Holy Mass is an opportunity every day to make a decisive act of faith. Jesus said, “My flesh is food indeed, and my blood is drink indeed” ( John 6:55). Did he mean it or not? Do we believe him or not? An impartial reading of that text shows that Jesus emphatically meant what every Christian for fifteen centuries understood he meant: that the Eucharist truly is his Body and Blood. If that is not true, then our whole religion is a sham. We are the greatest of fools. But if it is true, then it is insanity not to order our lives around it.

We are, then, confronted with a choice. The doctrine of the Real Presence does not admit of any middle ground. The sacred Host cannot be almost Jesus’ Body and Blood, any more than your physical presence is almost you. The teaching is a direct challenge to the dogmatic materialism of our age since there is no room to wriggle out of the choice. Unless the Eucharist is purely symbolic—which does obvious violence to the words of Jesus—then it is Jesus himself. Reflecting on one of the great Cathedrals of Europe, Mary Eberstadt pointed out that “nobody builds this for a piece of bread.”

John’s Gospel drives the point home by reporting that the disciples of Jesus deserted him after his Eucharistic sermon in the synagogue of Capernaum. “This is a hard saying; who can listen to it?” ( John 6:60). And then Jesus turns to his apostles and asks quietly, insistently, “Will you also go away?” (John 6:67). At that moment, they had a choice to make, just like us.

If the Eucharist is true, everything is different—how we worship God, how we treat each other, how we brush our teeth. St. Mary Elizabeth Hesselblad was born into a Swedish Lutheran family. Once when visiting some friends in Brussels, she accompanied them to a Corpus Christi procession at St. Gudula Cathedral. As the bishop was approaching with the Blessed Sacrament, every one began to kneel and Mary Elizabeth moved back so as not to offend others by not kneeling. She whispered to herself, “Before You alone, Lord, I kneel; not here!”

At that moment, she writes in her notes, “My anxious soul was suddenly filled with gentleness and I heard a voice, which seemed to come at the same time from outside and from the bottom of my heart, tell me, ‘I am the One you seek.’ I fell to my knees. . . .There, behind the church door, I made my first adoration before our Divine Lord present in the Blessed Sacrament.” That is the moment of recognition, of penetrating and humble faith, that we each need.

It may not come through a voice as it did for Mary Elizabeth. It may not come from a miracle, though well-documented stories of Eucharistic miracles abound in our own day. Doctors and scientists, sometimes hardened atheists, convert to Catholicism after

seeing unquestionable evidence of such miracles. Nevertheless, while evidence like that is helpful, it is not living faith. St. James says that “even the demons believe—and shudder” ( James 2:19).

Living faith, rather, comes through the testimony of another, and in this case it is the testimony of God himself, spoken through his Church. It is a well-informed choice to believe that what Jesus promised, what the Scriptures reveal, what the Church teaches, is true. That is the kind of faith that changes a life.

If we wish to love the Mass more, we can start by learning about its fruits. In the Mass we adore and praise God most perfectly. We express our love for God the Father in the Person of his Son and through the Holy Spirit. The priest offers the Holy Sacrifice in persona Christi, the most objectively mystical experience known to man. Priests give thanks on behalf of all humanity, in fact all of creation; the very word Eucharist means “thanksgiving.” We express our gratitude to God especially on behalf of those who do not know him well enough to express their own gratitude.

In the Mass we pray for the needs of all. It is the perfect prayer since it is the prayer of Jesus himself to the Father. Like Aaron and his descendants entering the Holy of Holies with the names of the twelve tribes inscribed on their shoulder vestments (see Exod

28:6–12), the priest crosses the veil into the sanctuary of heaven laden with the needs of his people and those of the whole Church. Holding the Body of Christ in his hands, the priest is holding the Church in his hands and asking the Lord for all her needs. And not just the Church on earth; the souls in purgatory hang on the words of the priest at Mass and are refreshed and renewed by the power of the Holy Sacrifice.

In the Mass we also humbly beg pardon for our sins and those of the whole world. The Mass renews the saving work of Jesus in our time and place. The paschal mystery is the pledge of eternal life, making present the blood of the Lamb that saves us from the angel of death. Once I had the opportunity to offer Mass in a former abortion clinic, in the very room where the gruesome procedures took place. It was a place of almost perfect evil, where the lives of tiny, innocent human beings were snuffed out by the hundreds or thousands. It was clear to me, as I offered that Mass, that that is just where Jesus wanted to be. His light and his healing are meant for the darkest places of the planet, and especially for the darkest places of our hearts.

There are many reasons, then, why we should have reverence and awe before the wonder of the Mass. Important as that is, we something need more. The devils, too, know what the Mass is and are awestruck by it. What we need, we priests and seminarians above all, is to love the Mass. A priest who loves the Mass will, without even trying, help his people love it too. If we have Eucharistic hearts and souls, so will they. In the Mass we form a priestly people, activating the priesthood of the laity and preparing them to assume their Christian role in their families, in the Church, and in society.

We can foster love for the Mass by preaching on it frequently. The patron saint of parish priests, St. John Vianney, was said to have preached so beautifully on the Eucharist that many were converted on the spot. By the end of his life, his voice practically gone, he would open his mouth to preach but words failed him. He simply looked at the Eucharist with tears running down his cheeks, and that was his sermon.

A priest with a Eucharistic heart and soul will prepare his people to receive Communion worthily, generously making confession available and attractive, even at times inviting other priests to hear confessions during Mass. He will make acts of atonement for any sacrilegious Communions that may take place during Mass. He will offer Eucharistic Exposition and Adoration frequently.

If you want to be such a priest, then be such a seminarian. If you love to pray and speak about the Mass now, you will preach on it as a priest. If you attend Mass devoutly and prayerfully now, you will so offer it as a priest. If you receive Communion well now,

you will do so as a priest. The Mass must be the center of our lives here in the seminary so that it will be the center of our lives in the parish.

Father Carter Griffin is a priest of the Archdiocese of Washington. A graduate of Princeton University and a former line officer in the United States Navy, he obtained his doctorate in theology from the Pontifical University of the Holy Cross in Rome. After serving at St. Peter’s parish on Capitol Hill, in 2011 he was assigned to the newly-established St. John Paul II Seminary in Washington, DC, where he now serves as Rector. He is the author of Why Celibacy?: Reclaiming the Fatherhood of the Priest and Cross-Examined: Catholic Responses to the World’s Questions, published by Emmaus Road Publishing.

You Might Also Like

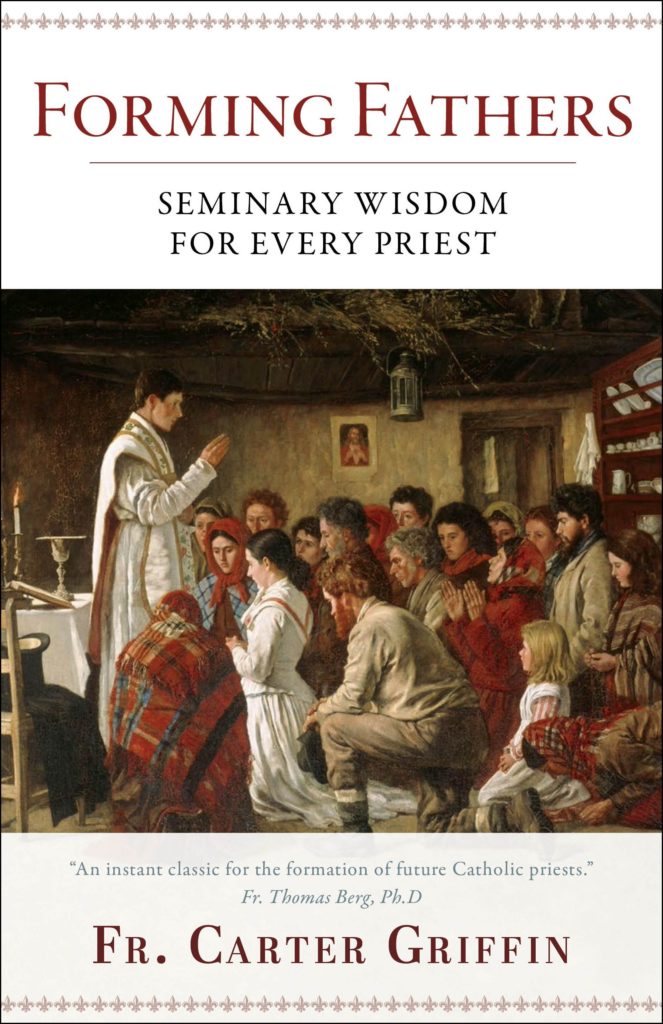

Forming Fathers: Seminary Wisdom for Every Priest seeks to remind priests of the lessons so greatly needed to fulfill their calling faithfully. Originally delivered by Fr. Carter Griffin as talks to seminarians, this series of short, inspiring vignettes can help rekindle a priest’s first love and awaken the aspirations that brought him into the seminary in the first place. Much of what is contained in these pages is also applicable to Catholic laymen, themselves called to the virtues of Christian manhood, the responsibilities of discipleship, and the dignity of spiritual fatherhood.