A conversation with Fr. Arne Panula by Mary Eberstadt

Mary Eberstadt: How and why did you end up becoming a priest?

Fr. Arne: I don’t have a spiel. My father was not Catholic. He wasn’t anything—Lutheran Finnish. He converted when I was in Rome. My mother’s maiden name was Bellinger— Welsh-Scottish. Ours wasn’t particularly a pious home. We said grace, prayed the Rosary for a year or two, went to Mass. My father would drive us, because mother didn’t drive. I have three sisters—an older, a twin, and a younger; and a brother who died in childbirth. I started serving Mass in middle school. The pastor offered to send me to St. Thomas Seminary in Minnesota. My academic strengths were in math and science; a good friend of my father had gone to MIT, and that became my aspiration. Politics never interested me. My parents were both Democrats; I always disdained politics. Between my junior and senior year of high school I went to Corvalis, Oregon, for a six-week program, National Science Foundation; and the following summer, to a similar program at University of Minnesota.

That was an intellectual awakening, and not because of the science. We’d stay up till 2:00 in the morning, talking about life, etc. I made a number of good friendships. In the fall I applied to MIT, University of Chicago, and Harvard. The Harvard catalog was of interest for offering the greatest breadth [beyond the sciences], so I accepted and started in the fall of 1963. Two friends of mine also went to Harvard.

Where does Opus Dei enter the story?

Fr. Arne: My older sister went to study at Michigan Tech, and when I visited her during her first year there she showed me the Catholic student center—chapel, library, resident chaplain. She and I were intellectually the closest of the siblings, and I knew right away that I wanted something similar wherever I might go to study. Later at Harvard, after Sunday Mass, the school cafeteria was closed; so I’d end up in the Catholic coffee place. I met a Filipino grad student who told me of a place with a chapel and fellowship with others. He was also talking with a number of others from South America, and at first I thought this was too international a crowd for me. But as I was leaving, he stopped me, and eventually we walked over to Elmbrook Residence at the opposite side of campus. It seemed like a good place to study, so I started hanging around.

I had no plan of becoming a priest, not then. But the idea of sanctity in the everyday things of the world—a pillar of St. Josemaría’s spiritual thought—was one I found deeply attractive. The day after Kennedy was assassinated, my Filipino friend suggested that I join Opus Dei.

As of my sophomore year, I had a profound sense that something was wrong. It seemed to me that Harvard was full of intellectual glibness. At the time, I was reading in the philosophy of history, which moved me to study more in the fields of history and English; and English literature became my major, despite my longer-standing foundations in math and science.

In retrospect, something else telling happened that year. I was assistant manager of the Harvard crew team, and there was a young fellow on it with whom I’d talk about English lit. He ended up dropping out, and the next year I saw him in uniform. He was killed in Vietnam.

It bothered me that I hadn’t talked to him more deeply about faith. I wondered whether that might have made a difference to where he ended up after death. That was my first conscious thought of spiritual fatherhood.

I was living in Eliot House and having conversations, and sometimes arguments, with a wonderful rotating set of characters. Still, my studies had ceased commanding my full attention; the feeling that something was wrong at Harvard, and elsewhere in the sophisticated world, preoccupied me. By senior year, I had developed the game plan of going to Harvard Business School. I thought I’d become an investment banker, a pinstripes guy.

But then one of the regional directors of Opus Dei suggested that I go to Rome on a fellowship. I liked the idea. I got into business school as planned, but deferred.

It was 1967—the so-called “summer of love.” I ended up staying in Europe for two years studying philosophy and theology, mostly in Paris, Rome, and in a little town in the Apennines. Ultimately, I ended up staying in Europe for six and a half years—passing through Paris, living in Rome for two years to study philosophy and theology, and then studying in Pamplona, Spain, where I finished my doctoral dissertation. This inoculated me for good against the druggie-hippie culture of those years, but I still wasn’t drawn to the priesthood. Then I met St. Josemaría shortly after arriving in Rome.

What were your first impressions of him?

Fr. Arne: He had a great sense of love of God; a great sense of humor; he was very strong, despite the pain that he suffered because of the way the Church was being torn apart from within following the Second Vatican Council.

I asked him once: “Father, what do you think of the new liturgy?” There was a pregnant pause, and he replied, “I will obey.”

That was a significant moment for me. I was impressed by his strength of character and his obedience at the same time. He had great intelligence, great wit, and great affection for us. He could move from the sublime to the ridiculous quickly. I felt a deepening appreciation of the title by which we called him: “Father.”

Then I went to Spain, University of Navarre in Pamplona, to finish classes and undertake a doctorate. I still thought I would return to the States as a layman. I attended a forty-day, intense Opus Dei program in the south of Spain. It’s a long seminar, like Tertio Millennio in Krakow. At the end, the director asked if I’d head a men’s residence at the University of Navarre, and I said, sure.

Dealing with the headaches and heartaches of all those guys touched a deep pastoral nerve, and moved me to think of becoming a priest. I consulted with St. Josemaría. He told me to pray about it and six months later, I told him I’d made the decision. I was ordained at the Basilica of St. Michael in Madrid in August 1973.

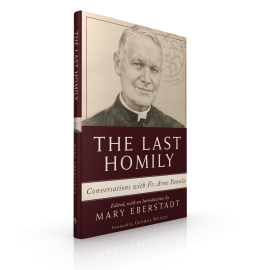

For her latest book, The Last Homily, noted author and speaker Mary Eberstadt spoke with the late Fr. Arne Panula of Washington, DC’s fabled Catholic Information Center. Her conversations with the beloved spiritual father range from sweeping discussions of art, history, and theology to everyday challenges like finding your vocation and thriving as a Catholic in a hostile culture.

You Might Also Like

The Last Homily captures with poignant authenticity the dying thoughts of a brilliant priest who dedicated his life to bringing others to God: Fr. Arne Panula, of Washington DC’s fabled Catholic Information Center.

The Last Homily captures with poignant authenticity the dying thoughts of a brilliant priest who dedicated his life to bringing others to God: Fr. Arne Panula, of Washington DC’s fabled Catholic Information Center.