The following is an excerpt from the Study Guide of Parousia: The Bible and the Mass, a ten-lesson video study led by Scott Hahn.

As a zealous Evangelical high schooler, Scott Hahn would challenge his Catholic classmates with this question: “Where in the New Testament do you find the sacrifice of the Mass?” Not having a clear understanding of Scripture, his classmates could not refute Scott’s question and some became convinced that their Catholic faith had no biblical foundations.

It would be years later that Scott would come to understand the true meaning of Christ’s words and actions in the Upper Room and on Calvary. He discovered that the Mass was everywhere in the Bible and that the Bible was all about the Mass.

Biblical commentary by early Church Fathers guided Scott to better understand the unity of Scripture. “The New Testament is concealed in the Old and the Old Testament is revealed in the New” was the adage of St. Augustine.

In both the Old and New Testament, the Scriptures presume, prescribe, and describe the ritual life of God’s people. The Bible gives both the content and the context of the liturgy, even as the liturgy provides our context for understanding the Scriptures.

What is liturgy? Liturgy is public service or public work. It is the ritual public worship observed by the people of God both in the Old and in the New Testament.

In the Book of Genesis the cosmos is portrayed as a sanctuary for God’s presence, echoed later by the characteristics of Israel’s tabernacle and Temple. The culmination of creation is when God creates man, namely Adam and Eve. As lord over creation, Adam is given the duties of priest of the sanctuary of Eden, to “till [the garden] and keep it” (Gen 2:15). These two actions, abad and shamar in Hebrew, are his main vocation. But after the Fall, worship and sacrifice change. Adam’s son Cain, filled with envy, kills his own brother Abel in the context of a ritual sacrifice.

Indeed, in Genesis we see the patriarchs performing sacrifices, from Noah in an act of thanksgiving after the flood to Abraham sealing his covenant oaths. As head of their households, fathers perform priestly duties, offering sacrifice for themselves and on behalf of their families, and passing that duty on to their first-born sons. The patriarchs are priests and liturgy is central to the religion they observe.

Liturgy is also at the heart of Israel’s Exodus from Egypt. As part of their liberation from bondage, God’s people observe the Passover ritual, which was instituted as a memorial meal to be observed by future generations. The law of Moses is itself liturgical, instructing Israel in the manner of worship, detailing even vestments and furnishings.

Even entering the Promised Land requires liturgical action from the tribes of Israel. The battle of Jericho is led not by military force but by priestly action, processing around the city blowing trumpets. Once they are settled and at rest from their enemies, God asks David’s son, Solomon, to build Him a house, a temple in Jerusalem where sacrifice may be offered to Him daily.

When prophets begin to rage against the Temple priests, it is not because liturgy or the priesthood is the problem. The problem, as always, is the human heart. It is liturgy done badly and dishonestly, and this is the core of Israel’s downfall.

The centrality of liturgy does not vanish with the coming of the Messiah. Jesus observes the rituals of Israel. He goes to synagogue, makes pilgrimages, visits the Temple, and pays the Temple tax. He does not abolish liturgy but instead establishes new and more powerful rites in the sacraments, especially the Eucharist celebrated in the Upper Room in the context of a Passover. It is a memorial meal where He is the Lamb of God, the Bread of Life, offering His flesh and blood in atonement for sins.

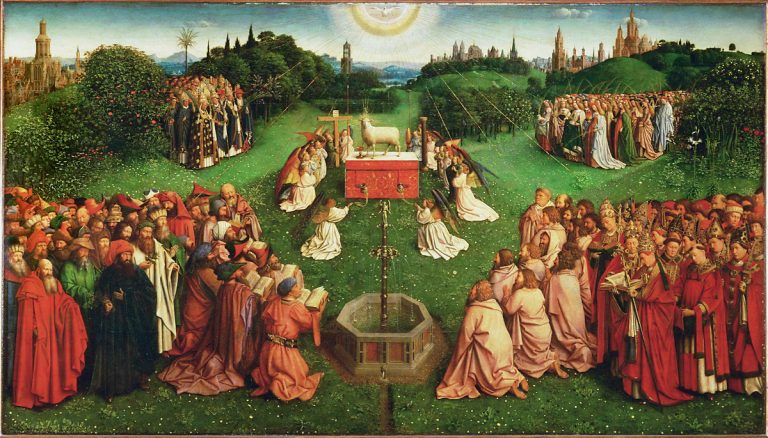

So too, the early Church, learning from her Lord, leads a rich liturgical life. The Acts of the Apostles and other New Testament books include accounts of the Apostles observing rituals: they baptize, break bread, anoint, and lay hands on people. They absolve sins and observe ritual meals. In the Letters to the Romans, Corinthians, and Galatians, St. Paul addresses proper etiquette for meals shared in the presence of God. The Letter to the Hebrews and the Book of Revelation are more focused on the liturgy, portraying the Christian Church as priestly, worshipping around an altar vested for service. All the Scriptures, the Old and New Testament, were written down for the sake of ritual worship.

You Might Also Like

Where do we find the Mass in the Bible? What is the relationship between the two? In ten beautifully produced lessons, Parousia: The Bible and the Mass answers these questions and more.