By Robert Nusca

Msgr. Robert Nusca is the author of The Christ of the Apocalypse: Contemplating the Faces of Jesus in the Book of Revelation, a book that offers insight into one of the most misunderstood books of Scripture by uncovering the presence of Our Lord within its pages.

The extraordinary images that fill the story world of the Apocalypse of John sparkle, simmer, and seethe with an electric, otherworldly glow that has helped to account for its perennial allure since it first appeared toward the end of the first century.

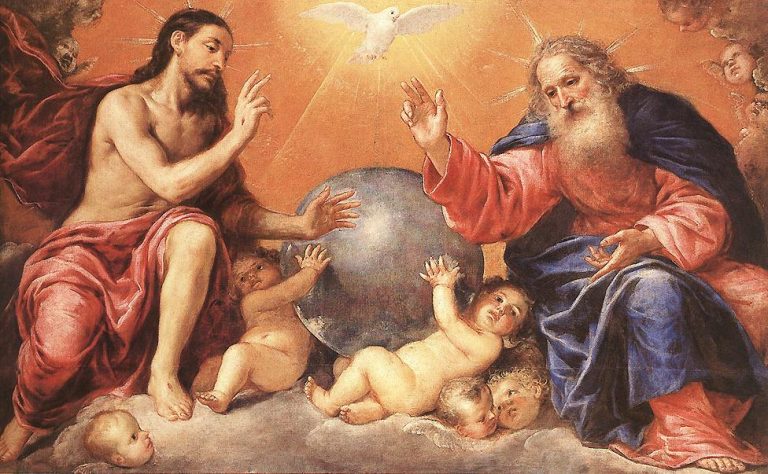

The Apocalypse certainly contains many haunting images of death and destruction on a cosmic scale, as the images of locusts, frogs, hail, earthquakes, and falling stars recall the plagues described in the Book of Exodus (and those reprised by the sage in the Wisdom of Solomon 11:2–19:22). In the narratives which focus on judgment, these plagues are unleashed by the Lamb before God’s throne (Rev 5:6), as He opens the mysterious scroll that is sealed with seven seals (beginning in 6:1). The book’s portrayal of the dark side in the battle between good and evil features a cast of infernal characters that includes the unholy trinity—or at least triad—of Satan (12:3ff.), the “beast rising out of the sea” (or “Antichrist” in 13:1), the “beast rising out of the earth” (or false prophet in 13:11), and the armies—both visible and invisible—that are allied with them. The story relates a succession of images that have captivated the imaginations of successive generations of readers, including: the Four Horsemen (6:2ff.), the Number of the Beast (13:18), the battle of Armageddon (16:16), the “lake of fire that burns with sulfur” (19:20, 20:10), the thousand-year reign (20:2–6), and the second death (20:14, 21:8) reserved for God’s enemies.

The basic facts about this Apocalypse (from which the literary genre of apocalypse takes its name) have too often gone unnoticed: That it is an Apocalypse of Jesus Christ (1:1), and that the story world is throughout a God- and Christ-centered one, and the Seer’s visions permit the reader to look with him through the open door to heaven (4:1ff.) onto a shimmering, celestial world that resounds with the songs of angels. Far beyond predictions of the end of the world, John invites the community that listens to his prophetic message not only to gaze in awe and wonder upon the world described beyond the opened door, but to enter with him through that door and to stand alongside the angels in the praise and worship of God and of the Lamb. While many powerful and captivating images emerge as the book’s narrative unfolds, the audience is presented with a rich and multi-faceted portrait of Jesus Christ, the Son of God, who stands—alongside God—at the very center of this enigmatic last book of the Bible.

The figure of Jesus Christ that emerges from among the many powerful apocalyptic visions described in Revelation’s story world is a complex and profoundly theological one that speaks directly to the life situation of John’s audience in late first-century Asia Minor. The book’s literary genre (apocalypse), its use of language, and the vast array of symbols that fill its story world are, admittedly, quite distinctive in contrast with the Gospels. Unlike the accounts of the appearances of the Risen Lord to the disciples handed down in the Gospels, Revelation’s images of Christ are the fruit of the author’s own Spirit-inspired apocalyptic visions and his theological reflection several decades after the events described by the evangelists. While the author writes as an early Christian prophet (22:6, 9) and understands his work to be a book of prophecy (1:3; 22:10, 18–19), his Apocalypse—just like the other writings of the New Testament—presents a coherent, theological reflection on the person and the mystery of Jesus Christ, the Son of God (Mark 1:1; Jn 20:31) to nourish the faith life of the communities of believers to whom his book is addressed (1:4).

Although John’s portrait of Christ is extraordinary in its apocalyptic tenor and tones, what he is striving to accomplish is entirely consistent with the aims of the other sacred writers of the New Testament. Indeed, from the Gospel of Matthew to the Book of Revelation, the New Testament contains a variety of portraits of Jesus Christ. They have been shaped by history and tradition by a variety of theological concerns and specific pastoral issues. They have been preserved and handed on by living communities of faith, guided by the refining fire of the Holy Spirit in prayer and worship. The Faces of Christ in the New Testament have succeeded in speaking through the centuries to the hearts of spiritual seekers in every age and have the power to continue to speak to us today.

You Might Also Like

That the Apocalypse of John is a “Revelation of Jesus Christ” (Rev 1:1) is a fact too often overlooked by interpreters of this last book of the Bible. As Msgr. A. Robert Nusca’s The Christ of the Apocalypse: Contemplating the Faces of Jesus in the Book of Revelation proposes, beyond predictions of earthquakes and falling stars, St. John articulates from start to finish a multifaceted and compelling portrait of Jesus Christ.