By Andrew Willard Jones and Louis St. Hilaire

Dr. Andrew Jones holds a PhD in Medieval History from Saint Louis University and is an expert on the Church of the High Middle Ages. He is the author of Before Church and State: A Study of Social Order in the Sacramental Kingdom of St. Louis IX and the pioneer of the Formed In Christ series of faith formation texts, as well as the author of several books in this series.

Louis St. Hilaire is the co-author of Evidence of Things Unseen: An Introduction to Fundamental Theology and translator of The Literal Exposition of Isaiah: A Commentary by St. Thomas Aquinas (forthcoming from Emmaus Academic). A graduate of Franciscan University of Steubenville, he works as a web developer and digital editor for the St. Paul Center.

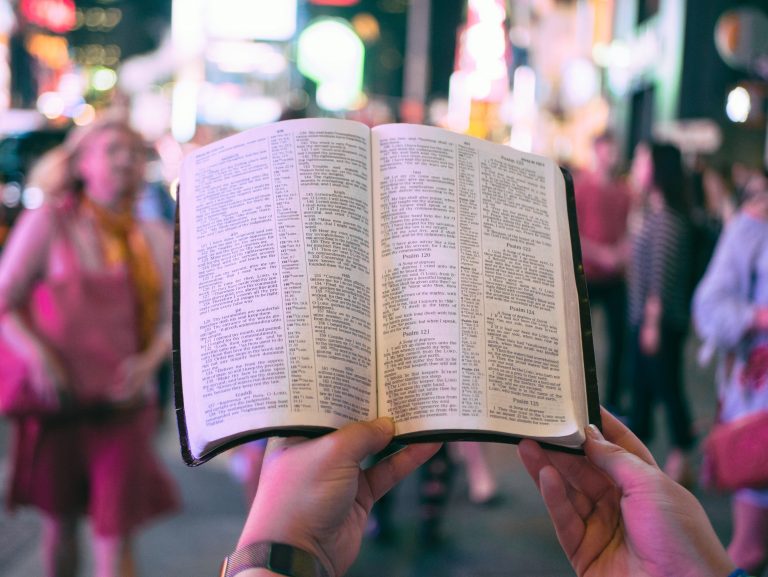

The Bible is unique. No other work of writing has ever been so studied, so commented on, so debated. It has been a part of the Church from the beginning, and each generation continues to grapple with it.

It is not one book among many; it’s the Book. Therefore, the Scriptures must be treated with the highest honor and respect. As we discussed in Part II, the Church believes the Bible always teaches the truth but it doesn’t always do that in a “scientific” way. The Bible is full of many different types of writing. It includes poetry and what we might call literature—fables and allegories—but this does not make it untrue. Inherent in the charge that the Bible is just literature and therefore not worthy of belief is the prejudice that the only truth possible is that gained through scientific investigation and scientific proofs. This is both untrue and an inhuman way of looking at the world.

Of course music, poetry, paintings, and novels are capable of communicating truth. The ability to make things and the ability to appreciate beauty are part of what it means to be a human being. So too is the ability to tell stories and understand the meaning of stories. We communicate truth to each other all the time through beauty—through novels and films, through operas and paintings, through poems and statues—and those truths are no less valid because they don’t come to us through the scientific communication of exact data. In the Scriptures, God speaks to us as human beings (he actually became human), and so he speaks truth to us using all of the means human beings use to communicate truth.

Accordingly, we need to approach these different modes of communicating in the way appropriate to them. In our daily lives, we would never listen to a song in the same way that we would read a research paper or study an accounting spreadsheet. The same holds true for the Bible. We need to read the Psalms differently than we read the Gospels. We need to read the opening chapters of Genesis differently than we read the Letters of St. Paul. Doing that actually makes it easier to perceive the truth being communicated by each.

With all that being said, it is remarkable the extent to which modern archaeology and history has confirmed the events of the Bible. Even after centuries of active attempts to disprove the biblical accounts of the history of Israel and the life of Christ, nothing has been found “scientifically” that significantly challenges our biblical understanding of what happened. In fact, the opposite is the case: most evidence supports the biblical narrative.

We need to remember that the Bible must be interpreted within the context of the literary type of each book, the historical and cultural context, and in continuity with the rest of Scripture. When we take this context into account, we discover the meaning that comes directly from the text and the intention of the inspired author, which is called the “literal sense” of Scripture. The literal sense is the basis for all other senses of Scripture. So in this sense the Scriptures can be understood as always having a true “literal” meaning. The Church, however, does not propose a fundamentalist approach to Scripture in which Scripture is understood as always being literally true in the sense of being simply true without the need of analysis or interpretation of context.

In short, the Church does not claim that the Bible always presents scientific or historical facts. Rather, the Bible’s purpose is to present truths about God and humanity. Nevertheless, many portions of the Bible are historically and factually true; for example: the Incarnation, Crucifixion, and Resurrection of Jesus. The contextual approach to interpreting Scripture will always give you the right perspective. The Church is aware of the difficulties attached to the interpretation of Scripture and has given guidelines for how it should be approached.

You Might Also Like

In his recent Apostolic letter Aperuit Illis, Pope Francis established the Third Sunday of Ordinary Time as the Sunday of the Word of God. As we celebrate the inaugural feast on January 26, find a few ways to follow Pope Francis’ call to make Scripture a part of everyday life throughout the new year.