By Madeleine Stebbins

Madeleine Stebbins is the author of Looking at a Masterpiece and Let’s Look at a Masterpiece: Classic Art to Cherish with a Child. These poignant works bring timeless truths to life through the beauty of art.

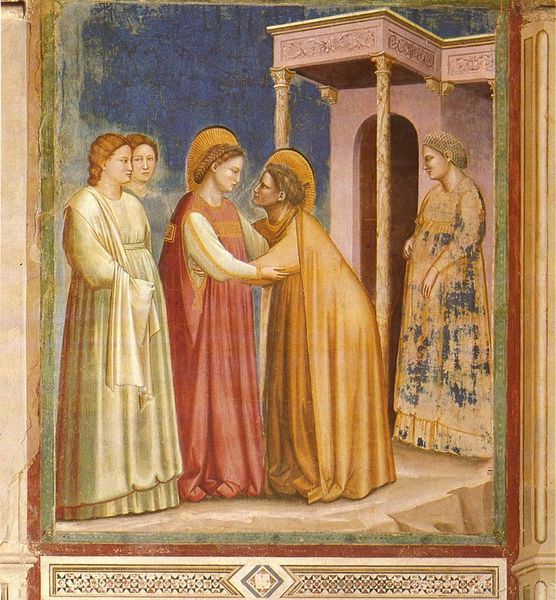

This fresco of the Visitation by Giotto speaks in the language of the Bible, specifically of the Gospels. In a few sparse words it tells us the essentials and carries within itself the content of divine Revelation. There are no ornaments or descriptions, no flamboyant gestures or rhetoric. Like Scripture, this fresco has an inspired simplicity. It gets to the heart of the event.

It is amazing how Giotto is able to say so much with such few means. He, the great painter of the life of St. Francis of Assisi, was a third order Franciscan. His style, in its poverty of means, is related to the Franciscan spirit of asceticism, tenderness, ardor, and unadorned naturalness.

Here are two pregnant women, Mary and Elizabeth. By a singular grace from the Holy Spirit, the unborn child John the Baptist first receives the revelation of the Messiah’s presence. He leaps in the womb, and through the intimate union of mother and child, “Elizabeth was filled with the Holy Spirit” and recognized “the mother of [her] Lord” (Luke 1:41, 43). Elizabeth receives this grace through the medium of her unborn child. If a pregnant woman is conscious night and day of the child under her heart, how immeasurably more is this so with the Blessed Mother, who carried God’s Son within her. We see in her an inner absorption, a contemplation of God, out of which pours forth her exultant Magnificat (Luke 1:46–55). She foretells that all generations shall call her blessed (Luke 1:48).

Mary is pictured in her regal role, solemnly aware that she is the Mother of God (Theotokos in Greek). Her expression suggests that she is profoundly moved and humbled by that fact, and she gives God the glory: “He who is mighty has done great things for me, and holy is his name.” She is queen, without pomp and circumstance, but with incomparable dignity and spiritual majesty. “She found her dignity and vocation not in power but in humility,” wrote Emily Stimpson. Mary’s posture conveys mercy.

Giotto’s genius condenses the drama of that moment into its fundamentals. Elizabeth recognizes Mary as “blessed . . . among women, and blessed is the fruit of [her] womb” (Luke 1:42). She looks up to Mary with devotion and wonderment. It is the model for the veneration (hyperdulia) that Catholic Christians have toward the Blessed Mother, which The Catechism of the Catholic Church says “differs essentially from . . . adoration” (971). In Mary’s face and in the unusual red color of the tunic (the liturgical color of the blood of martyrs) is a premonition of the suffering to come. The two women embrace, indicating their intimate bond and mutual support, serving each other.

The other women attendants, not yet fully let in on the great secret, stand outside the inner circle. This fresco gives us a powerful insight into the vocation and election of women. Great things are confided to women. They are called in a special way to be receptive vessels who spiritually carry the redemptive word in their hearts (see Luke 2:51), even as Mary also carried Him physically. It is a vocation to love and to spiritual motherhood. In The Privilege of Being a Woman, Alice von Hildebrand writes, “Women are actually granted a privileged position in the economy of redemption.” Their “mission traditionally has been to serve, following thereby Our Lord, who said, ‘I have not come to be served but to serve.’”

You Might Also Like

What power does great art have? In Looking at a Masterpiece, the reader will discover the surprising answer—that great art can “influence our whole lives.” As author Madeleine Stebbins explains, “Great art deepens the soul, inspiring a thirst for greatness and purifying it of what is base. It opens our minds to a clearer perception of truth and our imaginations to a more radiant vision of moral goodness and nobility.”

What power does great art have? In Looking at a Masterpiece, the reader will discover the surprising answer—that great art can “influence our whole lives.” As author Madeleine Stebbins explains, “Great art deepens the soul, inspiring a thirst for greatness and purifying it of what is base. It opens our minds to a clearer perception of truth and our imaginations to a more radiant vision of moral goodness and nobility.”