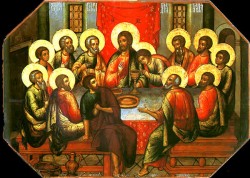

Whether you hold, with some Syriac Fathers, that Christ instituted the Eucharist on Tuesday — or, with the Western tradition, that He instituted it on Thursday — today, Holy Thursday, is the day the Catholic Church remembers the event liturgically. I’m about to leave with my kids for the Chrism Mass in my diocese. It’s a great sight for children to see every year: all the priests of the local Church gathered around their local bishop at the Lord’s table — just as Ignatius described the Eucharist in Antioch around 105 A.D.

To mark the day, I give you this, adapted from my book The Mass of the Early Christians.

The Mass of the early Christians was a familiar and intimate thing. It was, for the Fathers as for the Apostles, the defining action of Christian life. Through the times of persecution, daily communion was fairly commonplace.

Christians were “at home” with the Mass. And yet their reverence was profound. In the third century, Origen noted that when his hearers “receive the Body of the Lord, you guard it with all care and reverence lest any small part should fall from it, lest any piece of the consecrated gift be lost.” In the fourth century, Cyril of Jerusalem exhorted his people. “Tell me, if anyone gave you grains of gold, would you not hold them with utmost care, on guard against losing any? Will you not take greater care not to lose a crumb of what is more precious than gold or jewels?”

That reverence extended to the liturgical vessels as well, which were always made of the finest materials the local Church could afford. Origen’s African contemporary Tertullian described chalices richly decorated with images of Christ. And in the midst of the last persecution, in 303, a Roman court in North Africa recorded that the following items had been confiscated from a church: two golden chalices, six silver chalices, six silver dishes, a silver bowl, seven silver lamps, two torches, seven short bronze lampstands with their lamps, and eleven bronze lamps on chains.

In the following century, St. Jerome would write of the need “to instruct by the authority of Scripture ignorant people in all the churches concerning the reverence with which they must handle holy things and minister at Christ’s altar; and to impress upon them that the sacred chalices, veils and other accessories used in the celebration of the Lord’s passion are not mere lifeless and senseless objects devoid of holiness, but that rather, from their association with the body and blood of the Lord, they are to be venerated with the same awe as the body and the blood themselves.”

This care for liturgical detail followed from the Church’s belief in the Real Presence. “For anyone who eats and drinks without discerning the body,” wrote St. Paul, “eats and drinks judgment upon himself” (1 Cor 11:29). Indeed, St. Ignatius of Antioch (writing in 107 A.D.) said that the distinguishing mark of heretics was their denial of the Real Presence: “They abstain from the Eucharist and from prayer, because they do not confess the Eucharist to be the flesh of our Savior Jesus Christ.” St. Justin Martyr, four decades later, wrote that “the food blessed by the prayer of his word … is the flesh and blood of Jesus who was made flesh.” Q.E.D.

This presence was abiding, not something that vanished at the conclusion of Mass. St. Justin described deacons taking Communion to the sick and homebound. Tertullian described Christians, in time of persecution, reserving the sacrament at home for daily communion. And Hippolytus, in third-century Rome, urged Christians to tabernacle the sacrament where no mouse could nibble at it. “For it is the body of Christ … and not to be treated lightly.”

The Church held to this understanding from the start, and it is especially evident in her language of prayer. The theological vocabulary developed more gradually, often in response to abuses and heresies When some teetotaling African clergy began celebrating Mass without wine, St. Cyprian urged them to return to the traditional practice. For the heretics were taking away many things, he said: a divinely appointed image of the blood of Christ and a beautiful symbol (in the mixed cup of wine and water) of the union of the people with Christ. A generation earlier, Irenaeus (writing around 180 A.D.) had pointed out that the mixed cup was also a symbol of the union of Christ’s divine and human natures. So liturgical abuses, even if they sprang from good intentions, could have serious doctrinal consequences.

For the Eucharist is a test and measure of Christian faith. Irenaeus’s words still ring true today: “Our way of thinking is attuned to the Eucharist, and the Eucharist in turn confirms our way of thinking.”