The Lamb's Supper: The Bible and the Mass

Lesson Six: Memory and Presence: Communion as the Coming of Christ

Lesson Objectives

- To understand the deep biblical foundations of Jesus’ command that the Eucharist be celebrated “in memory of Me.”

- To see how Scripture portrays Jesus as the Passover Lamb and how that portrayal is reflected in the Mass.

- To understand the Eucharist as parousia, the “coming” of Christ, and as the “daily bread” we pray for in the Our Father.

III. At the Lamb's Supper

A. Giving Us Our Daily Bread

From these texts we can understand the tradition handed on to us by the apostles - that Christ is "our paschal lamb" (see 1 Corinthains 5:7) whose blood was shed for our salvation and whose flesh and blood we eat and drink in remembrance of that salvific act.

We profess this faith in every Mass, making the words of Scripture our own.

The priest presents the consecrated bread to us with John's words: "Behold the Lamb of God who takes away the sin of the world" (see John 1:29).

He follows these words with words drawn from John's Revelation, which allude to the wedding supper of the Lamb ("Happy are those . . . " see Revelation 19:9).

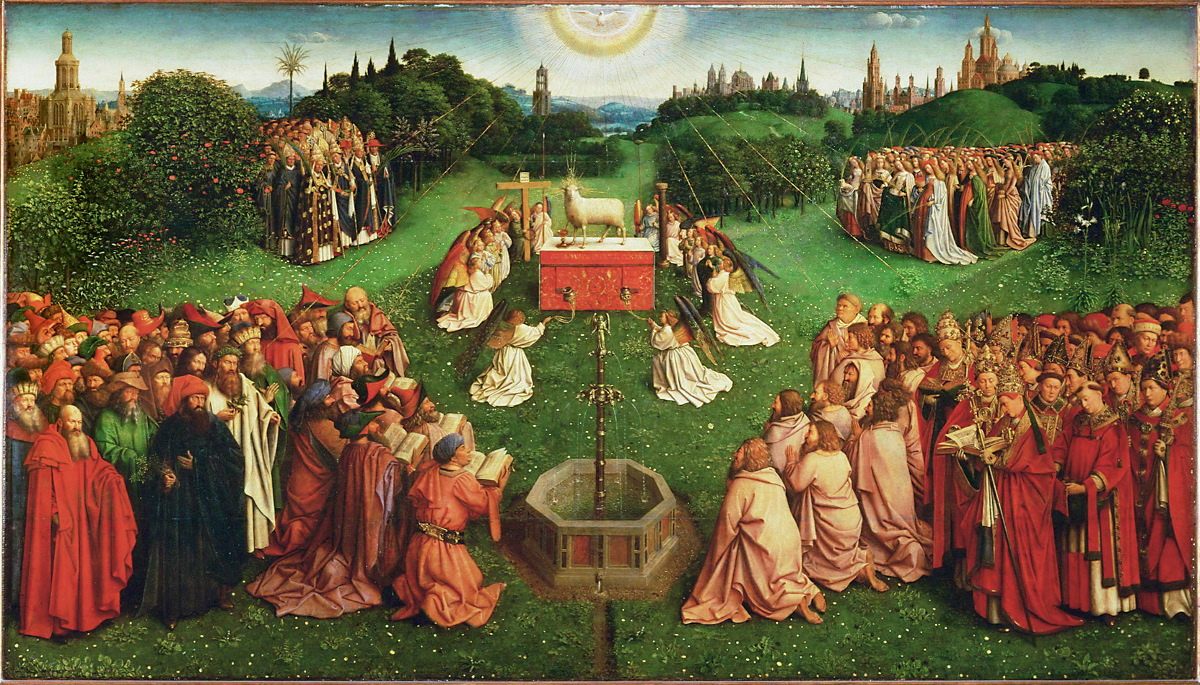

As we explored in Lesson 5, in the Eucharist we join ourselves to a cosmic liturgy, described in Revelation as a heavenly wedding feast.

As is appropriate for a wedding feast, we introduce the Communion Rite of the Mass by praying the family prayer that Jesus taught us (see Matthew 6:9-13;Luke 11:2-4).

In the context of the Mass, the petitions of the Our Father take on new meaning. We might even say that the Mass fulfills the Lord's Prayer word for word.

In the Mass, we hallow or glorify His name and ask Him to forgive our trespasses. The Sign of Peace symbolizes our forgiveness of those who've trespassed against us - as we offer a gesture of reconciliation before approaching he altar (see Matthew 5:23-24; John 14:27).

In the Mass, the Father gives us our "daily bread." In fact, epiousios, the word translated "daily," is a Greek word found only in the Lord's Prayer. It's exact meaning has puzzled translators and scholars for more than 20 centuries now.

It's interesting to note, however, that the idea and expression "to give bread" seems to trace back to the primordial experience of God giving the Israelites a daily portion of bread from heaven as they sojourned in the wilderness (see Exodus 16:4; Psalm 78:24).

The giving of bread becomes an image of God's care and salvation elsewhere in the Old Testament (see Psalm 107:9; 146:7; Proverbs 30:8-9).

Jesus refers to the original wilderness experience in His Passover sermon at Capernaum - saying that our "Father gives you the true bread from heaven" (see John 6:32).

The idea of giving bread occurs only in a few other places in the Gospels. But those places are all highly suggestive. In fact, each time it appears, it is in a scene heavy with Eucharistic overtones.

Jesus takes, blesses, breaks, and gives bread in His miraculous multiplication of the loaves (see Mark 6:41; 8:6; Matthew 15:36; John 6:11); at the last supper (see Mark 14:22;Matthew 26:26); and at Emmaus after His resurrection (see Luke 24:30).

So, too, in the Mass, he comes to give us our daily bread. By this bread we are strengthened against temptation, and promised deliverance from evil.

In the Mass, we're blessed to be able to eat bread in the kingdom of God, as Jesus promised (see Luke 14:15). Indeed, in the cosmic liturgy of the Eucharist, the kingdom has come on earth as it is in heaven.

That's why the early Christians recited a short "doxology" after saying the Lord's Prayer during the Mass. We still pray their doxology ("For the kingdom, the power, and the glory . . . ") in our Mass.

B. Until He Comes Again

In the earliest Eucharistic celebrations, the first believers also prayed a short prayer for the coming of the Lord in glory: "Come, Lord Jesus!"

The prayer - an Aramaic expression, Marana tha - is also found in the New Testament where it also evokes the Eucharistic setting (see 1 Corinthians 16:22; Revelation 22:17, 20).

The early Christians looked forward to the second "coming" of the Lord. The Lord's coming in glory was anticipated as a time when He would finally reveal himself and call all peoples into His presence for judgment (see Matthew 24:27; 1 Thessalonians 2:19; 3:13; 2 Thessalonians 2:1,8; 1 John 2:28).

Parousia (pronounced: PAHR-oo-SEE-uh), the Greek word used by the New Testament writers for this "coming," means both "advent" or "arrival" and "bodily presence." For instance, Paul uses parousia to describe his own immediate bodily presence, which he admits is, while real, not striking or imposing (see 2 Corinthians 10:10; Philippians 2:12).

Outside the Bible, parousia came to be an official term for the visit of a king or emperor.

And the first Christians saw the Eucharist as a parousia.

"For as often as you eat this bread and drink the cup, you proclaim the death of the Lord until He comes," Paul wrote (see 1 Corinthians 11:26).

Paul's words are still heard in our Eucharist celebrations today - one of three options for proclaiming the Mystery of the Faith following the consecration of the bread and wine.

Very early, Christians began praying, as we still do, "Hosanna . . . blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord" in their celebrations of the Eucharist (see Matthew 21:9).

Jesus himself had said, on the threshold of His passion: "I tell you, you will not see me again until you say, 'Blessed is he who comes in the name of the Lord'" (see Matthew 23:39).

And we see Him when we say this prayer in the Mass. In every Eucharist, He fulfills His promise to be with us until the end of the age (see Matthew 28:20).

The Eucharist is His coming, the parousia, the Real Presence of Christ. In the Eucharist we have the bodily presence of Christ, the coming of the king who stands at the right hand of God (see Acts 7:56).

In describing His "coming," Jesus said that "this generation will not pass away until all these things have taken place" (see Matthew 24:34).

And at the last supper, He said He would not drink wine "until the kingdom of God comes" (see Luke 22:18).

A moment later, He told the apostles: "I confer a kingdom on you . . . that you may eat and drink at my table in my kingdom, and you will sit on thrones judging the twelve tribes of Israel" (see Luke 22:29-30).

These same images are found in John's vision of the cosmic liturgy - the wedding feast of the Lamb (see Revelation 19:9); Jesus as the Word of God and the King of Kings (seeRevelation 19:13,16); the kingdom of priests who reign with him (see Revelation 5:10;20:6); the thrones of judgment (see Revelation 20:12); the "apostles of the Lamb" and the "twelve tribes of the Israelites" (see Revelation 21:10-14).

C. A Share in His Body and Blood

Whenever the New Testament speaks of Christ's coming, it speaks also of His judgment. The Eucharistic parousia is a real presence - Christ coming in power to judge.

This is why we must come worthily to the celebration. As Paul warned, if we do not come worthily, we eat and drink judgment upon ourselves (see 1 Corinthians 11:27-32).

This is why before we pray the words of the centurion while on our knees before receiving communion, "Lord, I am not worthy . . . " (see Matthew 8:8).

We are not worthy to be visited by our Lord. And yet He makes us worthy. He grants us "participation" (koinonia, "communion" or "sharing") in His body and blood (see 1 Corinthians 10:16). Through this Eucharist we "come to share (koinonia) in the divine nature" (see 2 Peter 1:4).

This participation, this sharing, is the goal of all of salvation history, the blessing that God desired to bestow on all peoples. It is a history that begins "in the beginning," as we read on the Bible's first page, and continues in every Mass, in which we echo the prayer found on the Bible's last page - "Amen! Come, Lord Jesus!" (see Revelation 22:20).

And with every coming of the Lord in the Eucharist we anticipate that final coming, when death will be defeated, and He will hand over the kingdom to His Father, and God will be all in all (see 1 Corinthians 15:23-28).

In the Eucharist we receive what we will be for all eternity, when we are finally taken up to heaven to join with the heavenly throng in the marriage supper of the Lamb. At Holy Communion we are already there.

"The Lord is with us," as the priest says after communion. And we are sent away from every Mass in peace - both dismissed and commissioned - to live the mystery, the sacrifice we have just celebrated, through the splendor of our ordinary life in the home and in the world.

Other Lessons

- Lesson One: A Biblical Introduction to the Mass

- 1. To understand basic Catholic beliefs about the relationship between the Bible and the Liturgy.

- To understand the biblical basis for the Mass.

- To understand how in the Mass, the written text of the Bible becomes Living Word.

- Lesson Two: Given for You - The Old Testament Story of Sacrifice

- To understand the biblical background to the Penitential Rite and the Gloria in the Mass.

- To understand how God is worshipped in the Old Testament.

- To understand the biblical notion of sacrifice as it is presented in the Old Testament.

- Lesson Three: One Sacrifice for All Time

- To understand the death of Jesus Christ on the cross as a sacrifice.

- To see the parallels between the Old Testament sacrifices and the sacrifice of Christ on the cross.

- To understand how that sacrifice is re-presented to us in the Mass.

- Lesson Four: Fulfilled in Your Hearing: The Liturgy of the Word

- To understand Scripture as the living Word of God.

- To understand the place of Scripture at the center of the liturgy.

- To see Scripture as an encounter with Christ, the living Word of God.

- To see how the Liturgy of the Word prepares us for the Liturgy of the Eucharist.

- Lesson Five: Heaven On Earth: The Liturgy of the Eucharist

- To understand the deep biblical foundations for the Liturgy of the Eucharist.

- To see how the Book of Revelation describes the liturgy of heaven.

- To understand how the Mass we celebrate on earth is a participation in the liturgy of heaven.