By Scott Hahn

Dr. Scott Hahn is the best-selling author of over forty books, including Hope to Die: The Christian Meaning of Death and the Resurrection of the Body. He is the founder and president of the St. Paul Center and holds the Fr. Michael Scanlan Chair of Biblical Theology and the New Evangelization at Franciscan University.

On the last day of the feast, the great day, Jesus stood up and proclaimed, “If anyone thirst, let him come to me and drink. He who believes in me, as the scripture has said, ‘Out of his heart shall flow rivers of living water.’” Now this he said about the Spirit, which those who believed in him were to receive. —John 7:37-39

The line is worth repeating: “This he said about the Spirit, which those who believed in him were to receive.” Jesus issues his invitation to “anyone” who thirsts for salvation. To those who believe he promises salvation through the gift of the Spirit.

Thus he presents the gift of the Spirit as the culminating mystery of redemption. In the words of the Nicene Creed, Jesus “came down from heaven” “for our salvation.” And the Fathers understood salvation as the Christian’s share in divine life. In this passage from St. John’s Gospel, Jesus makes clear that divine life is given to us as the Holy Spirit.

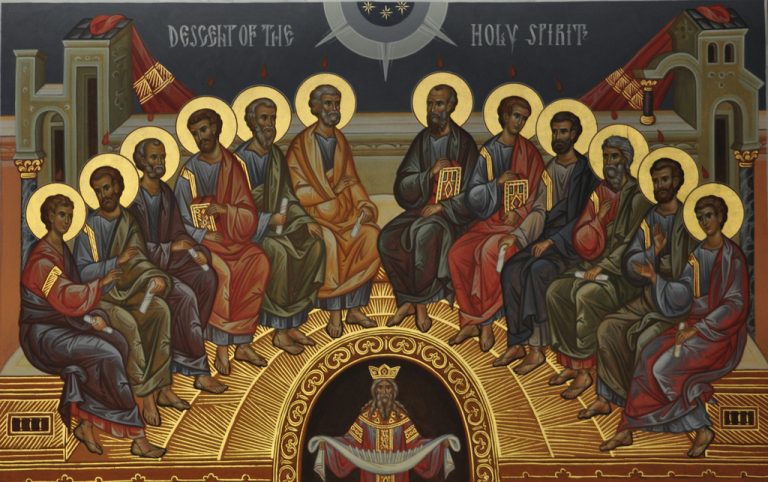

What is first in intention, then, is last in execution. The giving of the Holy Spirit is the reason for the Incarnation. Pentecost is the reason for Christmas and Good Friday and Easter and the Ascension. Throughout his earthly ministry, Jesus longed to light a fire upon the earth (Lk 12:49), and only on Pentecost—with the appearance of the Spirit as tongues of flame (Acts 2:3)—do we see that fire blazing.

It is only by the Spirit that we can know God: “For what person knows a man’s thoughts except the spirit of the man which is in him? So also no one comprehends the thoughts of God except the Spirit of God” (1 Cor 2:11). It is only by the Spirit that we can pray as children of God and not as slaves: “For you did not receive the spirit of slavery to fall back into fear, but you have received the spirit of sonship. When we cry, ‘Abba! Father!’” (Rom 8:15; see also Gal 4:6). It is in the Spirit that we live (Rom 8:9) and are baptized (1 Cor 6:11) and become a dwelling place for God (Eph 2:22). It is in the Spirit that God is revealed to us (Rev 1:10).

The scriptural testimony to the life and missions of the Holy Spirit is abundant. It is a wonder that the Council of Nicaea gave so little space to the Spirit in its final article. Indeed, less than a century afterward, St. Augustine complained, “Many books have been written by scholarly and spiritual men on the Father and the Son. . . . The Holy Spirit has, on the other hand, not yet been studied with as much care and by so many great and learned commentators.” And little has changed over seventeen centuries. Pope Francis remarked, quite recently, that “the Holy Spirit is unknown!” His immediate predecessor observed that “the Holy Spirit has largely remained the Unknown God.”

It is a circumstance we should want to remedy, even after millennia of precedent. Yet Cardinal Ratzinger helps us to understand, perhaps, why even a great creedmaking ecumenical council could come to exemplify this “neglect.” He notes that the Spirit—in all of Sacred Scripture—never testifies to the Spirit, but rather only to the Father and to the Son. Thus we know the Spirit only by the fire cast upon the earth. We know the Spirit by divine deeds. Cardinal Ratzinger concludes: “We can never know the Spirit otherwise than in what he accomplishes. This is why Scripture never describes the Spirit in himself. It tells us only how he comes to man and how he can be distinguished from other spirits.”

When the Church recites the creed received from the Council of Constantinople—the creed we today call “Nicene”—we confess more about the Holy Spirit than in the Apostles’ creed or in the creed that was actually produced at Nicaea. We speak of the Spirit’s eternal life and earthly mission. And yet we never transgress the divine modesty that is proper to the third person of the Trinity. The council Fathers, it seems, had a precise sense of exactly how far to go—far enough to correct errors, far enough to instill devotion, yet not so far as to eclipse the primary revelation of God’s fatherhood.

According to St. Augustine, the Holy Spirit is the bond of love uniting the Father and the Son. The Spirit is the love shared by the Father and Son. Similarly, the Spirit is the bond of love—the covenant bond—that unites Christians with Jesus Christ. St. Paul spelled this out as he wrote about the New Covenant to the Church in Corinth: “Our competence is from God,” he explained, “who has made us competent to be ministers of a new covenant, not in a written code but in the Spirit; for the written code kills, but the Spirit gives life” (2 Cor 3:5–6).

The Spirit is the life of the covenant, the life of God’s family on earth. It is as the Lord said—as was “spoken through the prophets”:

And as for me, this is my covenant with them, says the Lord: my spirit which is upon you, and my words which I have put in your mouth, shall not depart out of your mouth, or out of the mouth of your children, or out of the mouth of your children’s children, says the Lord, from this time forth and for evermore. — Isaiah 59:21

You Might Also Like

Join Scott Hahn, John Bergsma, and Curtis Mitch for Inflamed and Empowered: Pentecost in Scripture, a virtual event on Saturday, May 30.