By Louis St. Hilaire

Louis St. Hilaire is the author of That You Might Have Life: An Introduction to the Paschal Mystery of Christ and translator of The Literal Exposition of Isaiah: A Commentary by St. Thomas Aquinas (forthcoming from Emmaus Academic). A graduate of Franciscan University of Steubenville, he works as a web developer and digital editor for the St. Paul Center.

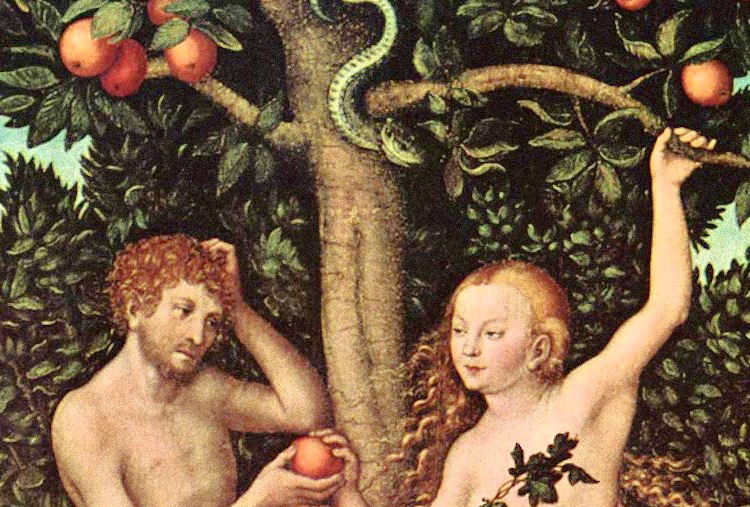

The original holiness and harmony of our first parents in the Garden of Eden that we read about in Genesis 2 is quite different from the life we know today. Genesis 3 explains how human beings lost this original state through sin.

Like the story of creation told in the first two chapters of Genesis, the story of the fall in Genesis 3 uses poetic and symbolic language. This doesn’t mean that the story of the fall is just a myth, with no relationship to history or reality. The fundamental things about which it teaches us really did happen: our first parents were created in friendship with God, they did lose that friendship through sin, and profound consequences for the entire human race, which descends from them, did follow. However, just as with the first two chapters of Genesis, we don’t read Genesis 3 like a news report or a history textbook. Instead, we have to examine the figurative language in Genesis 3 to see how it reveals the theological significance of these events.

God had warned Adam and Eve that if they were to eat of the fruit of the tree, they would die (Gen 2:17; 3:3). This wasn’t simply a threat or a way of intimidating them, but a statement of the true consequences of choosing something other than God.

Sure enough, as soon as Adam and Eve made the choice to disobey God, we immediately see a dramatic change in them. They didn’t drop dead on the spot. Physical death didn’t come immediately (although that, too, came in time). Instead, they experienced spiritual death. They lost their original holiness and justice. They lost the sanctifying grace—the life of God—that animated their souls. Then, having lost the harmony of original justice within themselves and between each other, they were suddenly ashamed of their nakedness (Gen 3:7). Having broken their friendship with God and believing Satan’s lies about him, they ran and hid from him (Gen 3:8). After that, when questioned by God, they pointed fingers at each other instead of taking responsibility for their bad choice (Gen 3:9–12).

God, witnessing all this, foretold that their lives would now be marked by suffering, toil, and, finally, death (Gen 3:16–19). Likewise, because they could not abide by the limits set on them as creatures, they had to leave the garden (Gen 3:22–24). Thus, because of sin, suffering, and death enter human history, and in the following chapters of Genesis, we see the consequences of sin spread throughout the world (CCC 399–401).

This is the world into which we are born—a world of suffering, sin, strife, and death. The sin of our first parents affects us all, and we can’t understand our suffering or our tendency to evil apart from this sin (CCC 403). We call the sin of our first parents and the resulting fallen state of human nature that affects every human person “original sin.”

This raises an important question: How can it be that everyone, even today, is affected by a sin committed by someone else long ago?

In order to understand the answer to this question, we first need to see that when Genesis tells us that all human beings are descended from a single couple, it teaches us a lesson about the profound unity of the human race. Today, we live in a society that is radically individualistic. It encourages us to see people as isolated individuals who are only responsible for themselves and their actions. But that’s not how God made us. He made us as members of closely interconnected communities, where responsibility is shared and the actions of a single person can affect everyone else dramatically. Because the human race is united in this way, when Adam and Eve lost the gifts of original holiness and justice, the entire human race lost them. The human nature that we receive from them as their descendants is deprived of these gifts. St. Paul, reflecting on this, says, “as sin came into the world through one man and death through sin, and so death spread to all men because all men sinned” (Rom 5:12; CCC 404).

That being said, original sin is not “sin” in the sense of a personal sin for which we are guilty. Rather, it refers to this deprived or fallen state. Our nature is not completely corrupted, but it is wounded. We are affected by ignorance, suffering, fear of death, and an inclination toward sin called “concupiscence.” This in turn leads to personal sins, for which we are culpable. In this way, sin affects us as individuals and as a society, distorting human social structures, and making us subject in many ways to the power of Satan (CCC 405–408).

In a sense, original sin is the “bad news”: it explains why we are separated from God, why we tend to do what is wrong even when we know better, and why we suffer from conflict, unhappiness, and death. Because of original sin, human life is a battle. We were created in the image of God and meant to enjoy life with him, so we have within us a deep desire for the holiness and justice we lost. At the same time, we are afflicted by sin, its effects, and the power of Satan. As a result, our life is a struggle between competing desires, and we can’t overcome that struggle on our own (CCC 409).

Fortunately, God doesn’t expect that of us. No sooner did man fall than did God promise to send a savior to rescue us, telling the serpent: “I will put enmity between you and the woman, and between your seed and her seed; he shall bruise your head, and you shall bruise his heel.” (Gen 3:15)

In these words, the Church recognizes the first promise of the Savior, Jesus, the descendant of Adam and Eve who would free us from the power of Satan (CCC 410).

You Might Also Like

The Formed in Christ series is a solid and faithful resource that provides a thorough treatment of the Catholic faith and the various branches of theology. That You Might Have Life: An Introduction to the Paschal Mystery of Christ takes us through creation, the Fall of Man, and Christ’s Paschal Mystery to the reader’s own life and what Christ’s redemption means for us.