What many people fear in death, whether their own or that of those they love, is the loss of connection with their loved ones. If we think of going to heaven as though it were like going to Cleveland (only better), then we are sad that they or we are “going away,” even if we hope it is a “better place.” But if heaven is union with the Father in Christ through the Spirit, and if Christ lives and is present to each of us, then we, too, remain connected with our loved ones—even more intimately and fully—in union with Christ’s Body and the communion of saints. We believe that Christ lives and that he continues to watch over us, sending his Holy Spirit to guide and strengthen us. When those we love were alive, we sometimes asked them to pray for us, knowing they would precisely because of their love for us. The Christian promise is that this sort of love can never die (see Rom 8:38). It lives on in Christ.

To the extent that our love is selfless and true and directed toward the good of the other person, then it is from God and of God, and, as St. Paul assures us, nothing can separate us from it. And note, we do not love merely with our own imperfect love. Indeed, whatever had been lacking in the justice or goodness of that love is purified in our union with God. We love with God’s perfect love, not merely with our own imperfect love. Our descendants need ask only whether what they do is in accord with God’s will, not whether it would have been in accord with the limited, imperfect standards we held during life. For if they do God’s will, they will be satisfying the perfected love of all those united with God in the communion of saints.

Entering into a heavenly union with God does not mean I can now love only God any more than becoming a Christian means I can no longer love my wife and my children. Those particular embodied connections are a foretaste of the communion of the saints. Christ’s Resurrection reveals and makes it possible that those who have died are still connected to us and we to them. We are not merely loving a ghost or a memory. Christ is risen and so are all those who are “members” of his one Body. When we love him, and them in him, we are loving a living person who is now living more truly because he or she is not living a life in the shadow of death; they are not living a life that runs down and runs out. For them, life is not merely the passage of time or mere survival. It is unbounded love, no longer bound by the restrictions of time and space, just as the risen Christ was no longer bound by the restrictions of time and space. He appeared to Apostles bodily in the Upper Room; they touched him and ate with him even though the doors and windows were closed and locked. And he remains just as present to us now, even centuries later.

Catholics believe that they can pray to St. Francis and St. Thomas Aquinas because they believe those saints are still alive in Christ, still loving us and praying for us. The citizens in Italy and Assisi can have a special devotion to St. Francis because his connection to the place of his birth and to the people to whom he was sent has not lessened. He is not less the saint of Assisi now than he was when he was alive. And yet I know that his love, connected as it is through Christ to the Holy Trinity, is now extended to me as well even though I live on another continent centuries after his death. When I embrace the spirit of poverty and refuse to be mastered by my ownership of things, St. Francis is alive in me. When I sit down to write and ask St. Thomas for his guidance, he prays for me. I can participate in the same Spirit of wisdom and love that animated him.

Certain developments in modern science can tempt us into thinking that the universe is empty. More recent research has shown that it is far from empty. Amazing things are happening in that realm we call outer space, which we used to think was cold and empty, So, too, on the Christian account, the universe is full in other ways too, beyond what we can directly observe or measure. It is full of angels and seraphs and the spirits and souls of the just, all of whom are looking out for us, rooting for us, praying for us, and encouraging us. It would not be completely inaccurate to say that we have, each of us, an immensely large cheering section on our side, working and praying for our salvation and well-being. Not only beloved grandmothers and dead uncles but also people we never even knew existed. United with Christ in his risen Body, they are with us, as Christ is with us, in every moment of our lives, especially when we are weak or suffering and in special need of their help and guidance.

We need to pray for them and ask them for their prayers for us. Then we should try to remain aware of all those who are united with God and the saints and look for evidence of their continuing blessings in our lives. We “pray” to them only in the sense that we ask for them to pray for us to the Father, to whom they are united by being united to Christ. We pray, first, because prayer is invaluable for its own sake but also so that we become, even now, persons we hope eventually to become: saints—those who love and pray to the Father in Christ “unto the ages of ages,” in saecula saeculorum, for the redemption of all mankind and all creation.

We should not think of heaven, therefore, primarily as just a place—as though dying and going to heaven was something like losing your job and having to leave your friends and move to a different city where you don’t know anyone. Heaven is a loving communion of persons. You enter into an eternal communion of Trinitarian love. And just as entering into a loving communion of persons here on earth changes you and challenges you to become more than you ever dreamed possible, so too, in union with the Father, Son, and Spirit and the communion of saints in communion with them, you do not love this world less; you love it more, in ways that transcend our current limitations of time and space.

Christianity is a very fleshy religion, a characteristic that has often in history made it seem absurd to those with a gnostic spiritualist bent. Christianity, in accord with the Jewish creation account, affirms that the material world is “good,” indeed “very good.” The Christian creed includes the affirmation that the Word became flesh in the Incarnation of God’s Son. And the risen Christ reveals an afterlife in which we will enjoy a bodily resurrection. Properly understood, then, the Christian view of the life after death would not cause one to diminish the value of the human body or, by extension, of our other material connections in this life, especially our connections to other people and the particular communities into which we are born or to whose good we have devoted ourselves. As St. John Paul II emphasized in his “theology of the body,” our communion with others is achieved in and through the body. The Christian teaching about the resurrection of the body assures us that we will not be denied the benefits of our bodily existence after death. As we said above, nothing good in this world could possibly be absent from God, who is the Source of all goodness. The senses are functions of a body. Feeling the softness of skin or the warmth of a hot shower, tasting the sharp, somewhat bitter combination of salt and tequila in a margarita or the musky flavor of some barbequed ribs, smelling the wonderful aroma of cinnamon and apple baking in a pie—all these depend on having a body. Ghosts don’t hug (as Odysseus found out when he attempted to embrace his mother) or kiss or eat sizzling fajitas or take hot showers.

But the way we are embodied at present in this life has limits. When we are with our friends in New York, we cannot be with our friends in San Francisco. And when we are with our beloved grandparents, we usually cannot also be with our beloved grandchildren. We are limited by time and space. To be free of those restrictions, but not as a ghost or a memory, is the promise of the glorified body. It is the promise Christ shows us when he reveals himself to the women at the empty tomb and the disciples on the road to Emmaus and to the Eleven in the locked Upper Room. It is the promise realized every day around the world when the one crucified, risen Christ makes himself present in the Eucharist in Chicago and Lima and Tokyo and St. Petersburg and Berlin and Abuja, in cities and hamlets around the world, as he has been doing for centuries and will do until the end of time.

RANDALL B. SMITH is Professor of Theology at the University of St. Thomas in Houston, Texas. He received his B.A. in Chemistry at Cornell College, an M.A. in Theology at the University of Dallas, and his M.M.S and Ph.D. Medieval Studies and Philosophy at the University of Notre Dame under the direction of Ralph McInerny. He is the author of Reading the Sermons of Thomas Aquinas: A Beginner’s Guide and Aquinas, Bonaventure, and the Scholastic Culture of Medieval Paris. He writes regularly for The Catholic Thing.

You Might Also Like

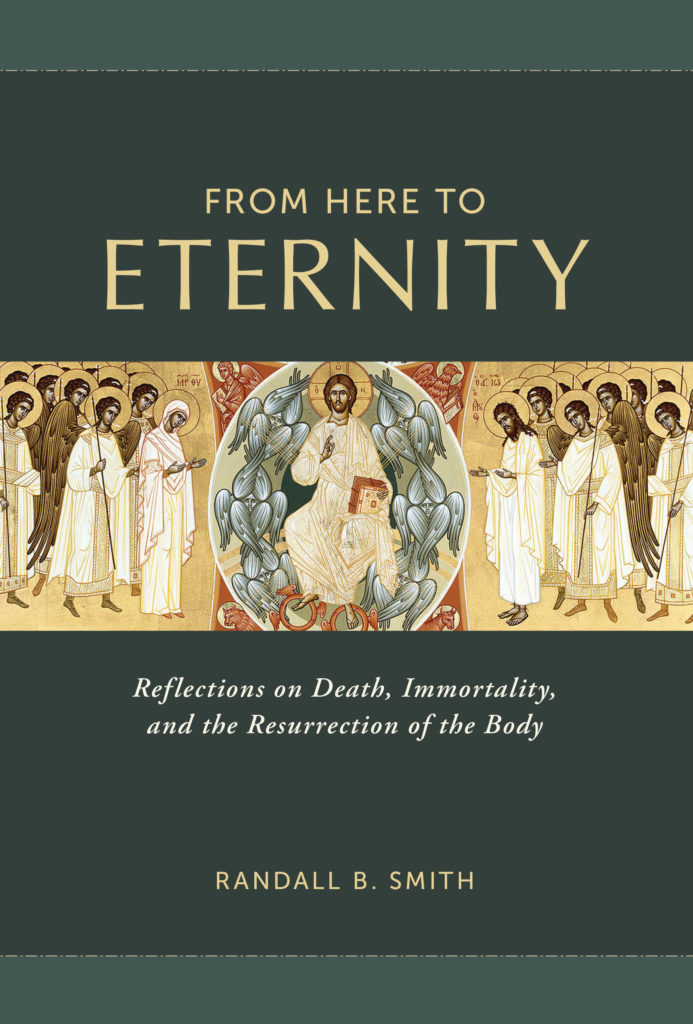

Throughout history and across cultures, people have shared the hope and the belief that somehow something about the human person survives death. Indeed, it seems that without a notion of life-after-death, this life would seem meaningless. If, in the end, everything we have strived for and all our love comes to naught and is simply swallowed up by nothingness, then what was the point of it all? In From Here to Eternity, Randall Smith shows how the Christian doctrines regarding the resurrection of the body and the communion of saints provide an understanding of life after death as a meaningful fulfillment of this life, not a negation of it.