By Msgr. Robert Nusca

In the Book of Revelation, John’s spectacular visions of renewal can provide joyful reassurance in times of crisis and upheaval. But neither does he lack any of the somber realism of Isaiah’s watchman who reminds us that “morning comes, and also the night” (Is 21:12). The New Jerusalem has appeared on the horizon, but the “sea of glass mixed with fire,” with its dangers and trials, remains before us. From the watchtower of the prophet’s Spirit-inspired perspective, both Isaiah and John remind us that empires fall, and with them their altars and the images of their gods.

As one world comes to an end and the New City looms ever larger upon the horizon of the Spirit, John calls us to seek the Face of God through the Faces of Christ and so begin to recover the image of humanity’s highest self—the goal and end for which humanity was created—as we strive to see with the eyes of Christ. It is in this way, we can discover that new beginning which is already taking shape in the midst of this world’s chaos, suffering, impurity, and death, and so become even now, a new creation in Christ (2 Cor 5:17).

In response to those who would argue that religion is dead, Revelation’s Jewish-Christian apocalyptic hope beckons us to look for the light amid the passing shadows of time and to make room for the God who is the source of all light. Beyond the intellectual clouds, philosophical stars, and ideological constellations, behind which God has been eclipsed in our time—from Adam’s spirit of rebellion to the “apatheism” that marks the present age—let us, as Rabbi Abraham Isaac Kook invites us, look for a new beginning precisely in the shadows that are stirring to make way for the light:

People believe that religion is dying, that the world is being overturned. In truth, however the shadows are stirring, they are in flight in order to make room for the light. If religious faith is to be revitalized, a great effort is needed to deepen the knowledge of God, to follow the most subtle paths of mystical thinking through which one rises above every kind of limitation to God.119

So it is that Rabbi Kook calls us to strive to look beyond “the letters, the words, the vessels of the light, to the Light itself.”120 While it may not be given to us to change the world, we have no excuse for not changing ourselves by entering ever more deeply into the mysteries of God and the soul, as Augustine reminds us (Soliloquies I.4). As one modern theologian comments, “the Christian of the future will be a mystic or he will not be a Christian at all.”121

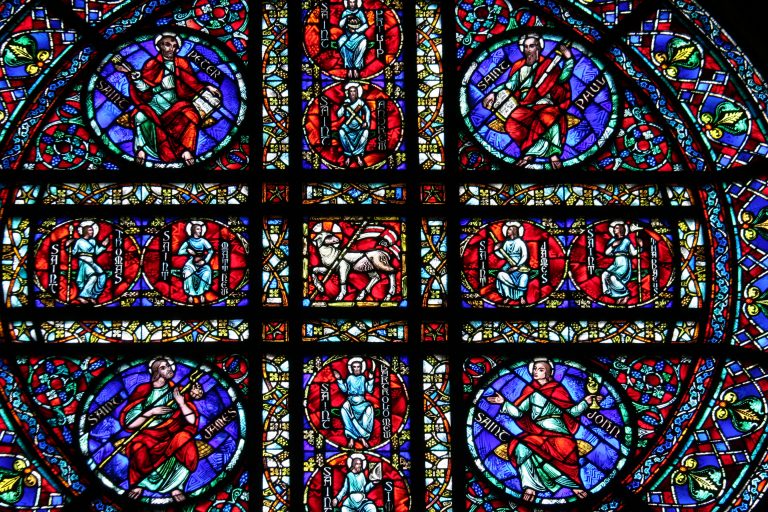

Dogmatic formulations, Codes of Canon law, and beautiful art and architecture all have their place. But in the New Jerusalem, John sees neither sun nor moon, nor temple, as a priestly and prophetic people encounters the glory of God’s presence without mediation (22:4–5; cf. 1:7), for God and the Lamb are themselves the City’s temple and its everlasting Light (21:22–23).

Amid the sorrows and disorders of this passing life of shadows, St. John calls us to strive to become that well-ordered city whose temple is God Almighty and the Lamb (21:22). Here, amid the visions of the end of the world John opens for the Churches the door to the most profound mysticism in the eternal now of the worship life of a community of faith “poised on the boundary between earth and heaven.”122

Cardinal Jean Daniélou offers insights on how we are to live in two worlds at the same time. He writes:

We must not be without a country on our arrival in heaven. Our Life is an apprenticeship. It is a matter of learning the rudiments of what we shall have one day to do. So let us already try in prayer to stammer what will later be the “conversation in heaven” with God and his angels; so we must try to make less crude this intellect of ours, which is so immersed in the world of time and space, and to acclimatize it gradually to heavenly things through the action of the gifts of the Holy Spirit. Thus charity itself is the clumsy beginning of that complete communion which will embrace all the saints. 123

Like Ezekiel’s visions of God’s celestial throne (cf. Ezek 1 and 10), John’s christianized apocalyptic recreation of the heavenly world sets before the religious imagination of the Churches of Asia Minor the sparkling throne of God and the Lamb that stands forever beyond the power of the Roman Emperor and “inaccessible” to any military force.124

Where the Temple no longer stands, where the community of faith walks in exile by the waters of the river Chebar (cf. Ezek 1:1), God’s glory moves with His people, shining forth through the voice and Spirit-inspired vision of the prophet. John’s visions do not merely point to future salvation; they convey in the present time the divine call “to participate actively in the vital process of the world’s re-creation,” and so strive to rebuild the ancient ruins and renew the ruined cities (cf. Is 61:4; 44:26). The audience is called to that newness of life which God and the Lamb are bringing about in the midst of opposition to the arrival of the Kingdom. As faithful witnesses, they participate—even now—in the cosmic transformation elaborated so compellingly in John’s visions of a new heaven and a new earth in Revelation 21–22.

With St. Ephrem of Syria, let us pray that as we journey toward the everlasting city we may “see it now in a vision, like Moses on the mountaintop.”125

Msgr. Robert Nusca’s The Christ of the Apocalypse: Contemplating the Faces of Jesus in the Book of Revelation offers insight into one of the most misunderstood books of Scripture by uncovering the presence of Our Lord within its pages.