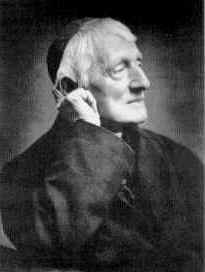

My co-author Fr. Juan Velez is talking up Blessed John Henry Newman at First Things’ blog! (Our book is TAKE FIVE WITH JOHN HENRY NEWMAN.)

John Henry Newman, Oxford scholar and famous English convert to Catholicism (1801–1890), whose birthday we celebrate today, is acknowledged by most for his English prose, his lofty ideas on university education and his writings on development of Christian doctrine. We often put Newman forward as an example for the Catholic intellectual but rarely consider what he has to say to the average person striving to live a Christian life in a secular world. But Newman was also a pastor and his parochial sermons were addressed to his parishioners and students—average people striving to live a Christian life in an increasingly secular world.

One of the major themes in his sermons was faith and obedience to God. Newman urged his listeners on to child like simplicity and trust in God, which enable children to listen to and receive with awe descriptions or tales. Newman comments on how a child’s mind gives us a striking pattern “of what may be called a church temper”: Children distinguish right from wrong yet are free from a proud spirit of independence. They are ready to learn from others; they don’t set themselves as the measure of truths. This makes them most receptive of faith because “Christ has so willed it, that we should get at the Truth, not by ingenious speculations, reasonings, or investigations of our own, but by teaching.”

Newman countered the Enlightenment’s understanding of reason, a reduced notion of reason, which sets itself as the judge of all truth and demands scientific evidence, arguing that faith in God is possible without formal evidence. In fact, as Newman points out, many truths are received implicitly. Often people cannot explain what they know to be true and yet this does not diminish the truth of their claims.

An Englishmen may never have traveled to the shore, but he is absolutely certain that England is an island. What’s more, knowledge held implicitly is often held most strongly. Newman did not give weight to “paper arguments” about God’s existence; as he wrote: “Many a man will live and die upon a dogma: no man will be a martyr for a conclusion. . . . No one, I say, will die for his calculations: he dies for realities.”

As a young clergyman, and even earlier, Newman gave a lot of thought to the question of faith, the assent of the mind to what God reveals through the Bible and the Church. His dealings with his brother Charles and others made him think a lot about faith in relation to revelation, Tradition, and the Church. It was, however, in correspondence with William Froude, a younger brother of his friend Richard Hurrell Froude, that Newman developed his understanding of faith. Their correspondence over many years became the foundation for one of Newman’s major works, An Essay in Aid of a Grammar of Assent.

In Grammar of Assent Newman explained that for a child, God is a real being. A child perceives the existence of God as a Sovereign Law Giver and Judge, someone outside of himself. God is not a notion or a conclusion.

By means of his moral conscience a child has an image of God; it is basic and must grow, and can be dimmed or obliterated, but it is real. “It is an image of the good God, good in Himself, good relatively to the child, with whatever incompleteness; an image, before it has been reflected on, and before it is recognized as a notion. Thought he cannot explain or define the word “God,” when told to use it, his acts show that to him it is far more than a word.” Something similar can be said for many adults: They cannot explain religious truths, but they know them because they have a moral conscience that speaks to them of right and wrong, and of a Law Giver and Judge.

In the same way, all men can have this real knowledge of God—faith—in that he creates, provides, judges, rewards and punishes. The certainty of this faith, however, is soon questioned. Over the years Newman and William Froude discussed the subject of certainty and certitude. Froude claimed the right to skepticism of any truth: “Our doubts in fact, appear to me as sacred, and I think deserve to be cherished as sacredly as our beliefs.” In a reply to Froude, Newman distinguished between religion and science: “Much lies in the meaning of the words certainty and doubt—much again in our duties to a person, as e.g. a friend—Religion is not merely a science, but a devotion.”

Unlike in science, Newman argued, evidence is not the foundation for faith. Newman defended the rationality of “simple faith.” Still Newman tried to find an adequate answer to the problem of the certitude of the assent of faith, and he dedicated part two of the Grammar of Assent to explain how a person reaches certitude. He called this the illative faculty or sense. This is a natural mode of reasoning which in unconscious and implicit; it goes from concrete thing to other things, not from propositions to propositions as formal inference or logic.

A man reaches certitude through this illative sense. A skeptic might reply that this is tantamount to a leap of faith, but there is no such leap because the assent of faith has a cumulative and pain staking dimension; we grow into a conviction, rather than leap into it. Newman used the example of a polygon inscribed in a circle. As its sides become smaller it tends to become the circle. It never becomes the circle but the mind closes the gap.

Faith is a personal act (not a subjective one) by which a person apprehends religious truths from others. As noted, for Newman, humility—a child-like spirit—is a necessary condition for belief. Without humility one is incapable of believing in God; a person establishes his own universe and close him or herself to any supernatural reality. Pride closes a person in a limited sphere of rationality.

At times belief in the indissolubility of marriage, the Pope’s authority, the Real Presence, or other doctrines are difficult to explain; and some Catholics don’t know how to explain them. Obedience of faith still holds claim of the believer’s mind, which subjects itself to God who reveals himself and speaks through the Church. Unlike theological propositions, faith is not a logical conclusion. It is a higher knowledge, which is not contrary to reason, but which admits of an order higher than that of science.

When God reveals himself man must act on God’s terms, accepting with humility what God reveals. Newman did just that in his life, making him an example for not only intellectuals and academics, but all Christians. Returning to England after a long Mediterranean journey and a life-threatening illness, Newman composed “Lead Kindly Light,” humbly asking God to lead him on. Although once “pride ruled my will,” he prays, “Keep Thou my feet; I do not ask to see / The distant scene—one step enough for me.”