesus, too, had a prime minister.

As soon as He told His disciples that they would sit on thrones to judge the twelve tribes of Israel (see Luke 22:28-30), Jesus turned to Simon Peter and told him that he must strengthen the others (see Luke 22:31-32).

Peter was the “Rock” (which is what the name Peter means) on which Jesus had promised to build His Church (see Matthew 16:18).

All the Apostles were Jesus’ ministers, but Simon Peter was the prime minister.

Now we see Peter exercising that authority. It is Peter who announces to the Twelve and the rest of the church in Jerusalem that Judas must be replaced (see Acts 1:15-22), and his decision is accepted without debate (see Acts 1:23-28).

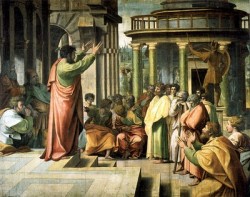

We see him acting as the unquestioned leader at Pentecost, too, when he speaks for all the Apostles in front of the astonished crowds (see Acts 2:14).

Peter speaks for them again before the leaders of the people and the priests (see Acts 4:8). He exercises a healing power like Christ’s (see Acts 3:1-12), pronounces God’s judgment on Anananias and Sapphira (see Acts 5:1-11), and gains such a reputation that people line up just to be touched by his shadow (see Acts 5:15).

Finally, it is Peter whose word determines the whole future course of the Kingdom on earth. When some converted Pharisees have argued that Christians are bound by the whole law (see Acts 15:5), Peter is the one who interprets the will of God for the rest of the Apostles (see Acts 15:7-11).

James, summarizing the decision of the Apostles, refers to Amos’s prophecy about the fallen hut, in which the restoration of the Davidic kingdom comes about so that the rest of the world may also come to God (see Acts 15:14-18).

A kingdom that includes “the rest of humanity” is what God had promised through the Prophets, and the mission of the Church is to be the fulfillment of that promise.

Luke leaves us in no doubt whatsoever: Peter has taken over as leader of the Twelve, just as Jesus had ordained. He interprets the will of God, and he decides the course of the whole Church.

But Peter is only the first among the ministers of the Kingdom. Jesus, as Peter himself will tell us, is still the King.