By Jacob Wood

The word “sacrament” comes from a Latin word, sacramentum. In ancient Rome, sacramentum was a legal term. It referred to a bond you posted at the beginning of a lawsuit as the proof of your good faith that you would pay the judgment if you lost. By extension it also referred to the oath you took at the beginning of military service, which is itself a pledge of good faith. But for the Romans, taking an oath to enter military service was not just a pledge of good faith; it was also a religious commitment. By the time of Caesar Augustus, many Romans thought that the Roman emperor was a god, and the worship of the emperor became an official part of Roman life. When a man entered the emperor’s service, the Romans considered it a permanent religious commitment; the man received a branding with a hot iron as a permanent mark of that commitment.

The early Church writer Tertullian seems to have been the first person to sense the similarity between the words that Jesus gave to the Church and the words professed by Roman soldiers upon entering the emperor’s service. Not that there is any similarity between God and the Roman emperor—the imperial cult was idolatrous!—but both sets of practices involve the profession of words which began a person’s entrance to a new community and a new way of life (Adversus Marcionem 4.34).

However great the similarities between God’s words and the Roman military oath may have been, Tertullian was very careful to emphasize the differences. He thought that the kind of service to the emperor required by the Roman sacramentum was absolutely incompatible with the service that Christians owe to God alone (De corona militis 11), and that even though other religions have their own rites involving life-changing words and commitments to new forms of life, none of them possess the truly transformative power of the words that God speaks in the sacraments of the Catholic Church (De praescriptione haereticorum 40).

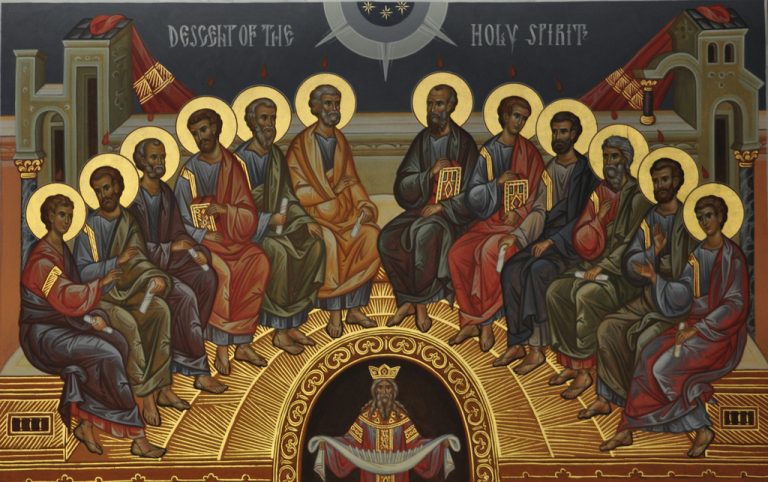

It was St. Augustine who best articulated the difference between the sacraments of the Church and the customs of Roman soldiers (De baptismo 3.16.21). The transformative power behind the sacraments of the Catholic Church, he observes, is the Holy Spirit—the same Holy Spirit who hovered over the waters at creation when God spoke the words of creation (Gen 1:2), overshadowed Mary when the Word of God was Incarnate in her womb (Lk 1:35), who is “poured into our hearts” when we are united to friendship and fellowship with God (Rom 5:5), and who bestows upon those who are united in friendship and fellowship with God “the unity of the Spirit in the bond of peace” (Eph 4:3). Only those who belong to that unity—outwardly or by desire—receive the Holy Spirit, because Jesus entrusted that Spirit to his Church (De baptismo 1.2.3; Jn 16:13, 20:22; Acts 1:8; CCC 846–848). Even though the sacraments of the Church have certain similarities to secular rites of passage and the ceremonies of other religions, no other words give us the Holy Spirit like those of the seven sacraments.

St. Augustine was also one of the first Church Fathers to articulate very clearly why the Holy Spirit makes such a difference. It is because the Holy Spirit gives us grace. “Grace is favor, the free and undeserved help that God gives us to respond to his call to become children of God, adoptive sons, partakers of the divine nature and of eternal life” (CCC 1996). In giving us his grace, God helps us to come closer to him in two ways. Sometimes he intervenes in our lives in a special, more immediate way—like when we sin and he wants to call us back to himself, or when he wants us to take a big step in the spiritual life like embracing a vocation to religious life, the priesthood, or marriage. In those situations, we say that God gives us actual grace, because the grace he gives us makes us act. Other times, after we have acted on the graces that God has given us, he intervenes in our lives in a stable, more permanent way—like when he strengthens us in faith after baptism, or in love after marriage. In those situations, we say that God gives us habitual grace, because he causes a habit in us—a stable disposition (St. Thomas Aquinas, Summa theologiae, Ia–IIae, q. 49, a. 1). The greatest of all habits we call sanctifying grace. “Sanctifying grace is an habitual gift, a stable and supernatural disposition that perfects the soul itself to enable it to live with God, to act by his love” (CCC 2000). The goal of sanctifying grace is the complete transformation of our souls so that we may “become partakers of the divine nature” (2 Pet 1:4; CCC 1129).

Dr. Jacob W. Wood is Assistant Professor of Theology at the Franciscan University of Steubenville. He has presented at conferences nationally and internationally. He is the author of Speaking the Love of God: An Introduction to the Sacraments.