By Leroy Huizenga

Leroy A. Huizenga is Administrative Chair of Human and Divine Sciences at the University of Mary in Bismarck, ND. He is the author of Behold the Christ: Proclaiming the Gospel of Matthew.

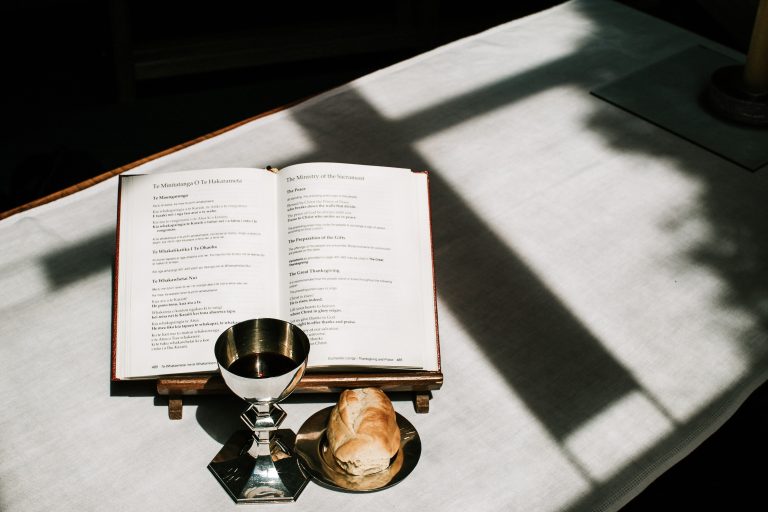

For Catholics, Scripture is embodied not merely in our lives but also in liturgy. Indeed, it’s embodied first in liturgy, from the Mass to private devotions, and that’s where we find our formation.

Reading Scripture, then, isn’t simply a matter of seeing how the New Testament fulfills the Old. For much of Protestantism, the New Testament fulfills the Old, and then, the meaning of the Bible having been determined, the preacher delivers it as content. But for Catholicism, the New Testament fulfills the Old; then Jesus Christ, who is the fulfillment of the Old, delivers himself in the Eucharist. Just as the Israelites and Jews performed liturgies that Jesus himself performed, fulfilled, and transformed, the Church, in imitation of and obedience to Jesus, performs the liturgy of the Eucharist, the Mass.

A liturgical approach to the realization of Scripture is no Catholic imposition left over from the middle ages but is consonant with the canon itself. For from Genesis to Revelation, liturgy dominates Scripture. Consider the following:

The Garden of Eden is a temple—because the presence of a god or God makes a temple in the ancient world—with Adam as priest; thus the later Israelite temples were designed to reflect Eden, with the priesthood fulfilling the role of Adam (and of course Jesus Christ, the new Adam, is the great high priest). And as evangelical scholar Gordon J. Wenham observes:

“Genesis is much more interested in the cult than is normally realized. It begins by describing the creation of the world in a way that foreshadows the building of the tabernacle. The garden of Eden is portrayed as a sanctuary decorated with features that subsequently adorned the tabernacle and temple, gold, precious stones, cherubim, and trees. Eden was where God walked . . . and Adam served as priest.

Genesis then later presents other significant figures offering sacrifices at significant moments, among them Abel, Noah, and Abraham. Moses commanded Pharaoh to let the Hebrew people go so that they might worship: “Thus says the Lord, the God of Israel, ‘Let my people go, that they may hold a feast to me in the wilderness’” (Exod 5:1b). Much of the Pentateuch, the five books of Moses, concern liturgy and sacrifices, especially from the last third of Exodus through Deuteronomy. The books of history are marked with sacrifices. The Psalms were sung in sacrificial liturgy. And the prophets weren’t opposed to sacrificial liturgy as such, but wanted the people to live righteous lives, lest their sacrifices be hypocritical (the idea that the prophets were resistant to the sacrificial priesthood comes from Protestant scholars of the nineteenth century reading their own opposition to the Catholic priesthood back into the texts). Ezekiel himself was a priest, and Isaiah foresaw the Gentiles bringing their sacrifices to Zion at the end of time (Isa 56:6–8).

In the New Testament, Jesus institutes the sacrificial ritual of the Eucharist. In Acts, the early Christians attend services in the temple while they also devote themselves to “the apostles’ teaching and fellowship, to the breaking of bread and the prayers” (Acts 2:42). In 1 Corinthians 11, St. Paul spills a good amount of ink dealing with propriety in the Eucharistic liturgy. Hebrews is a long argument for the superiority of the Mass to Jewish sacrifices. And the Book of Revelation is less about the horrors of the end times and much more about the eternal liturgy of heaven; as such, it’s primarily been used as a pattern for liturgies on earth.

Further, believers throughout history have encountered Scripture primarily in liturgy. From the ancient world until perhaps the sixteen hundreds, five or maybe ten percent of the population could read. And so Israelites, Jews, and Christians would hear the Bible read in worship, in the temples, synagogues, and churches. In fact, the driving question that led to the formation of the New Testament canon was not “Which of these documents were inspired?” As the early Church sorted through writings, from the Gospel of Mark to Third Corinthians, from 2 John to the Acts of Paul and Thecla, from Hebrews to the Gospel of Peter, the question was “Which of these documents may be read in the Church’s liturgy?” The early Church did so by asking which documents came from the Apostles and reflected the apostolic Faith, which they did to determine what could be read and preached in the Mass.

So what does that look like? It’s a three-stage process, involving the Old Testament, the New Testament, and the Church’s liturgy. The Old Testament foreshadows and prefigures the events of the New, and so the New in turn fulfills the events of the Old. Unlike Gnosticism, which splits the Old Testament from the New and sees different gods superintending each, Catholics operate with the conviction that the same God superintends both Testaments, which together tell the salvific story from creation to consummation.

You Might Also Like

Behold the Christ: Proclaiming the Gospel of Matthew, by Leroy A. Huizenga, reveals the significance of St. Matthew’s Jesus: He is Emmanuel, God with us always, who saves his people from their sins by dying for them. Keyed to the lectionary and featuring a section on the relevance of St. Matthew’s Gospel for our contemporary age, Behold the Christ will make the Gospel and indeed the Faith real to today’s readers.