As we begin the Easter season, the liturgy—particularly the lectionary readings—turn our attention to the Book of Acts. Here then I thought I’d return to some material I’ve touched upon here in the past, namely, the link between the Acts of the Apostles and the life of Christ in the Gospel of Luke.

Indeed, once you see how the ministry of the Church in Acts is linked to that of Christ’s in the Gospels—and the parallels are striking—you can never look at either book the same way again.

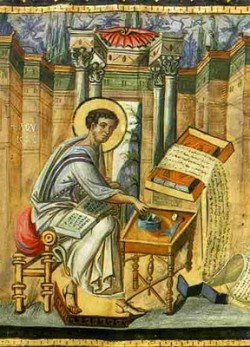

In the past I’ve explained that one of my favorite academic monographs on Luke-Acts is written by Charles Talbert’s, Literary Patterns, Theological Themes (1974).[1] Here I want to especially highlight the insights found in this work.

One more thing. . . This is going to be a multi-part series. If you like what you read here, please consider spreading it around; I’d appreciate it.

“Luke-Acts”

As most are aware, both the Gospel of Luke and the Book of Acts are attributed to Luke.[2] This is important. The two books are interrelated. Acts is a kind of sequel to the Gospel of Luke. The book relates the history[3] of the early Church beginning with Jesus’ ascension and ending with Paul’s preaching in Rome.

To interpret Acts correctly then one must really pay attention to the way to the two books form a kind of unified work. Scholars thus speak of “Luke-Acts”.

Luke-Acts as a Unity

The intended unity of Luke-Acts is clear simply from reading the introductions of the two books. Acts even refers the reader specifically back to the Gospel.

Luke 1:1–4: Inasmuch as many have undertaken to compile a narrative of the things which have been accomplished among us, 2 just as they were delivered to us by those who from the beginning were eyewitnesses and ministers of the word, 3 it seemed good to me also, having followed all things closely for some time past, to write an orderly account for you, most excellent The-ophilus, 4 that you may know the truth concerning the things of which you have been informed.

Acts 1:1–3: In the first book, O The-ophilus, I have dealt with all that Jesus began to do and teach, 2 until the day when he was taken up, after he had given commandment through the Holy Spirit to the apostles whom he had chosen. 3 To them he presented himself alive after his passion by many proofs, appearing to them during forty days, and speaking of the kingdom of God.

The similarities in the introductions are significant, e.g., both books are written to “Theophilus,” and play into the larger similarities between the two books I will discuss further down the road.

Here though let us notice a key element in the introduction to Act. Acts 1 explains the purpose of Luke as relaying “all that Jesus began to do and teach”. Richard Burridge puts it well: “. . . the description of the first book as ἤρξατο ὁ Ἰησοῦς, what ‘Jesus began to do and teach,’ suggests that Luke’s second volume recounts what ‘Jesus goes on to do and teach’ in the continuation of the same story.”[4] As we shall see, Acts, in a certain sense, shows us how Jesus continues his ministry in the life of the Church.

Why Do you Persecute Me?

The inseparable relationship of Jesus and the Church is highlighted in the story of Paul’s conversion. Saul/Paul, on his way to Damascus sees a great light and is knocked to the ground on the road. He hears a voice speaking to him: “Saul, Saul, why do you persecute me?” 5 And he said, “Who are you, Lord?” And he said, “I am Jesus, whom you are persecuting. . .” (Acts 9:4-5).

Note here Jesus’ exact words: “Why do you persecute me?” Saul could have easily answered, “I’m not persecuting you―I am going after your disciples.”

But such a protest would seem to miss the major theme Luke-Acts stresses: Jesus is to be identified with his Church. I think Paul reflected on the significance of these words his entire life. The ecclesiology of the Church as the Mystical Body of Christ seems to flow from reflection on this thought. As Paul says elsewhere, “I have been crucified with Christ; it is no longer I who live, but Christ who lives in me” (Gal 2:20).

Thus, as Christ lived in his earthly body, he now lives in the Church. What he did in his earthly body he now does in his Mystical Body. The ministry of the Church continues the ministry of Jesus.

As we shall see, these ideas are underscored throughout the book of Acts.

[To be continued!].NOTES

[1] Missoula: Society of Biblical Literature and Scholars Press, 1974.

[2] Some have tried to make a case that Luke should not be considered the author of the two works (cf. A.W. Argyle, “The Greek of Luke and Acts,” NTS 20 (1973–74): 441–45; J. Wenham, “The Identification of Luke,” EvQ 63 (1991): 3–44. I have discussed Martin Hengel’s work elsewhere regarding the authenticity of the superscriptions of the Gospel (see “Naming Names” near the bottom of this post). I am not going to rehash all that here. In sum, I see no reason to deny the unanimous testimony of the early church regarding Luke’s authorship of either the third Gospel or the book of Acts. In fact, truth be told, I think arguments against Lukan authorship fail on a number of grounds. Thus here I side with the vast majority of scholars who think Luke indeed is the author of both books. See the important convincing recent discussion in Darrell Bock, Acts (BECNT; Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2007). I largely agree with Bock’s conclusion: “In sum, the external evidence strongly favors Luke as the writer of Acts. That no other Pauline companion was ever put forward as the author of this work when many such candidates existed is key evidence. It is true that the internal considerations and theological emphases raise questions about whether Luke is the author; but not to a degree that cancels out the likelihood that he was the author and that the tradition has the identification correct.” I might add here that the given the strong evidence favoring the authenticity of the superscription of Luke’s Gospel, the “internal” evidence is far less ambiguous than even Bock suggests here. Other scholars who favor Lukan authorship include, e.g., Martin Hengel, Between Jesus and Paul: Studies in the Earliest History of Christianity (London: SCM, 1983), 97–128; F. F. Bruce, The Book of Acts (rev. ed.; NICNT; Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1988), 7. See also the fuller bibliography in A. Wikenhauser and J. Scmid, Einleitung in das Neue Testament (6th ed.; Freiburg im B.: 1973).

[3] Here I will not give a long discussion on the genre of Acts. I side with those who have argued―I think rather definitively―that the work should be classified in the genre of Greco-Roman history, though it certainly has certain overlaps with other kinds of writing. Again, the most recent discussion offered by Bock (Acts, 1–3) should be consulted by those interested in learning more.

[4] Richard Burridge, Imitating Jesus: An Inclusive Approach to New Testament Ethics (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 2007), 228.