By Andrew Jones

Andrew Willard Jones is the Director of Catholic Studies at Franciscan University of Steubenville. He is the author of Before Church and State: A Study of Social Order in the Sacramental Kingdom of St. Louis IX and a founding editor of the journal New Polity.

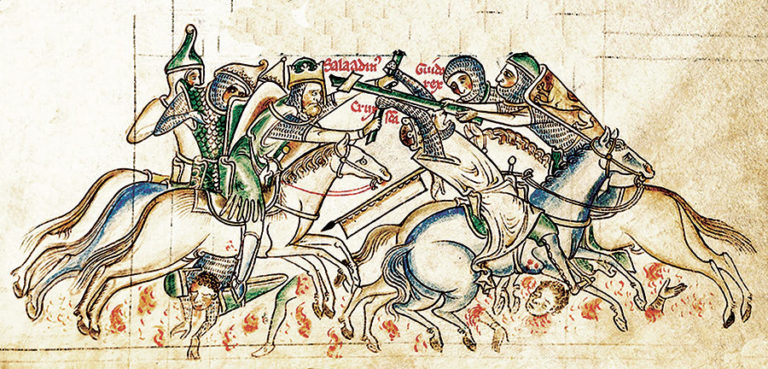

The Crusader, with the Templar as his exemplar, was the perfect example of the chivalric knight, of the good knight. The formation of chivalry was tied directly to this spirituality of Crusade. At the same time, back in Europe, these knights were building kingdoms based on the monastic reform ideals.

The knights who went on Crusade were the knights who at home sought justice, who sought to stop the brigandage and petty warfare of the warrior class, who sought to protect the widows and orphans. They were the kings who built the court systems of Europe, who favored the poor over the powerful. They were the men who sought in the temporal sphere to form the kingdom of God on Earth, as the monks did in the monastery. They sought to sacrifice their entire lives to build a society of charity and faith: going on Crusade against the forces of Islam, forces that, as we have seen, would destroy the kingdom of God, was the ultimate manifestation of this drive.

St. Louis IX of France (r. 1226–1270) is a clear example of the type. He pursued justice in all that he did, devoting his life to the protection of the poor and vulnerable, and he went on Crusade three times, dying on his final expedition. During this period, the power of the sword, the power of what we call the State, was integrated into the pursuit of holiness.

Ultimately, the idea is that the sword can be wielded without sin only if it is wielded always with the intention of peace, always with charity in one’s heart. With such a heart, the use of force becomes Christ driving the money changers from the Temple, or that of a loving father disciplining his child, rather than violence for glory or gain. In such a way, the sword could be integrated into the City of God while it was still on pilgrimage in this imperfect world. But it had to be always integrated into a mission of building a better world for humanity as a whole, integrated into the salvation wrought by the Church.

This is the Christianization of the sword. This Christianization, however, is the scandal of the Crusades in the modern mind.

But is it a scandal? What did the Christianization of the sword entail?

It meant that the sword could not be wielded for gain, for the lust for power or wealth, or even for glory. It meant that the pursuit of territory or resources on their own was never sufficient to initiate armed conflict. It meant that force was properly deployed in society and against foreign enemies only in response to injustice and always with the purpose of reinstituting peace and of building a just society. It meant that one, ultimately, ought to love one’s enemies, even if you are compelled to fight them to the death. It meant that the warrior had to sacrifice himself in charity. This was dramatically different from the ethos of war found in paganism and found throughout most of human history and in almost all human societies.

The Crusades gave us the notion that war ought not to be fanatical, suicidal, homicidal, or based on power and greed. They gave us the notion that a war ought only to be fought when it fits into a universal notion of right and wrong and so is directed always toward the good of all people. Wars ought to be fought not simply when one thinks one can win, or even when one thinks that a war might be justified, but rather, wars ought to be fought only when duty to what is right demands that the sword be taken up, and the people who fight in such wars should properly be doing so as an act of self-sacrifice, as a gift to others. This is the ethical legacy of the Crusades. Another way of saying this is that Crusaders gave us the notion that all wars ought to be, in a sense, holy—otherwise, they shouldn’t be fought.

This is why, when Crusaders failed to live up to the ideal, when they gave into fanatical passion and did things like persecute Jewish communities or gave into greed and attacked Christian cities for gold, which they sometimes did, they were condemned by their fellow knights and excommunicated by the popes and bishops; for when they behaved this way, they were like the barbarians again, or like the pre-chivalric feudal knights. They were no different from the forces of evil that they were supposed to fight, having crossed over to the City of Man. This is the notion of war crimes, of morality in war. And this we owe to the Crusaders.

You Might Also Like

In The Two Cities: A History of Christian Politics, Andrew Willard Jones rewrites the political history of the West with a new plot, a plot in which Christianity is true, in which human history is Church history. It advances a theory of Christian politics that is both an explanation of secular politics and a proposal for Christians seeking to navigate today’s most urgent political questions.