By Scott Hahn

Dr. Scott Hahn, founder and president of the St. Paul Center, is the author of over forty books, including The First Society, The Creed, and Understanding "Our Father".

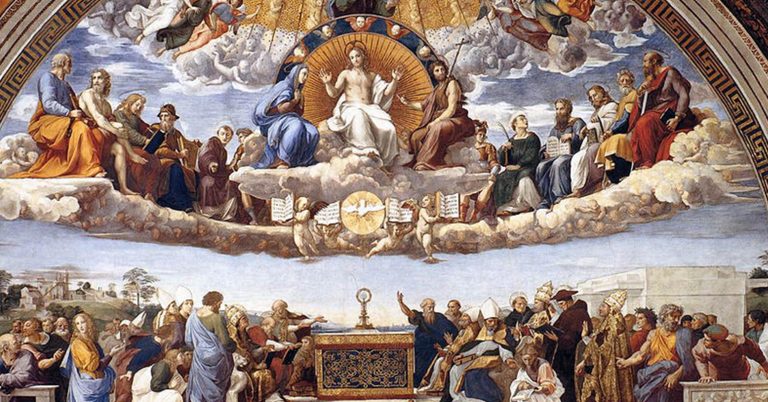

The sacraments are what God had in mind for you and me “in the beginning,” when He made the heavens and the earth. The sacraments are what He brought about, little by little, all through the Old and New Testaments.

This may come as a surprise to many readers. Though we Catholics love and revere the sacraments, too often we treat them as something the Church teased out of a smattering of New Testament proof-texts. That notion, however, is precisely backwards. It would be more accurate to say that the Bible is what God’s people teased out of a providential plan in which God’s New Covenant sacraments were already present “in mystery” (to steal a phrase from the Church Fathers) from the first moments of the Old Covenant.

There is a unity to the two Testaments of the Bible; and the whole of the Bible is inseparably united with the small details of the Church’s life today.

Jesus Himself read the Old Testament this way. He referred to Jonah (Matt 12:39), Solomon (Matt 12:42), the Temple (John 2:19), and the brazen serpent (John 3:14) as signs pointing to His own life, death, and Resurrection. Toward the end of Luke’s Gospel, Jesus took “Moses and all the prophets” and “interpreted to [His disciples] in all the scriptures the things concerning himself” (Luke 24:27). Saint Paul followed His Master in this reading of the Hebrew Scriptures (cf. Rom. 5:14, Gal 4:24), as did Saint Peter (cf. 1 Pet 3:20-21). Saint Augustine summed up this interpretive method in a single phrase: The New Testament is concealed in the Old, and the Old is revealed in the New.

What unites the two Testaments is what unites God and mankind. In the Bible, this bond is called the “covenant.” A covenant, in ancient cultures, was a solemn agreement that created a family relation. Marriage was a covenant, as was the adoption of a child. When a family welcomed a new member, both parties would seal the covenant by swearing a sacred oath, sharing a common meal, and offering a sacrifice. Periodically, the two parties might repeat the sacred oath, along with the meal and sacrifice, in order to renew the covenant bond. This is how God made His covenant with Moses, for example, a covenant that was renewed annually in the Passover seder meal.

Nor did this arrangement end with our redemption by Jesus Christ. Indeed, the one and only time Jesus mentioned the New Covenant was in the context of His last Passover meal, as He culminated the sacrifice of His life. The only time He mentioned the New Covenant was when He offered His body and blood at the first Eucharist (Luke 22:20). Moreover, Jesus commanded His apostles to renew the covenant with God by the same means. “Do this,” He said, “in remembrance of me” (1 Cor 11:25).

From the earliest times, Christians commonly called this action by the Latin word sacramentum. We find that word not only in the works of churchmen such as Tertullian (207 A.D.), but also in the documents of pagan officials who were investigating and persecuting the Church. Around 112, a Roman governor named Pliny the Younger used the word to describe the ritual worship of the Christians. And what does sacramentum mean in Latin? It means “oath.” Pliny said that the Christians in His province of Bithynia met before dawn to sing hymns and bind themselves by oath to Christ, as they shared “an ordinary kind of food.”

Thus, in the witness of the early Church—and in the practice of our parishes today—we see the Old Covenant oaths revealed and fulfilled in the New Covenant sacramentum. All history, guided by the Holy Spirit, has led you and me to these specific moments of sacramental grace.

That’s why most Catholics love the sacraments. We experience them as beautiful and dramatic ceremonies marking life’s most emotional moments: a wedding, the birth of a child, the throes of a serious illness. Even the sacraments we receive more often we can associate with peak experiences. We remember the catharsis of a good Confession. Or our eyes well up at the sense of antiquity we get from a Sunday Mass in our old home parish.

All those emotions and associations are good. If we love the sacraments for their ceremonial beauty—if we revere them for their ancient tradition—if we experience them intensely—we’ve begun to see what they are. But we’ve only begun, and we have much more yet to see. Indeed, there’s much more God wants us to see, intends us to see, and all but commands us to see.

To see the sacraments as God wants us to see them, we need to see more than the externals, more than the rituals. It’s not that we should ignore the externals; we must never do that, because it’s by their “outward signs” that we know the rites as sacraments. Still, the outward signs do not come close to revealing the fullness of the inner realities. So we need to see the sacraments “inside,” too, if we’re to see them as they are.

The liturgy, which includes the seven sacraments, is the context for which all the Scriptures were written. In those many centuries before the printing press was invented, God’s people received His Word primarily during the liturgy—in the readings at Mass, and in the liturgical prayers themselves, which were saturated with scriptural quotations and allusions. The primary means of biblical teaching and interpretation in the early Church was the homily of the local bishop.

For a Catholic, there’s a very real sense in which little has changed since the days of the Acts of the Apostles. The Church continues to meet daily for the breaking of the bread and the prayers. Every day, the Church requires readings from both the Old and the New Testaments. And today, just as almost 2,000 years ago, those readings are not arranged arbitrarily; they’re arranged typologically, so that we can hear the New anticipated in the Old, and the Old fulfilled in the New. This is the way we come to see how covenants work, and how we come to know the New Covenant in the breaking of the bread. Once we can see these matters clearly, we will see the sacraments—inside and out—as they have existed in God’s fatherly plan for us from all eternity.

You Might Also Like

Sacraments in Scripture: Salvation History Made Present is a Bible study on the seven sacraments, prefigured in the Old Testament and instituted by Jesus Christ in the New. Following the teaching of the Second Vatican Council and the Catechism of the Catholic Church on Sacred Scripture, Tim Gray delves into the biblical origin of each of these masterpieces of God’s love. In Sacraments in Scripture, Tim Gray guides readers through the Gospels, showing Christ’s deliberate acts that inaugurated these sacred signs as the foundation of the New Covenant.