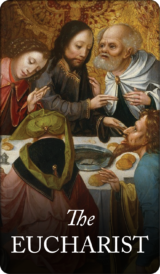

Did Judas Receive the Eucharist at the Last Supper?

By Clement Harrold

Catholic doctrine clearly teaches that a person in a state of mortal sin must not receive Holy Communion. As the Catechism of the Catholic Church explains, “The Eucharist is not ordered to the forgiveness of mortal sins - that is proper to the sacrament of Reconciliation. The Eucharist is properly the sacrament of those who are in full communion with the Church” (#1395).

This principle is itself rooted in the New Testament, drawing on the Apostle Paul’s injunction to the Corinthian church: “Whoever, therefore, eats the bread or drinks the cup of the Lord in an unworthy manner will be guilty of profaning the body and blood of the Lord” (1 Cor 11:28).

But this presents a conundrum for faithful Catholics when considering the case of Judas Iscariot. Although some of the Gospel accounts are ambiguous (Mt 26:20-29; Mk 14:17-25; Jn 13:21-30), the Gospel of Luke seems to indicate that Judas received Holy Communion in the Upper Room:

19 And he took bread, and when he had given thanks he broke it and gave it to them, saying, “This is my body which is given for you. Do this in remembrance of me.” 20 And likewise the cup after supper, saying, “This cup which is poured out for you is the new covenant in my blood. 21 But behold the hand of him who betrays me is with me on the table. 22 For the Son of man goes as it has been determined; but woe to that man by whom he is betrayed!” (Lk 22:19-22)

Judas was apparently still at the table following the institution of the Eucharist, and so we can presume that he received the Sacrament along with the other disciples. But if (as seems likely) Judas received the Eucharist in an unworthy manner, why then did Jesus do nothing to prevent it?

Over the centuries there have been several different approaches to this question. The first, favored by Church Fathers like St. Hilary of Poitiers and St. Ephraim the Syrian, is to attempt to read the Gospel accounts in such a way as to argue that Judas did not in fact receive the Eucharist. The problem with this approach, as we have seen, is that it seems to contradict a straightforward reading of Luke’s Gospel.

Another possible solution has been to concede that Judas received the Eucharist, but propose that he did so legitimately because he had already repented of his betrayal in his heart. Proponents of this view point to Matthew 27:3-5, where we are told that Judas repented and returned the thirty pieces of silver to the priests and elders, before going off to hang himself. An obvious problem with this interpretation, however, is that Matthew’s Gospel clearly describes Judas’s repentance as occurring after the Last Supper had taken place. In fact, Judas travels directly from the Upper Room to meet up with Jesus’s arrestors, so it is hard to argue that he experienced any real remorse during the Last Supper.

That leaves one final explanation, defended by the likes of St. Augustine of Hippo, St. John Chrysostom, and St. Thomas Aquinas. For these thinkers, the correct understanding is that Judas did receive the Eucharist at the Last Supper, and this was something which Jesus allowed because the betrayer’s sin was not yet public. As Aquinas explains in the Summa theologiae, “[I]t was not in keeping with His teaching authority to sever Judas, a hidden sinner, from Communion with the others without an accuser and evident proof” (ST III.81.2).

For Aquinas, the important principle here is that priests cannot read souls, and it would be unjust of them to publicly “out” a secret sinner by denying Holy Communion. Certainly the priest could try to dialogue with that person behind closed doors, but in the case of private or hidden sins, the individual’s decision to receive the Sacrament remains (to some extent) between them and God.

If a priest were driving past an abortion clinic and saw one of his parishioners walking in the door, that would not in itself be grounds for the priest to publicly deny them Holy Communion the next time they go to Mass. Certainly, if the parishioner had participated in an abortion, then he or she would have a grave obligation to refrain from Communion until receiving sacramental absolution. But the point is that, because the sin was committed in private, the responsibility of enforcing that obligation would fall on the parishioner, and not on the priest.

Jesus could read souls of course, but His purpose at the Last Supper, according to Aquinas, was to provide an example for how ordinary priests are supposed to act: “Consequently, Christ did not repel Judas from Communion; so as to furnish an example that such secret sinners are not to be repelled by other priests.” So it seems that Judas did receive the Eucharist at the Last Supper, and Jesus tolerated it because Judas’s sin had not yet been made public.

This underlines an important point, which is that in cases where individuals are living in a public state of grave sin—for example, when a Catholic politician repeatedly and publicly expresses support for abortion—then the Church is obliged to deny them Holy Communion until they have repented of their actions (see Code of Canon Law #915). In a situation such as this, the priest administering Holy Communion is not attempting to read the person’s soul or somehow expose them as unworthy; rather, the priest is denying them the Sacrament on the basis of their public misdeeds, in order to safeguard the Church’s teachings and avoid scandalizing his flock.

The tragic case of Judas should serve as a cautionary tale to all of us in the way we approach the Holy Eucharist. It was the Bread of Life discourse at Capernaum which first caused Judas to falter in his faith (see Jn 6:66-71), and it was right after he received the Eucharist unworthily that Satan entered into him (see Jn 13:27). We should therefore pray earnestly for the gift of faith that enables us to embrace this mystery more fully, and to approach the Sacrament with all due reverence and humility.

Clement Harrold is a graduate student in theology at the University of Notre Dame. His writings have appeared in First Things, Church Life Journal, Crisis Magazine, and the Washington Examiner. He earned his bachelor's degree from Franciscan University of Steubenville in 2021.

You Might Also Like

Delve deeper into the Blessed Sacrament with this Emmaus Academy course on the Eucharist by Dr. Lawrence Feingold. This course explores the fittingness and purpose of the Eucharist, highlighting its three fundamental aspects: presence, sacrifice, and communion. Beginning with an examination of biblical sources and writings of the Church Fathers, the course delves into the Real Presence and the controversy surrounding it, followed by an exploration of the sacrificial dimension of the Mass and the roles of the ministerial and common priesthood.

Watch now with an All Access membership or free trial of Emmaus Academic.