What are 10 Things I Should Know About Daniel?

By Clement Harrold

1) He is the last of the four major prophets. Although Jews only count Isaiah, Jeremiah, and Ezekiel among the majors, Christian tradition identifies Daniel—whose name means “God is my judge”—as a fourth.

2) He was taken into exile as a young man. Daniel was one of the many hostages taken from the Jewish aristocracy during the first wave of the Babylonian Exile. Together with three of his close companions—Hananiah, Mishael, and Azariah (or, as they are later renamed by the Babylonians, Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego)—he was forced to leave his homeland of Judah. The biblical book bearing Daniel’s name begins during the reign of King Nebuchadnezzar II of Babylon.

3) He served in both the Babylonian and Persian royal courts. While Daniel spent much of his life under the rule of Babylonian kings, he lived long enough to see Babylon conquered by the Persians around the year B.C. 539 (see Dan 5:30-31). Just as Daniel served with distinction in the courts of the Babylonian rulers, he likewise makes an immediate good impression when the Persians come to the throne—so good, in fact, that his fellow courtiers grow jealous and attempt to have him killed (see Dan 6)!

4) He was a dreamer. Daniel was famous for his prophetic visions as well as his ability to interpret the dreams of others. Daniel 2, for example, recounts the famous scene of King Nebuchadnezzar waking up extremely disturbed following his dream of a male image formed of gold, silver, bronze, and iron. In his dream, a stone then appears, destroying the man and growing into a massive mountain which fills the world. Daniel demonstrates his supernatural gifts when he repeats all the details of the dream, despite the fact that the king never shared them with anybody. Daniel clarifies, too, that the four different metals represent political kingdoms, while the mountain signifies the coming Kingdom of God. Ancient tradition identifies the four metals as Babylon, Medo-Persia, Greece, and Rome respectively.

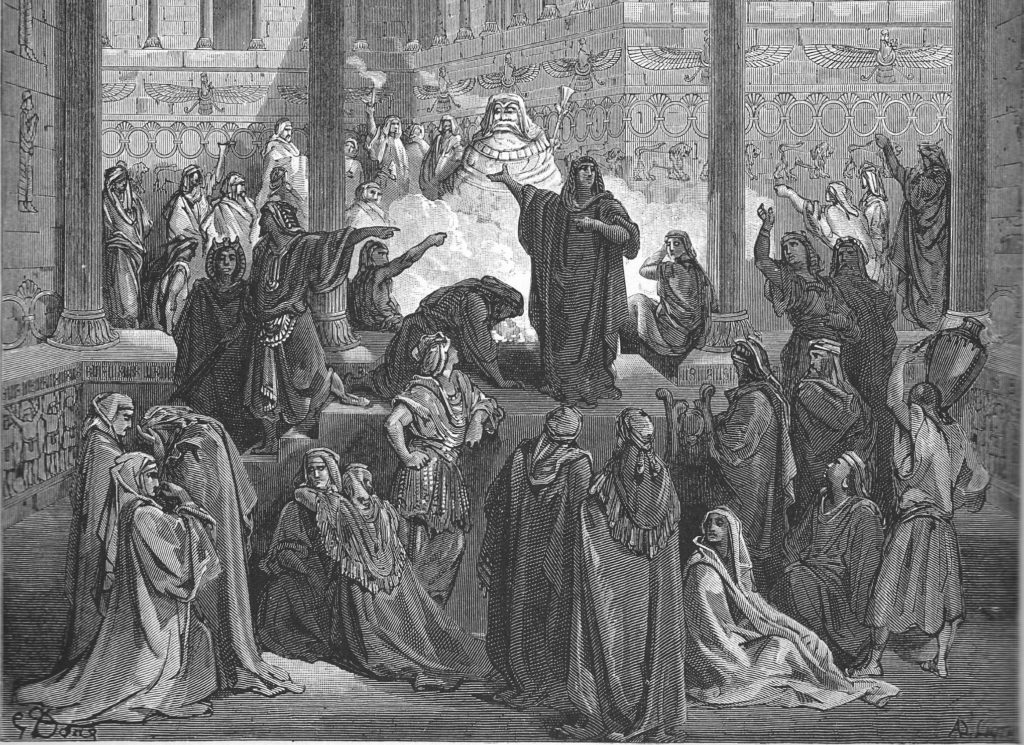

5) His book is the origin of the phrase “the writing on the wall.” The events of Daniel 5 occur many years after the events of Daniel 1-4, and the chapter begins with the famous scene of the Neo-Babylonian King Belshazzar’s feast. Belshazzar has gravely offended God by allowing the sacred vessels stolen from the Jerusalem Temple to be used by those in attendance. Suddenly the loud revelry is interrupted when a mysterious hand appears and begins writing on the wall, hence the origin of the famous phrase! Daniel is summoned, and he interprets the divine script to mean that Belshazzar’s days are numbered (see Dan 5:24-28). Later that very night, Daniel’s interpretation is proven correct when Belshazzar is killed by the Persians.

6) Liturgical purity is a major theme in his writings. Biblical scholars John Bergsma and Brant Pitre have highlighted how the first half of the book of Daniel unveils an ongoing liturgical conflict between the kingdoms of men and the kingdom of God. Repeatedly, the Jewish figures in the story face dilemmas over the demands of right worship, such as when Daniel and his companions refrain from consuming unclean food in chapter 1, or when they refuse to worship the golden idol in chapter 3. Later in his life, Daniel again demonstrates his fidelity to the worship of Yahweh when he disobeys the edict to pray to the Persian King Darius, and is thrown into the lion’s den as a result.

7) He encountered the son of man. Daniel 7 records a massively important vision in which the prophet sees “one like a son of man” approach the “Ancient of Days” and receive from Him an everlasting dominion (see Dan 7:13-14). For many of the Church Fathers, this vision from Daniel was proof that when Jesus refers to Himself as the “son of man,” He was actually emphasizing not so much His humanity, but rather His divinity!

8) He predicted when the Messiah would come. In chapter 9, Daniel offers a famous oracle of the coming of the Messiah (see Dan 9:24-27). Sometimes referred to as the prophecy of weeks, this text garnered huge interest among the Church Fathers because of the specificity of its prediction about when the Messiah would arrive. Although translations of the passage varied in antiquity, both Eusebius and St. Jerome were convinced that the prophecy’s allusion to seventy weeks of years (= 490 years) elapsing between the restoration of Jerusalem and the coming of the Messiah was directly fulfilled by the time span between the rebuilding of the Temple in the B.C. mid-400s and the coming of Christ in the first century A.D.

9) He is a model for how Christians should live in the world. Believers wrestling with what it means to live “in the world but not of the world” can draw inspiration from the example of Daniel and his companions. Despite the avid paganism of the regimes in which they live, these young men show a willingness to participate (often with great ability and talent) in the civil affairs of the empire. But they only ever do so up to a certain point. Like St. Thomas More in sixteenth century England, they repeatedly prove themselves to be “the king’s good servant, but God’s first.”

10) His writings are filled with hope. The setting for the book of Daniel is one of the darkest periods in Israel’s history, a time when the Jewish religion appeared irreparably damaged, and the God of the patriarchs all but defeated. In this gloomy context, the spiritual heroism of Daniel and his companions shines all the brighter. Even after the Jerusalem Temple is destroyed, they prove that God can and should still be worshiped, and their faithfulness is rewarded when the Lord repeatedly delivers them from harm.

Further Reading:

https://www.newadvent.org/cathen/04620a.htm

John Bergsma and Brant Pitre, A Catholic Introduction to the Bible: The Old Testament (Ignatius Press, 2018)

Clement Harrold earned his master’s degree in theology from the University of Notre Dame in 2024, and his bachelor’s from Franciscan University of Steubenville in 2021. His writings have appeared in First Things, Church Life Journal, Crisis Magazine, and the Washington Examiner.

You Might Also Like

Although many Catholics are familiar with the four Gospels and other writings of the New Testament, for most, reading the Old Testament is like walking into a foreign land. Who wrote these forty-six books? When were they written? Why were they written? What are we to make of their laws, stories, histories, and prophecies? Should the Old Testament be read by itself or in light of the New Testament?

John Bergsma and Brant Pitre offer readable in-depth answers to these questions as they introduce each book of the Old Testament. They not only examine the literature from a historical and cultural perspective but also interpret it theologically, drawing on the New Testament and the faith of the Catholic Church. Unique among introductions, this volume places the Old Testament in its liturgical context, showing how its passages are employed in the current Lectionary used at Mass.