By +Father Ray Ryland, Ph.D., J.D.

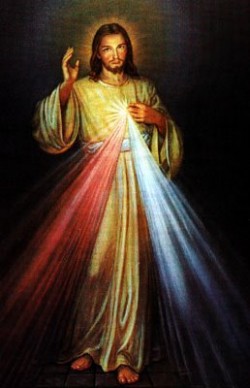

Pope John Paul the Great gave us Divine Mercy Sunday.

Over a period of thirty-five years, from the time when he was archbishop of Krakow, John Paul actively forwarded the process of canonizing Sister Faustina.

On April 30, 2000, the first Sunday after Easter, John Paul canonized Sister Faustina—now SaintFaustina. In his homily of canonization, John Paul joyfully announced that the first Sunday after Easter “from now on throughout the Church will be called ‘Divine Mercy Sunday.’”

Throughout Scripture and our liturgy we hear about divine mercy; so often, in fact, that we may be tempted to take it for granted. That would be a grievous error. Think with me for a few moments about divine mercy.

Hundreds of times and in many ways throughout Sacred Scripture, the text exults in the mercy of God. We read, for example, that the mercy of God is “great” (1 Kings 3:6); “plenteous” (Ps 86:5); “tender” (Lk 1:78) “abundant” (1 Pet 1:3); it is “from everlasting to everlasting upon them that fear him” (Ps 103:17).

In the legal form, mercy is the opposite of justice. Justice is what a person deserves. Mercy is what a guilty person needs.

In His mercy, God reveals that love always trumps justice. Indeed, in his encyclical Rich in Mercy, Pope John Paul II declared that mercy is “love’s second name.”

So far as our individual relationships with God are concerned, mercy is God’s greatest attribute and perfection. Because human history is a history of sin and death, God’s love has to be revealed and made real in human lives primarily as mercy.

Rich in Mercy

In his book The Devil’s Dictionary, a humorist of last century defined mercy as “an attribute beloved of detected offenders.” Though the man was speaking cynically, he was also speaking the truth. All of us are offenders against God, and all of us have been detected.

So the “true and proper meaning of mercy,” Pope John Paul told us, is God’s love drawing “good from all the forms of evil existing in the world and in man.” We have to say, therefore, that mercy is (in John Paul’s words), “the fundamental content of the messianic message of Christ. . . .” It is, in fact, the basic power of His mission on earth (Rich in Mercy, no. 6).

To bring the meaning of mercy into ultimate focus, we must say that Jesus Christ incarnates mercy; indeed, Jesus Christ is mercy (Rich in Mercy, no. 2).

Our salvation hinges on trusting in God’s mercy. But remember: Mercy means pardon forguilt. Pardon for our guilt can come, by God’s mercy, only if (a) we face and acknowledge our guilt under God, and (b) we are truly sorry for having offended God.

God will not, God cannot, fill with His mercy the life of one who is not truly penitent. Jesus made this clear with His parable of the prayers of the Pharisee and the tax collector. Recall that the Pharisee congratulated God and himself on his own good character. In sharp contrast, the tax collector simply groaned, “God, be merciful to me a sinner!” Jesus said that only the tax collector was reconciled to God.

A Lost Sense of Sin

When we think about God’s mercy, therefore, we have to ask ourselves about our own sense of sin. And that’s our second point.

Start with the fact that our culture has lost any real sense of sin. In all of human history, there apparently has never been a society that so widely ignored—or even widely denied—the reality of sin as our culture.

We read in the Old Testament that even pagan rulers like Nebuchadnezzar or the king of Nineveh acknowledged their sins and repented of them. In every primitive society of which we have any information, one always finds a sense of sin, even though pagan beliefs about their gods may be highly superstitious.

Back in the 1940s, in a radio address to an American catechetical conference, Pope Pius XII stated that “the sin of the century is the loss of sin.” In the later 1950s, he declared that the most serious spiritual problem of Catholics is the loss of a sense of sin. Pope John Paul also strongly emphasized the same fact.

That we Catholics have largely lost a proper sense of sin is quite clear, for two reasons: Only a very small percentage of otherwise practicing Catholics regularly choose to receive the Sacrament of Penance. Furthermore, many—should I say most?—Catholics who do go to Confession seem to find it hard to be specific in their confessions.

The fact is, our consciences have become calloused. Our consciences have been calloused by the moral and doctrinal confusion created by dissenters, unfaithful Catholics who reject the Church’s authority. Our consciences are continually being calloused by the moral filth that flows from the media: from our TVs, from our movies, from the books and magazines we read, from the newspapers. In 1982 Pope John Paul warned us that “modern man is threatened by an eclipse of conscience . . . a deformation of conscience . . . a numbness or ‘deadening’ of conscience” (Reconciliation and Penance, no. 18).

Not Just for Mortal Sins

The common Catholic rationalization for not going to Confession—if people bother to rationalize—is usually, “well, I don’t have any mortal sins to confess.”

Let me remind you that the Sacrament of Penance was given by our Lord Jesus Christ not only for mortal sins, but also for venial sins. Let me remind you further of our Catechism’s listing of the very harmful effects of venial sin.

Venial sin weakens charity; it manifests a disordered affection for created goods; it impedes the soul’s progress in the exercise of the virtues and the practice of the moral good; it merits temporal punishment. Deliberate and unrepented venial sin disposes us little by little to commit mortal sin. (no. 1863)

How dare we take venial sins lightly?

Ponder carefully what Pope John Paul the Great taught us in apostolic exhortation entitledReconciliation and Penance.

As a rupture with God, sin is an act of disobedience by a creature who rejects, at least implicitly, the very one from whom he came and who sustains him in life. It is therefore a suicidal act” (emphasis added). And why is that? Because by refusing “to submit to God, . . . [the sinner’s] internal balance is also destroyed” and “contradictions and conflicts arise” within himself.

In the next section of the exhortation, the Holy Father becomes more specific in his teaching. “By virtue of human solidarity which is as mysterious and intangible as it is real and concrete, each individual’s sin in some way affects others.” That is, “one can speak of a communion of sin, whereby a soul that lowers itself through sin drags down with itself the church and, in some way, the whole world.”

This, said the Holy Father, is the bedrock fact: “. . . there is no sin, not even the most intimate and secret one, the most strictly individual one, that exclusively concerns the person committing it. With greater or lesser violence, with greater or lesser harm, every sin has repercussions on the entire ecclesial body and the whole human family” (no. 16; emphasis added).

Loving Jesus

So if we want the mercy of God to flood our hearts—and who of us does not?—we have to work at deepening our sense of our own sin.

Consider the lives of the saints, who made such frequent use of the Sacrament of Penance. We regard their lives as exemplary. We wonder, what did they have to confess? Yet the fact is, they were all keenly conscious of a heavy weight of sin.

Why did the saints have such deep consciousness of sin? It was a reflection of their deep love for Jesus. The more intimately they knew and loved Him, the more painfully conscious they were of the ways in which they offended Him.

The point for us is, the deeper our love for Jesus, the more we will be aware of our sins and the greater will be our sorrow for the suffering our sins have inflicted on Jesus. And turn the proposition around. If we have slight sense of our own sinfulness, what does this tell us about the quality of our relationship with Jesus?

If we truly yearn to grow in sanctity—and that’s our whole reason for living—we need to go to Confession frequently. When we go to Confession frequently, we can make a more thorough confession, and thereby more deeply receive the mercy of God.

And I mean specific confession: none of this confession by title: “I was uncharitable” or “I was critical” or “I was unforgiving.” Be specific: call a spade a spade, or even call it a dirty old shovel. When you confess specific sins, you get them out in front of you and see them in all their ugliness: and you say to yourself, “And Jesus suffered agony for this!”

You and I need to make frequent aspirations in the course of a day. We need to call on the holy name of Jesus, or on the Blessed Trinity. We need to recall ourselves into the presence of the Blessed Trinity. We need to try consciously to carry out our responsibilities in such a way as to give honor and glory to God. We need to be nourished by regularly reading the Scriptures—especially the Gospels—and by doing spiritual reading.

Until we draw our last breath, we have to work at growing in our love for our Lord Jesus, growing in our basic desire to please Him in word and thought and deed.

When a sudden heart attack occurs, how thankful we are if someone present has been trained to practice CPR. That means someone who can keep blood carrying oxygen to the heart and brain of a person until that person’s heart begins to beat again.

Divine Mercy Sunday tells us about spiritual CPR which Our Lord entrusted to His Church. He gave to His bishops and priests the Sacrament of Penance, the authority to act in His name and forgive sins. This sacrament is spiritually life-giving.

Jesus gave us this sacrament not as a simple option, but as something He wants us to use.

When we ignore this sacrament, we ignore Jesus’ command given for our spiritual welfare. And when we ignore His command, we ignore Him.

God forbid that any of us should ever do that!

Ray Ryland was a priest of the Diocese of Steubenville and a spiritual director to many Catholic apostolates. His memoir, Drawn From Shadows into Truth, is available through Emmaus Road Publishing.