Do Dinosaurs Prove that Death Existed Before the Fall?

By St. Paul Center

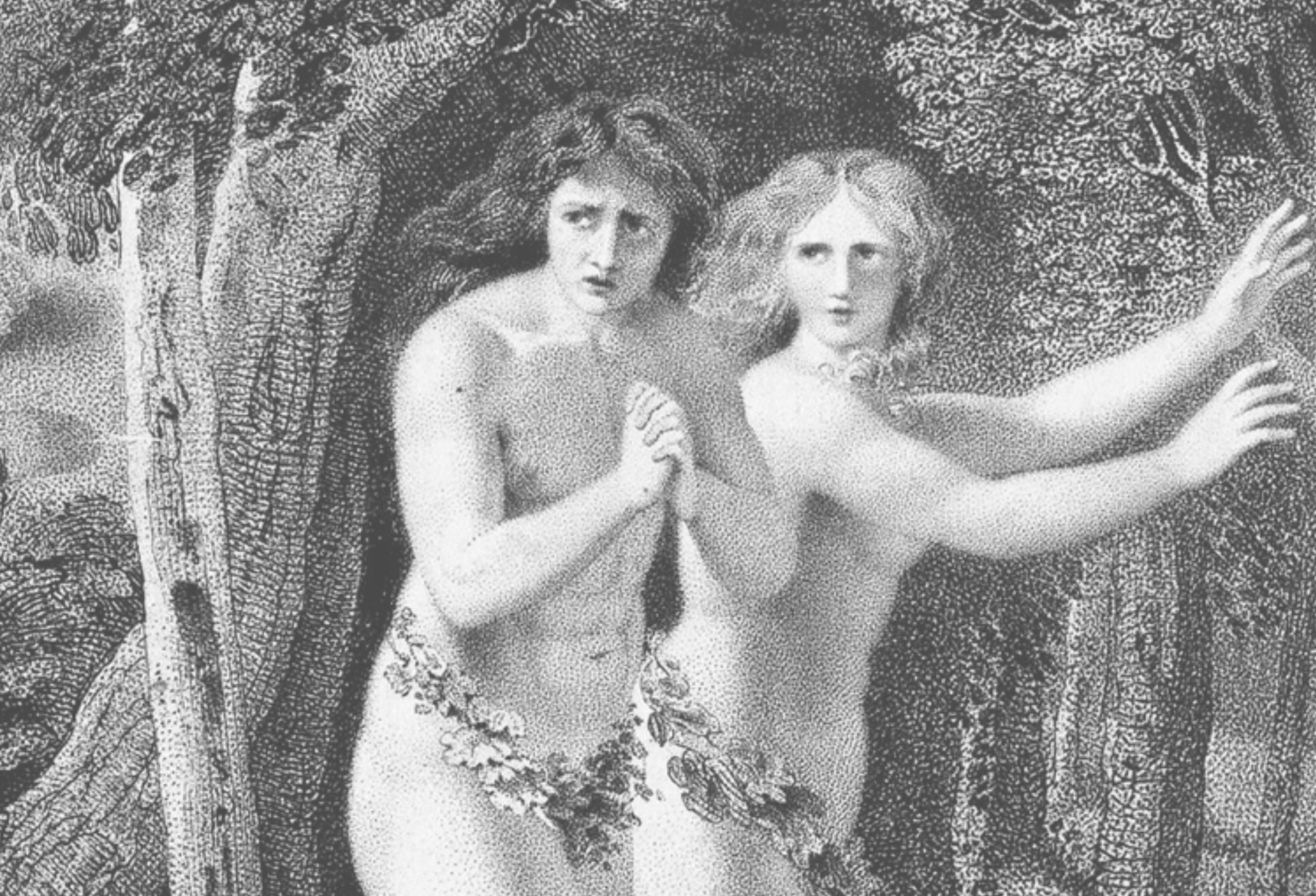

The Bible teaches that Adam and Eve’s sin brought death into the world, but we know from modern science that the dinosaurs lived and died for millions of years prior to the arrival of Homo sapiens. How do Christians make sense of this?

The answer lies in a proper reading of Sacred Scripture. According to the Genesis account, it isn’t animal death in general that comes into the world at the moment of the Fall; rather, it’s specifically human death that is introduced into creation. In the words of St. Paul, “[S]in came into the world through one man and death through sin, and so death spread to all men” (Rom 5:12).

Consequently, when we unearth Tyrannosaurus teeth that clearly didn’t belong to a vegetarian, or when we discover fossils revealing bone cancer in animals that existed 75 million years ago, these findings shouldn’t in any way challenge our faith.

Back in the thirteenth century, long before the birth of modern science, St. Thomas Aquinas had already correctly predicted that the animals must have experienced pain and death even prior to man’s Fall:

In the opinion of some, those animals which now are fierce and kill others, would, in that state, have been tame, not only in regard to man, but also in regard to other animals. But this is quite unreasonable. For the nature of animals was not changed by man's sin, as if those whose nature now it is to devour the flesh of others, would then have lived on herbs, as the lion and falcon. Nor does Bede's gloss on Genesis 1:30, say that trees and herbs were given as food to all animals and birds, but to some. Thus there would have been a natural antipathy between some animals. (ST I. Q. 96. A. 1. Ad. 2.)

Interestingly, we find reasonable grounds for this position not only in natural reason, which Aquinas employs, but also in the text of Scripture itself.

As the Catholic apologist Jimmy Akin has pointed out, the world of Genesis 1-2 is clearly a world subject to entropy. There are stars, for example, which we know operate on life-and-death cycles. Likewise, the fact that Adam and Eve are free to eat from all the trees in the garden (bar one) is proof that their diet included organic things such as fruit—implying that the apples, bananas, and pineapples of Eden would have been subject to digestion and decay.

Aquinas’s vision therefore seems consonant with a world such as this: because stars and dinosaurs and fruit trees lack immortal souls, they were destined to undergo a death of some kind even prior to Adam and Eve’s fatal mistake. (We should also remember that the demons had already sinned before human beings arrived on the scene; the very fact that the serpent is allowed in the garden shows that evil was present even in the prelapsarian land of Eden.)

But for many people this doesn’t get to the heart of the problem. Sure, Aquinas might have correctly predicted the findings of modern science, but that doesn’t help to solve the deeper theological struggle many believers have, namely, why would the world which God created “good” involve so much violence and savagery between animals?

Don’t our hearts recoil a bit at the suggestion that a pride of lions tearing apart a baby zebra is part and parcel of God’s original plan for the world, even before man’s sin? Why should primordial nature be so “red in tooth and claw,” as Tennyson famously put it?

The Christian response to these questions is to understand that even before man’s sin, God created the world in a condition that was wild and untamed. It was a world built in anticipation of what was to come. First, it anticipated the advent of mankind, and the stewardship that human beings would bring (or were supposed to bring) to the planet. But secondly, it anticipates the “new heaven and new earth” (Rev 21:1) which will be realized in the eschaton.

In its origins, therefore, the natural world exists in a state of imperfection and immaturity, but there are good biblical reasons for believing that this state of affairs was not intended to last forever. The Catechism of the Catholic Church explains:

But why did God not create a world so perfect that no evil could exist in it? With infinite power God could always create something better. But with infinite wisdom and goodness God freely willed to create a world “in a state of journeying” towards its ultimate perfection. In God's plan this process of becoming involves the appearance of certain beings and the disappearance of others, the existence of the more perfect alongside the less perfect, both constructive and destructive forces of nature. With physical good there exists also physical evil as long as creation has not reached perfection. (§310)

From the very beginning, God knew that this world would not last forever, nor should it. Rather, it was an imperfect image of the world to come.

It’s also worth clarifying that man’s sin does seem to have played a role in making creation a more violent and deadly place. This makes sense theologically, and it’s alluded to in places like Isaiah 24:2-6. In fact, in his letter to the Romans, St. Paul draws some pretty extraordinary connections between the redemption which mankind awaits, and the extension of that redemption to the entirety of creation:

For the creation waits with eager longing for the revealing of the sons of God … because the creation itself will be set free from its bondage to decay and obtain the glorious liberty of the children of God. We know that the whole creation has been groaning in travail together until now; and not only the creation, but we ourselves (Rom 8:19-23)

At the same time, it would be a mistake to think that animals never killed one another before the Fall. They did. But here we should recall a couple of things.

First, while bestial pain is real, it is nowhere near as bad as the human experience of suffering, since in the case of animals there is no first-person subject (a self-conscious “I”) capable of recognizing that “this pain is being done to me.”

Secondly, we might take consolation in the instincts of Christian thinkers like C. S. Lewis, who felt strongly that the biblical language of a perfectly harmonious creation—“The wolf shall dwell with the lamb, and the leopard shall lie down with the kid … and a little child shall lead them” (Is 11:6)—is more than just a metaphor.

For Lewis and others in the tradition, this language points forward to a future reality which the whole cosmos is groaning for: that second coming of Christ, when all things will be made new, the whole of creation will be reconciled, every tear will be wiped away, and death will be no more.

Further Reading:

Louis Bouyer, Cosmos: The World and the Glory of God (St. Bede’s Press, 1988)

Michael Murray, Nature Red in Tooth and Claw: Theism and the Problem of Animal Suffering (Oxford University Press, 2008)

https://www.ncregister.com/blog/did-dinosaurs-die-before-the-fall

Clement Harrold is a graduate student in theology at the University of Notre Dame. His writings have appeared in First Things, Church Life Journal, Crisis Magazine, and the Washington Examiner. He earned his bachelor's degree from Franciscan University of Steubenville in 2021.

You Might Also Like

Dr. Hahn explores the “covenant love” God reveals to us through the Scriptures and explains how God patiently reaches out to us—despite our faults and shortcomings—to restore us into relationship with his divine family. Join Hahn as he follows the high adventure of God’s plan for the ages, beginning with Adam and Eve and continuing down through the generations to the coming of Christ and the birth of the Church. You’ll discover how the patient love of the Father revealed in the Bible is the same persistent love he has for you. A Servant Book.