By Scott Hahn

Jesus promised repeatedly that the kingdom was coming without delay. Midway through the “little apocalypse” of Matthew’s Gospel, Jesus says: “Truly, I say to you, this generation will not pass away till all these things take place” (Matt 24:35).

The early Christians expected immediate fulfillment of Jesus’ prophecies. They expected an imminent parousia. Modern historians have found evidence of this expectation throughout the New Testament and the earliest Christian writings. The most ancient Eucharistic prayer that has survived, in the Didache, ends with the Aramaic word Maranatha, that is, “Come, Lord!” The Book of Revelation begins with a promise to show “what must soon take place” (Rev 1:1) and ends with the same words as the liturgy in the Didache: “Come, Lord Jesus!” Biblical scholar Margaret Barker has identified this word— Maranatha!—as the Church’s primal Eucharistic prayer: “This links the return of the LORD to the Eucharist. Other lines of the [Didache’s] prayer are ambiguous: ‘Let this present world pass away’, for example, could imply either a literal understanding of the LORD’s return or the present transforming effect of the Eucharist. Maranatha in the Eucharist, however, must be the original epiklesis, praying for the coming of the LORD.”

Modern historians are right to point out the expectation of the apostolic age. They go wrong, however, when they conclude that the early Christians must have been disappointed with the passing of time. The apostate scholar Alfred Loisy observed that Jesus came promising the kingdom, but all He left behind was the Church. Loisy was disappointed by this turn of events, but the early Christians most certainly were not.

The early Christians knew that there would indeed be a parousia at the end of time, but there was no less a parousia right now, whenever they celebrated the Mass. When Christ comes at the end of time, He will have no less glory than He has whenever He comes to His Church in the Mass. The only difference, then, is in what we see.

Faced with the evidence of the ancient liturgies, skeptics will sometimes resort to psychoanalyzing the ancients. They say that the idea of a “liturgical parousia” was a late development and a coping mechanism for a disappointed Church. But it wasn’t late. Gregory Dix notes that it is in the very earliest documents; indeed, some scholars estimate that the liturgy of the Didache could have been written no later than 48 A.D. After reviewing all the ancient Eucharistic texts, Jaroslav Pelikan concludes: “The Eucharistic liturgy was not a compensation for the postponement of the parousia, but a way of celebrating the presence of one who had promised to return.”

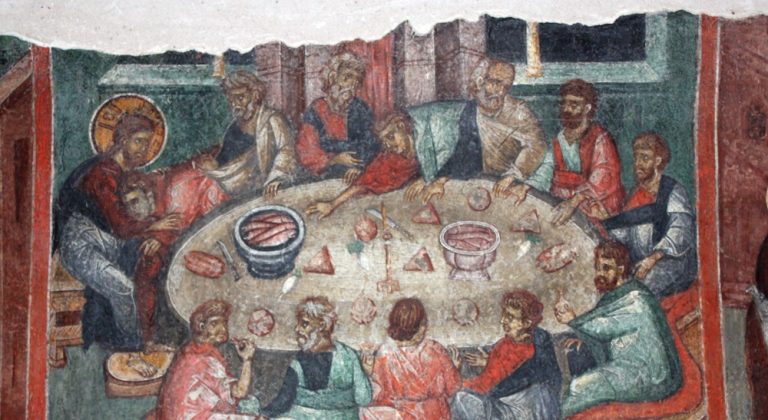

After all, it was Jesus Himself Who set such a high level of expectation in the Church; and it was Jesus Himself Who pointed to its imminent fulfillment. Indeed, it was Jesus Who established the Eucharist as an eschatological event—a parousia—a coming of the King and the kingdom. We must not miss the small but significant details in the scriptural accounts of the Last Supper. As Jesus takes the bread and wine, He says to His apostles: “I have earnestly desired to eat this Passover with you before I suffer; for I tell you I shall not eat it until it is fulfilled in the kingdom of God. . . . I shall not drink of the fruit of the vine until the kingdom of God comes” (Lk 22:15–16, 18). As He institutes the sacrament, He institutes the kingdom. A moment later, He is speaking of the kingdom in terms of a “table” (22:27) and a “banquet” (22:30)—language that will recur in the final chapters of the Book of Revelation. If we are looking for familiar apocalyptic language, we will find it aplenty in Luke’s account of the Last Supper—but we will find it always expressed in Eucharistic terms. Jesus goes on to speak of apocalyptic trials, in which believers are “sift[ed] like wheat” (22:31).

No less an authority than Joseph Ratzinger has noted that the New Testament’s apocalyptic imagery is overwhelmingly liturgical, and the Church’s liturgical language is overwhelmingly apocalyptic. “The parousia is the highest intensification and fulfillment of the liturgy,” he writes. “And the liturgy is parousia. . . . Every Eucharist is parousia, the Lord’s coming, and yet the Eucharist is even more truly the tensed yearning that He would reveal His hidden Glory.

Dr. Scott Hahn is a world-renowned biblical scholar and author of over forty books. This article is adapted from his book Scripture Matters: Essays on Reading the Bible from the Heart of the Church, which offers just what the title implies: an accessible and comprehensive introduction to reading the Bible from the Heart of the Church.