By Madeleine Stebbins

Madeleine Stebbins is the author of Looking at a Masterpiece and Let’s Look at a Masterpiece: Classic Art to Cherish with a Child. These poignant works bring timeless truths to life through the beauty of art.

Piero della Francesca was born in approximately 1415 and died on the very day Columbus landed in America, October 12, 1492. Better known in his time as a mathematician and geometer, he is now recognized as one of the greatest artists of the early Renaissance.

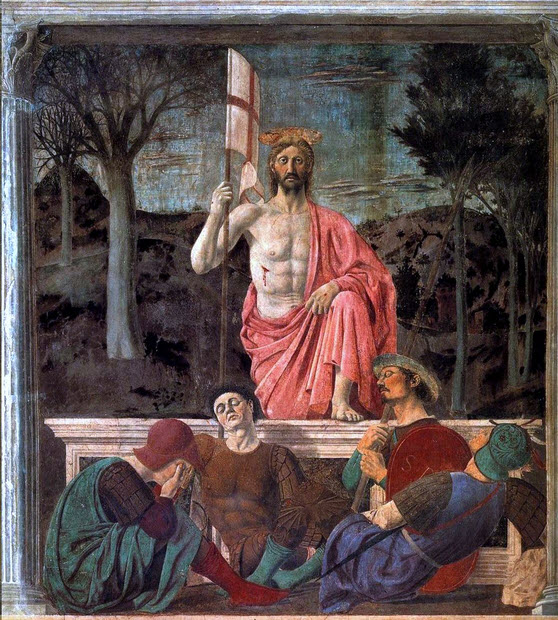

We see on the left of this fresco’s background a barren landscape and leafless trees, whereas on the right nature is blooming, symbolic of the world before and after the Resurrection. The act of redemption has been accomplished. Life is restored. The earth is transformed.

In the foreground leaning against the side of the sarcophagus are the sleeping guards, sluggish human beings, not yet awakened to the presence of God, two of them blinded by the divine light. The soldier in brown, center left, is reputed to be a self-portrait of the artist. The contrast between the practically lifeless guards and the fullness of life in the figure of Christ is striking and expresses the force of His supremacy over death.

The color of the Lord’s garment, no longer the scarlet blood-red of His martyrdom, is a beautiful rose: the liturgical color for joy. The wound in His side is still open. His blood is still flowing in eternity for our salvation.

Through a divine pedagogy, the Church in her liturgical year slowly reveals to us many aspects of the Holy Face of Christ. Since we humans are unable to grasp them all at once, we are shown the many facets one at a time. For instance: the infant Jesus, Christ the Good Shepherd, the Divine Mercy, the suffering Servant, and so on. What we see here is the image of Christ the Kyrios, the Lord of Lords in His supernatural strength, the Victor Rex—with sovereign power over life and death.

He who just a few hours ago had been like “a worm and no man” (Ps 22:6), wounded, bleeding, crushed to death, here miraculously comes forth out of the tomb like an athlete about to spring up with His muscular foot on the tomb. Unlike other depictions of the risen Lord which emphasize the ethereal quality of His glorified body, Piero della Francesca portrays Him as a conquering hero, physically risen, giving us a sense of His infinite power. He has an awesome majesty which forces us to our knees. He is the Rex tremendae majestatis.

The realization that this glorious God is also merciful Love is what has for centuries moved men and women to give their all to Christ. Through this masterpiece we begin to understand the great ancient Greek prayer of adoration: Ágios o Theos, Ágios íschyros, Ágios athánatos, eléison imas. Holy God, Holy mighty One, Holy immortal One, have mercy on us.

There is something breathtaking in this fresco. It pictures a seismic event. We get an astonishing sense of His presence and are directed upwards by the vertical rush out of the grave of Christ in the exact center with His banner of the victorious cross, the Vexilla regis, unfurled and held high. It is like the effulgence of a flame. His is the last word, the ultimate victory. We seem to hear a burst of trumpets. Yet at the same time there is a stillness.

His halo is a luminous crown, His eyes are all seeing, His gaze penetrating. There is a hieratic quality in His face and head, like an icon. He is sacred. He stands before us as “a bridegroom coming forth . . . as a giant to run his course” (Ps 19:5, Ps 18:6 Douay-Rheims).

Resurrexit sicut dixit. Alleluia.

You Might Also Like

What power does great art have? In Looking at a Masterpiece, the reader will discover the surprising answer—that great art can “influence our whole lives.” As author Madeleine Stebbins explains, “Great art deepens the soul, inspiring a thirst for greatness and purifying it of what is base. It opens our minds to a clearer perception of truth and our imaginations to a more radiant vision of moral goodness and nobility.”

What power does great art have? In Looking at a Masterpiece, the reader will discover the surprising answer—that great art can “influence our whole lives.” As author Madeleine Stebbins explains, “Great art deepens the soul, inspiring a thirst for greatness and purifying it of what is base. It opens our minds to a clearer perception of truth and our imaginations to a more radiant vision of moral goodness and nobility.”