Was Jesus Being Unfair to the Pharisees When He Allowed His Disciples to Eat Grain on the Sabbath?

By Clement Harrold

Nobody likes a Pharisee. That being said, there might still be times when we’re tempted to feel a bit sorry for them. A prime example of this comes in Luke 6:1-5:

On a sabbath, while he was going through the grainfields, his disciples plucked and ate some ears of grain, rubbing them in their hands. But some of the Pharisees said, “Why are you doing what is not lawful to do on the sabbath?” And Jesus answered, “Have you not read what David did when he was hungry, he and those who were with him: how he entered the house of God, and took and ate the bread of the Presence, which it is not lawful for any but the priests to eat, and also gave it to those with him?” And he said to them, “The Son of man is lord of the sabbath.”

It’s hard not to feel some sympathy for the Pharisees in this episode. Shouldn’t they be forgiven for thinking the dictates of the Mosaic law ought to trump the eccentric antics of some upstart rabbi from Galilee?

The first thing to realize in response is that the Pharisees’ case isn’t as strong as they would have us believe. When they boldly assert that plucking and eating grain from the fields is forbidden on the sabbath, they apparently have in mind the Old Testament verse Exodus 34:21: “Six days you shall work, but on the seventh day you shall rest; in plowing time and in harvest you shall rest.” For the Pharisees, the implication behind this verse was that reaping grain from the fields was permitted six days of the week, but never on the sabbath.

One thing that is notable about the verse, however, is that it doesn’t forbid individuals from plucking grain on the sabbath to satiate their hunger. Reaping fields on a corporate scale and plucking a few stalks of grain to meet one’s personal needs are two very different things. On a very basic level, therefore, it could be that part of what makes Jesus and His disciples so confident about plucking from the fields on the sabbath is their conviction that the Pharisees have misinterpreted the law.

Here we should bear in mind that the sabbath was designed for giving people the rest they need in order to prioritize the worship of God; it was not designed to prevent people from eating! Indeed, the law explicitly did allow for the needy to take grain from the fields in small amounts (see Dt 23:25), and there are even some Old Testament precedents for the sabbath requirements being suspended in times of necessity, such as in 1 Maccabees 2 when the Jews decide to continue fighting even on their day of rest.

It’s therefore fair to question whether the Pharisees were once again guilty of substituting the edicts of God with the “traditions of men” (Mk 7:8). Because they have failed to grasp the deeper purpose of the law (see Rom 13:10), all they can do is complain every time Jesus diverges from their own particular and all-too-human interpretations. (Notice too how Matthew’s account of this episode, in contrast to Luke, is placed immediately after Jesus’s declaration in Matthew 11:30 that His yoke is easy and His burden light; in other words, Matthew deliberately contrasts the sweetness of the law as properly understood in light of Christ versus the burdensome caricature of the law proposed by the Pharisees.)

So far so good, but what point is Jesus trying to make when He compares His conduct to that of King David? David was a trouble-maker and rule-breaker, so we should be too, right? Wrong! What Jesus is doing in the passage is highlighting the priestly character of King David and His men, and He is implying that He and His disciples are performing the same role.

Here we need to remember that priestly activity constituted the one major exception to the sabbath rules. Whereas everyone else was supposed to cease labor, priests were still expected to perform liturgical functions such as sacrificing animals (Num 28:9-10), keeping the lamps burning (Lev 24:1-4), and replacing the bread of the Presence (Lev 24:8).

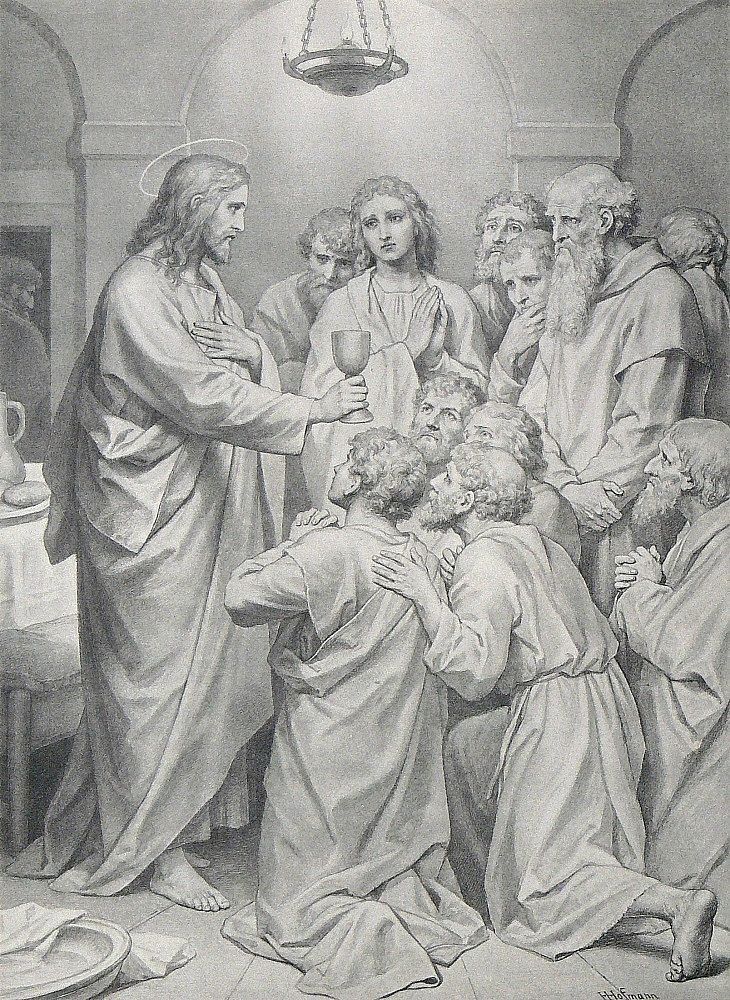

We know, then, that priests were not idle during the sabbath. Indeed, taking care of the bread of the Presence—literally “Bread of the Faces” in Hebrew, also translated as “Showbread”—was one of their essential duties. Sprinkled with frankincense, the bread of the Presence was continually kept in the tent where God dwelt, and it symbolized the enduring presence of God, as well as His nearness to His people. (Interestingly, the lamps in the tent were kept burning 24/7—just like the tabernacle lamps in Catholic churches today.)

Because of this symbolism, it was important to God that the bread be replaced every week, keeping it forever new. According to the Levitical law, therefore, it was on the sabbath day that fresh bread was to be placed in the tent of meeting, and the old bread was to be eaten by the priests “in a holy place” (Lev 24:9). All of this forms the background for Jesus’s reference to the story of King David eating the bread of the Presence, as related in 1 Samuel 21:1-6.

For Jesus, the argument is a simple one. By taking the bread of the Presence and sharing it with his men, David was assigning to himself (and to his followers) a distinctively priestly role. He and his men had been on the run and they were even abstaining from sexual relations in order to prepare themselves for the divine mission that awaited them (see 1 Sam 21:5). As one who has been appointed by God to take over the throne, David realizes that he, the prospective priest-king of Israel, now has the authority to feed himself and his men as they go about their work of restoring the kingdom.

The Pharisees can’t argue with King David, and Jesus knows that. But now He ups the ante by comparing Himself and His disciples to King David and his men. By referencing the story from 1 Samuel 21, Jesus is warning the Pharisees that He and His disciples are priests-in-waiting, charged by God with bringing about the restoration of Israel. In other words, Jesus is asserting that the sabbath exception applies to His disciples, just as it applied to David’s men, because they have received a liturgical mandate from God Himself.

As if this wasn’t audacious enough, Jesus then goes on to make the Pharisees squirm even more with His declaration that “The Son of man is lord of the sabbath” (Lk 6:5). What is that supposed to mean? Pope Benedict XVI sought to answer this question in the first volume of his Jesus of Nazareth trilogy by drawing on the work of the prominent Jewish scholar Jacob Neusner. Though not himself a Christian, Neusner recognized the significance of what Jesus is doing in His exchange with the Pharisees. At one level, Jesus is equating Himself to King David. But at a deeper level, Jesus is revealing Himself to be God.

Consider this question: How can Jesus so confidently make the comparison between David’s experience with the bread of the Presence in the dwelling tent of God, and His disciples’ experience with some ears of grain in a dusty old field? For Neusner, the answer was obvious: Jesus is asserting the reality that He is the new Temple, the new dwelling place of God.

On this reading, therefore, Jesus is not some progressive rabbi seeking to relax the Mosaic laws. In fact, the exact opposite is the case. Jesus is embracing the truth of the law, and making it a thousand times more intense! He is not questioning the authority of the law; rather, He is identifying the source of that authority within His own Person.

What all this implies is that the disciples were justified in eating grain on the sabbath on a number of levels, but none more significant than the reality that their master was Lord of the Sabbath. The Pharisees should have been open to this possibility, but in their hardness of hearts they refused to accept it, instead doing everything they could to catch Jesus out with their own twisted interpretation of the law. Jesus rejects their misconstruals by showing that His disciples have a priestly mission to carry out, and they are not to be deprived of physical sustenance while they go about restoring God’s kingdom.

Whereas David and his men had to eat their bread in the holy place of God’s tent, for the disciples the holy place has become flesh: Jesus is the incarnate Tabernacle, the bodily Temple, and it is in His divine presence that the disciples can eat their grain without fear of breaking God’s law.

Further Reading:

Pope Benedict XVI, Jesus of Nazareth: From the Baptism in the Jordan to the Transfiguration (Doubleday, 2007)

Clement Harrold earned his master’s degree in theology from the University of Notre Dame in 2024, and his bachelor’s from Franciscan University of Steubenville in 2021. His writings have appeared in First Things, Church Life Journal, Crisis Magazine, and the Washington Examiner.

You Might Also Like

Catholics are taught to prize holiness—to admire it in others and to strive for it in their own lives. But we’re never quite told what holiness is. In Holy Is His Name: The Transforming Power of God’s Holiness in Scripture, Scott Hahn seeks to define the term in order to help us better understand our relationship with holiness. Tracing the meaning of holiness first through the Old Testament and then the New, Hahn masterfully reveals how God gradually transmits his holiness to his people—through creation, right worship, and more—and ultimately transforms them through the sharing of his divine life.