By Brady Webb

Brady Webb is a Director of Religious Education in the Diocese of Wheeling-Charleston. He currently resides with his wife, Christine, and spider plant, Master Wayne, in Steubenville, OH.

As a westerner, I struggle with something that I think most of us do. We are highly materialistic. I don’t mean that we don’t necessarily believe in God. I mean that even as Christians, we have an unhealthy attachment to wanting things to make sense to us according to the senses and the scientific method. A prime example of this materialism is the major flaw of reading Scripture from a fundamentalist perspective: Genesis is seen as a literal account of what, where, why, how, and in what way God made the universe. As Catholics, we read the Bible literarily, considering the various genres of each book of the Bible.

We know that as the inspired word of God, Genesis is infallibly true. But how is it true? Genesis 1-12 is a mythic-poetic account of creation: the truth comes as myth and poetry. Neither the divine writer nor the human writer is concerned with giving a scientific account of creation and its material causation. If we get stuck in a materialistic mode of reading Scripture, we entirely miss the point. As Catholics, we can honestly and truly say that material causation is not what Genesis 1-12 is about. This passage about the world’s beginning is told without any scientific reference or exact chronology. How can this be? It is because we have, if I may say so, entered something close to a fairy tale.

Just as with Genesis 1-12, so with Santa Claus. There is no hard line between facts discoverable via the scientific method and truths communicated through myths (or fairy tales). The great G.K. Chesterton was a citizen of both fairy land and England. He knew that though strange and fantastic on the outside, fairy tales bear deep truths about reality within them.

Here is an interesting reflection about Chesterton’s experience with make-belief as a child:

I am inclined to contradict much of the modern Cult of the Child at Play. Through various influences of a recent and rather romantic culture, the Child has become rather the Spoilt Child. The true beauty has been spoilt by the rather unscrupulous emotion of mature persons, who have themselves lost much of their sense of reality. The worst heresy of this school is that a child is concerned only with make-believe and belief. But the real child does not confuse fact and fiction. He simply likes fiction. He acts it, because he cannot as yet write it or even read it; but he never allows his moral sanity to be clouded by it. 1

Modern studies have affirmed that children have a strong grip on reality even in the midst of fairy land. There is no lie in supporting childlike make-believe.

But even if it is not a lie, does it not still harm children to discover that Santa is not exactly what they thought? Chesterton remembered the toy theater from his childhood and his experience of awakening to the “material” reality that the puppets were not really alive, and that his father was behind it all:

There was nothing of illusion or of disillusion. If this were a ruthless realistic modern story, I should of course give a most heartrending account of how my spirit was broken with disappointment, on discovering that the prince was only a painted figure . . . I do not remember that I was in any way deceived or in any way undeceived. The whole point is that I did like the toy theater even when I knew it was a toy theater. 2

In other words, there was no harm done to Chesterton just because the fantasy world and the physical world were intertwined. On the contrary, the experience of fairy land is enriched by learning the physical facts. His experience of Santa Claus was like that of the toy theater:

I was not merely tricked or trapped . . . For the same reason I do not think that I myself was ever very much worried about Santa Claus, or that alleged dreadful whisper of the little boy that Father Christmas ‘is only your father.’ Perhaps the word ‘only’ would strike all children as the mot juste. 3(the shock)

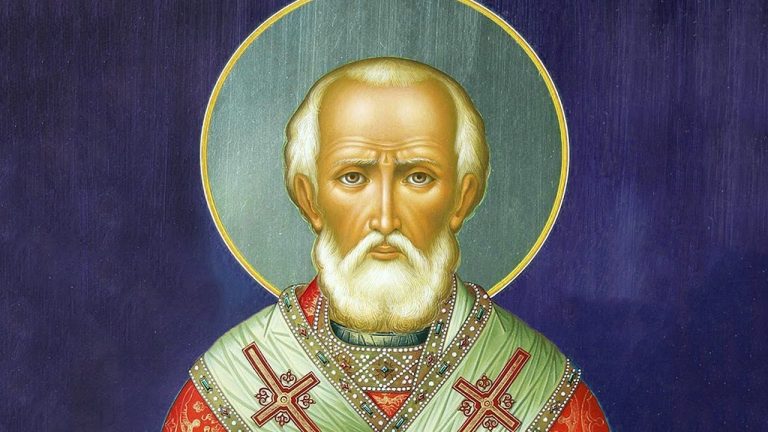

For Chesterton, there was no problem in saying that Santa was his father, as long as he was not only his father. Santa could be traced back to Nicholas of Myra as long as he was not simply Nicholas of Myra. The moment that we qualify a fairy tale or myth based primarily on empirical standards, we lose the myth and the truth that accompanied it. How, then, did Chesterton approach belief in Santa?

I startled some honest Protestants lately by telling them that, though I am (unfortunately) no longer a child, I do most definitely believe in Santa Claus; though I prefer to talk about him in my own language. I believe that Saint Nicholas is in heaven, accessible to our prayers for anybody; if he was supposed to be specially accessible to prayers of children, as being their patron, I see no reason why he should not be concerned with human gifts to children. I do not suppose that he comes down the chimney; but I suppose he could if he liked. The point is that, for me, there is not that complete chasm or cutting off of all relations with the religion of childhood, which is now common in those who began by starting a new religion and have ended by having no religion. 4

Imagination via fairy tale is meant to deepen into a reservoir of truth not able to be grasped by the sciences alone. If we cut off that fairy tale as “not true” or “impossible” we are only bowing to the god of materialism and killing the imagination. Chesterton said that “If things deceive us, it is by being more real than they seem. As ends in themselves they always deceive us; but as things tending to a greater end, they are even more real than we think them.” 5 The fairy tale is not an end in itself, but points beyond itself and ultimately to the truth which rests in God.

Santa, as a myth, points to gratitude for everything, even the gift of life itself. Even better, he represents the gift of new life in Christ. He may even (according to the rules of fairy land) represent the Christ child himself. I leave you with Chesterton:

The test of all happiness is gratitude; and I felt grateful, though I hardly knew to whom. Children are grateful when Santa Claus puts in their stockings gifts of toys or sweets. Could I not be grateful to Santa Claus when he put in my stockings the gift of two miraculous legs? We thank people for birthday presents of cigars and slippers. Can I thank no one for the birthday present of birth? 6

- G.K. Chesterton, The Autobiography of G.K. Chesterton, (New York, NY: Sheed and Ward, 1936), 39.

- Ibid, 44.

- Ibid, 44-45.

- G.K. Chesterton, “Santa Claus and Science,” The Commonweal (New York, NY), December 20, 1935. (http://www.commonwealmagazine.org/sites/default/files/imce/31076/santaclausandscience.pdf), 201.

- G.K. Chesterton, Saint Thomas Aquinas, (New York, NY: DOUBLEDAY/Random House, 1956), 151.

- G.K. Chesterton, Heretics & Orthodoxy, (Breinigsville, PA: Merchant Books, 2014), 178.

You Might Also Like

G.K. Chesterton, as author David Fagerberg convincingly proposes, is as relevant today as he was at the turn of the last century. Chesterton is Everywhere is a charming collection of essays that apply the thought of the great English writer to everyday and eternal subjects.