What Does It Mean to Be Created in God’s Image and Likeness?

By Clement Harrold

The opening chapter of the book of Genesis famously records God’s decision to “make man in our image, after our likeness” (Gen 1:26). But what precisely do the words “image and likeness” mean? And are humans the only creatures who fit this description?

Something worth realizing from the outset is that the language of “images” (Hebrew, tzelamim) was common in the Ancient Near Eastern milieu in which the book of Genesis was composed. As the Old Testament biblical scholar John Bergsma points out, rulers in this region would often have their tzelamim placed around the empire as symbols of their authority. Analogously, therefore, we should understand that the human race, beginning with Adam, is stamped with divine authority.

A further clue in the biblical text comes a few chapters later in Genesis 5:3, when we are informed that “[Adam] became the father of a son in his own likeness, after his image” (Gen 5:3). This is striking because it is a repetition of the language already used to describe Adam’s relationship to God. The implication? The language of image and likeness is the language of sonship. As human beings we aren’t the natural children of God, obviously, but we are invited to become children of God through divine adoption, which is what takes place in our souls at baptism.

What more can we say here? Taking a philosophical approach, we should remember that a key part of what it means to be created in God’s image and likeness is that we are persons, i.e., living creatures possessing intellect and will, capable of knowing and worshiping God, and gifted with creative powers. The Catechism of the Catholic Church sums it up this way:

Being in the image of God the human individual possesses the dignity of a person, who is not just something, but someone. He is capable of self-knowledge, of self-possession and of freely giving himself and entering into communion with other persons. And he is called by grace to a covenant with his Creator, to offer him a response of faith and love that no other creature can give in his stead. (§357)

Traditionally, theologians have also drawn a subtle distinction between “image” (Latin, imago) on the one hand, and “likeness” (Latin, similitudo) on the other.

According to St. Thomas Aquinas in his Summa Theologiae, image is more closely connected with rationality, personhood, and the ability to know—and therefore love—God in an intentional way. Likeness, by contrast, can be thought of as the perfection of the image; likeness is what is expressed and developed through virtue, whereby we perform good deeds, grow in love, and become ever-greater participants in the divine life of God.

We need to be careful with these distinctions, however, because image and likeness are very much intertwined, and even our “imaging” of God can become stronger or weaker depending on our moral state. As the Catechism notes, “It is in Christ, Redeemer and Savior, that the divine image, disfigured in man by the first sin, has been restored to its original beauty and ennobled by the grace of God” (§1701).

Through our sin, we diminish our likeness to God—meaning we no longer image Him as perfectly as we did at the moment of our Baptism. Here we can think of our souls as being like a mirror. The mirror is always there; no amount of evil can change the fact that we exist as imago Dei, and therefore possess an unparalleled dignity. But the mirror can become dirty and cloudy, meaning we no longer reflect the goodness of God as perfectly as we ought. This is why we need the grace of repentance and sacramental confession.

What about angels and demons? As persons, these spiritual beings are certainly created in the divine image. In the case of the demons, however, the divine likeness has been eradicated; they continue to exist in God’s image insofar as they possess intellect and will, but they totally lack that likeness to God which comes through the pursuit of virtue.

As for the angels, Aquinas notes that there is a sense in which they image the Holy Trinity even more closely than we do, given their superior intellects. On the level of likeness, however, it seems that humans are called to surpass the angels, since it is given to humans alone to “become partakers of the divine nature” (2 Pet 1:4).

Further Reading:

John Bergsma and Brant Pitre, A Catholic Introduction to the Bible: The Old Testament (Ignatius Press, 2018)

Dauphinais, Michael A. "Loving the Lord Your God: The Imago Dei in Saint Thomas Aquinas." The Thomist: A Speculative Quarterly Review, vol. 63 no. 2, 1999, p. 241-267.

https://www.newadvent.org/summa/1093.htm

https://www.catholic.com/qa/how-are-we-the-image-and-likeness-of-god

Clement Harrold is a graduate student in theology at the University of Notre Dame. His writings have appeared in First Things, Church Life Journal, Crisis Magazine, and the Washington Examiner. He earned his bachelor's degree from Franciscan University of Steubenville in 2021.

You Might Also Like

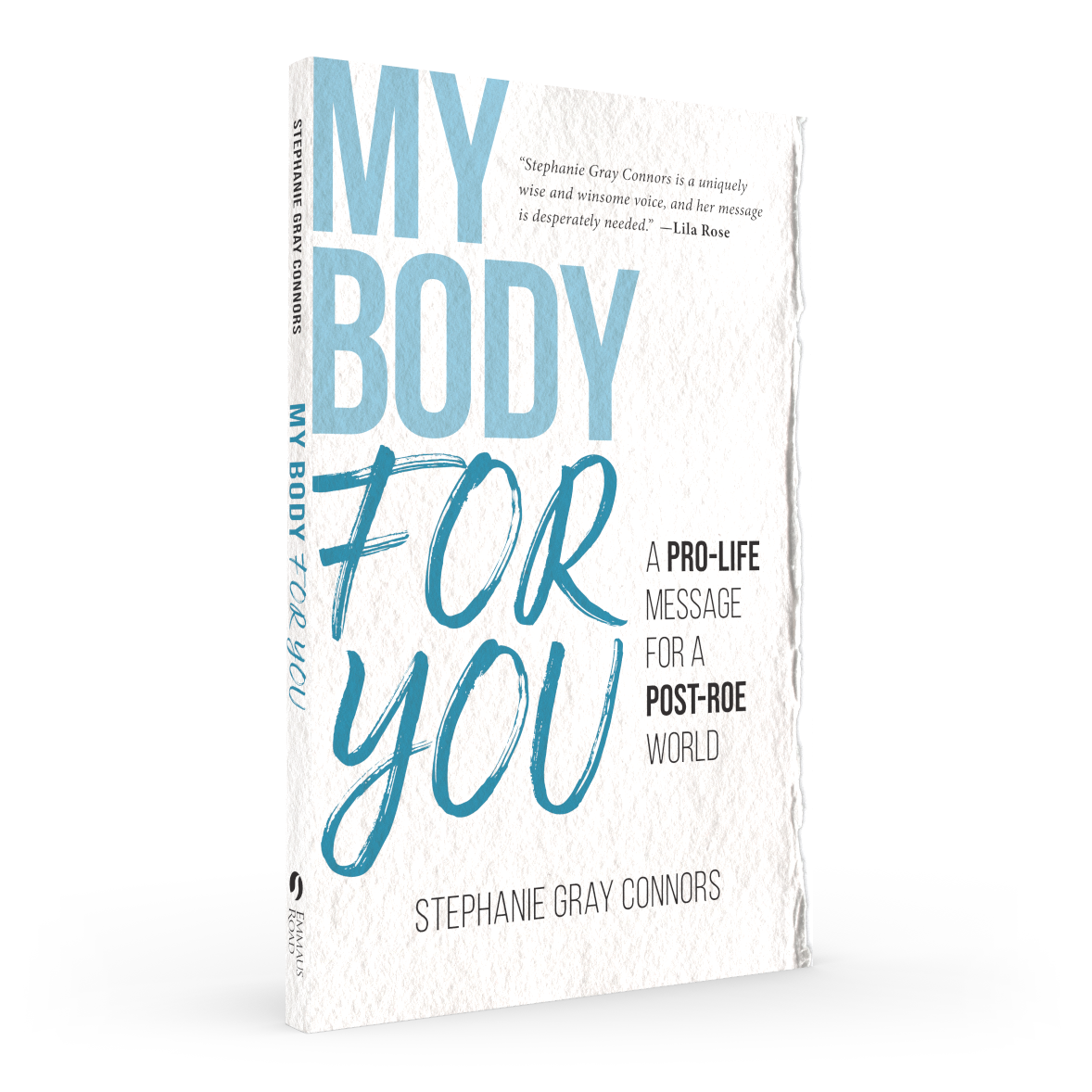

My Body For You by accomplished pro-life debater and activist Stephanie Gray Connors injects new focus and purpose in the pro-life movement.

Diving deeply into common pro-abortion arguments, Connors challenges every reader to see them through the lens of who we are, what we are made for, and why living out Christ’s words—“This is my body, given for you.”—is the secret path to victory for life.

Archives

- ▼2024

- ►December

- ►November

- ►October

- ►September

- ►August

- What Does Jesus Mean When He Talks About Vultures Gathering Where The Body Is?

- What Does Jesus Mean When He Says “Many Are Called, But Few Are Chosen”?

- Why Did Nathanael Believe in Jesus?

- What Advice Does the Bible Offer to Young Men for Overcoming Habitual Vice?

- What Should I Meditate On For The Third Luminous Mystery?

- ►July

- ►June

- ►May

- ►April

- ►March

- ►February

- ▼January

- ►2023

- ►2022

- ►2021

- ►2020

- ►December

- ►November

- ►October

- ►September

- ►August

- What Does the Bible Say about Angels?

- Announcing the Brand New St. Paul Center App!

- Only in Jesus: God’s Personal Invitation

- To Stand with Christ and Defend the Faith

- Where Is Mary's Assumption in the Bible?

- Mid-August Feast: Celebrating the Assumption

- The Problems of the Modern View of Faith

- How Do We Have a Personal Relationship with Jesus?

- You Can't Handle Suffering without the Mass

- ►July

- Sunday Mass and Religious Freedom: A Bishop's Defense

- Stronger Together: Highlights from the 2020 Priest Conference East

- How Do You Explain Why You Believe in God?

- Why Is God Eternal?

- Good News and Special Thanks

- Supporting Priests in Person and Virtually

- You Can Trust God's Goodness

- God’s Plans Are Better Than Ours

- ►June

- Marriage and Family vs the Diabolical

- Our Father: Understanding the Fatherhood of God

- The Church's Eucharistic Mission

- Congratulating Jeremiah Hahn on His Diaconate Ordination!

- A Pure Sacrifice: Why the Mass Isn’t Just Symbolic

- Why Catholics Need Eucharistic Adoration

- The Profound Love of the Eucharist

- Church Teaching on the Real Presence

- ►May

- ►April

- The Eucharist and the Resurrection of the Body

- Our Body is Not a Burden or a Barrier: It’s a Bridge

- What to Do After Lent: Practical Tips from the Church Fathers

- Easter and the Resurrection of the Body

- Historical Questions about the Resurrection of Jesus

- If Christ Defeated Death, Why Do We Die?

- A Holy Week Message: Hope in the Face of Death

- ►March

- We Were Born to Die, but We Were Created to Live

- Preparing for Death

- What Mary’s Yes Means for Us

- What Happens When We Die?

- We Need to be Shaken Up by the Stations of the Cross

- St. Joseph: A Model for Priests

- Don't Forget to Celebrate

- The Meaning of Lent

- Pursuing Holiness with the Saints

- Raising Truthful Children

- Why Should We Care about the Church Fathers?

- Who is St. Perpetua?

- Passing Down the Faith to the Next Generation

- What Can Children Do for Lent?

- ►February

- The Bible and the Church Fathers Launch

- The Meaning Behind Ash Wednesday and Forty Days

- Sneak Peek of The Bible and the Church Fathers

- Seeking God in Darkness

- Prayer to St. Conrad of Piacenza

- Reading the Bible with the Church Fathers

- Called to Holiness

- Finding Profound Love in Eucharistic Adoration

- Do We Take the Bible Literally?

- We Can’t Pray without God

- Am I Really Praying?: Dealing with Distraction

- Benedict XVI on Authentic Reform

- Provisions for the Journey

- ►January

- How the Church Fathers Helped Me Read the Bible

- How to Embrace Mystery

- Do Catholics Read the Bible?

- Is the Bible Just Literature?

- 7 Ideas for Celebrating the Word of God in the New Year

- Highlights from the 2020 Priest Conference West

- The Role of Silence in a Life of Faith

- The Bible and the Fathers

- A Star Shall Come Forth Out of Jacob: Celebrating the Epiphany

- Mother and Queen

- ►2019

- ►December

- Christian Marriage and Divine Love

- Jesus and the Holy Innocents: The New Testament and the Old

- Our Year in Review

- Why We Give Gifts: Gratitude for the Greatest Gift of All

- Why We Read the Genealogy of Jesus

- Son of God, Son of Mary

- The First Prophecy of the Messiah

- The Importance of Christian Story-Telling to Children

- Three Things to Ask Ourselves As We Prepare for Christmas

- Is Santa a Lie?

- The Story Behind "The Attic Saint"

- What We Often Forget about the Holy Family

- Why Do We Call Mary the Mother of God?

- Don't Skip the Advent Traditions

- Preparing for the Guest Who Will Change Your Life

- A Biblical Defense of the Immaculate Conception

- Blessed Among Women: Contemplating the Visitation

- Preparing to Meet Jesus at the End of the World

- What the Bible Says about the Mass

- Is Matthew the Most Important Gospel?

- A Gift for My Savior: Entering Into Advent

- ►November

- St. Andrew Christmas Novena

- Here's to Feasting

- No Bake Cashew and Salted Caramel Ice Cream Cake

- Show Hospitality, No Need to Entertain

- Should Catholics Feast?

- Favorite Thanksgiving Side Dishes

- What Is Moral Therapeutic Deism and Why Does it Fail?

- How to Read a Gospel: The Story of Matthew

- Why Twelve?: The Apostles and the New Israel

- Roasted Potato, Bacon, and Kale Salad

- Building the Kingdom: The Mission of Jesus

- What Modernism Gets Wrong about the Body

- Theology of the Body Beyond the Bedroom

- The Incredible Unity of the Mass

- How Do I Know If I Have a Vocation?: Guidance in Confusion

- Advice for Women Discerning Religious Life

- Augustine on the Eucharist

- The Lost Prophecy of the Eucharist

- Letting Go of Affection for Sin

- ►October

- What the Bible Says about Spiritual Warfare

- Sixth Annual Gala (2019) Highlights

- The Devil Is Real: Combating Spiritualism

- The Truth about Exorcism

- Cultivating Silence

- Christ Is Still Present in the Church

- Fully Human and Fully Divine: Understanding the Incarnation

- Why Catholics Go to Confession

- How Is the Eucharist Both Food and Sacrifice?

- Why Christians Should Keep Caring for the Sick

- Modern Medicine is Based on Christianity

- How to Feast and Fast with the Church

- Does Contraception Violate the Natural Law?

- Debunking the Myths Against Big Families

- Understanding Mary as Queen Mother

- True Devotion to Mary: Avoiding Two Extremes

- How I Embraced Mary as Mother

- Do Our Lives Reflect that We Receive Jesus?

- A Short History of the Rosary

- Mass In Vain: On Not Violating the Second Commandment at Mass

- The Biblical Foundations of the Priesthood

- Celibacy is a Paradox, but a Joyful One

- How to Foster Eucharistic Adoration

- ►September

- When Do We Have to Obey the Pope?

- Grace at the Heart of Grief

- Understanding Vatican II and the One Church of Christ

- Genesis and Evolution

- We Don’t Need to Prove God Is Good

- Where Do We Find Church Teaching on the Real Presence?

- Giving Children the Gift of Our Time

- What Happens When We Put Our Phones Down

- What Does It Mean to Know Someone?

- What Is a Vocation?

- “Jesus Loves You” Sounds Meaningless to a Skeptic: The Problem of Apologetics

- 8 Habits That Will Give You a Better Sunday

- Holy Rest

- An Introduction to the Types of Prayer

- Where Did We Get the Bible?

- Scott Hahn on the Latest Pew Research Center Poll

- The Logic of Gift and the Vocation of Work

- Making Work Meaningful: Three Questions to Ask Ourselves

- The Power of Sunday

- The False Promises of Entertainment

- The Divided Life

- ►August

- What Are the Precepts of the Church?

- Jesus Will Help Carry Your Cross

- Take Up and Read: St. Augustine, the Bible, and the Church Fathers

- Why Do We Have Original Sin if We Didn’t Eat the Apple?

- Word and Presence: On the Importance of the Liturgy of the Word

- Prayer: the Root of the Spiritual Life

- To Serve is to Reign: Mary's Queenship and the Cross

- How to Read the Acts of the Apostles

- Is Celibacy Biblical?

- The Lost Tribes of Israel and the Book of Revelation

- What Is Virtue?

- Is Mary’s Assumption in the Bible?

- Reading with Love: Tips for Sharing Spiritual Books with Children

- Scripture Study and Eucharistic Amazement

- The Sacraments: Chisels in the Hands of Christ

- Why the Eucharist Gives Us the Grace to Avoid Sin

- How God Acts in Our Lives

- In the Order of Melchizedek

- In the Beginning, God Made . . . the Sacraments?

- ►July

- Is Priestly Ordination in the New Testament?

- St. John Vianney Novena for Priests

- Highlights from the 2019 Priest Conference East

- Discerning Our True Desires

- The Importance of Supporting Families

- Commissioned to Preach, Teach, and Baptize All Nations

- Jesus as High Priest: the Significance of the Seamless Robe

- Did You Know You’re a Priest?: the Common Priesthood of the Faithful

- Why We Have a Pope: Defending Papal Succession with Scripture

- St. Joseph: the Model of Supernatural Fatherhood

- The Urgency of Lay Evangelization and the Role of the Priest

- Why Can’t Catholic Priests Get Married?: A Short Defense of the Celibate Fatherhood

- A Priest Answers: Yes, a Celibate Life Can Be Filled with Love

- Should Priestly Celibacy Be Optional?

- Why We Call Priests "Father"

- Why Are Catholic Priests Celibate?

- A Prayer for Government by the First American Bishop

- God Doesn’t Play Poker: Trusting God and Accepting Your True Call

- Why We Should Be Proud to Be Catholic

- ►June

- The Equality of Men and Women in the Church

- The Radical Call of the Sermon on the Mount

- Mary: the Model of Feminine Authority

- More than Meets the Eye: John the Baptist

- Why Don't We Have Women Priests?

- What Replaces Christianity in a “Post-Christian World”?

- Logos, Brands, and Celebrity: the Religion of the Age

- Reason and Revelation

- The Best Books in Our Warehouse

- Beauty: the Remedy to a Culture Gone Numb

- God Invites Us to Call Him by Name

- God Never Leads Us into Temptation

- Learning Perfect Virtue from Jesus in the Eucharist

- Yes, There's a Connection Between Hugging Trees and Keeping the Commandments

- Was There a Time Before Church and State?

- A Break with Human Nature: How We Lost Touch with Ourselves

- In Mastering Nature, We’ve Let Screens Master Us

- Nature Invites Us to Know God

- The Eclipse of Nature: How to Recover Natural Wonder in a Screen-Dominated World

- Creation as Sacrament

- ►May

- Blessed Among Women

- Jesus Reigns in Glory: the Ascension

- How to Read the Book of Revelation

- Read the Book of Revelation for Your Daily Dose of Hope

- Celebrating the Virtue of Loyalty

- All Things in Moderation: Balancing Work and Personal Life

- A Lesson on Vocation from John Paul II

- How a Pope and a President Changed History

- Challenging Students to Understand the Faith Is Not Only Good, It's Necessary

- Morality: More Than Just "No"

- An Introduction to the Sacraments

- What Is Ecclesiology?: An Introduction

- Why the Paschal Mystery?

- An Introduction to Christology

- A New Series for Systematic Study of the Faith

- How Do We Know Who God Is?

- Desiring God Is a Gift from God

- Lessons Learned from Nazareth

- Mary's Saving Motherhood

- Mary: God's Masterwork

- Honoring Mary, Imitating Christ

- Introducing a New Podcast from Scott Hahn and the St. Paul Center

- Do We Need Friends?: Friendship and Following Christ

- Called to Be Children of Mary

- ►April

- Why Can't We Get Enough Superheroes?: Our Need for Adventure

- The Psalms: Music for Our Hearts

- A Venture of Faith

- The Lord Is Risen: Contemplating the Resurrection

- Our Journey with Journey Through Scripture

- Three Books to Read for a Joyful Easter

- Emmaus Day: Behind the Traditional Name for Easter Monday

- The Empty Tabernacle of Good Friday

- The Fourth Cup: Scott Hahn Reflects on the Paschal Mystery

- A Priest's Perspective on Holy Thursday

- Victim and Priest: Christ’s Sacrifice in the Eucharist

- Advice for Overcoming Temptation from the Doctors of the Church

- The Gifts of Confirmation

- A Priest Explains the Signs and Symbols of the Mass

- When John Henry Newman Met the Church Fathers

- The Paschal Mystery: The Source and Power of the Sacred Liturgy

- Who Are the Fathers of the Church and Why Should We Care?

- Understanding the Sacrament of Confirmation

- A Defense of Believing in the Bible: Why the Church Teaches the Bible is Inerrant

- The Eucharist Book Review: Revealing Beauty through the Intellect

- What Does Your Priest Want for Easter?

- ►March

- The Passover, Calvary, and the Mass

- Called to Be Fully Alive

- Being Pro-Life Is Standing with the Rejected Christ

- The Great Commission of Matthew 28

- Understanding the Annunciation

- Mother of the Living: Eve and the Fall

- How to Give Back to Our Priests for Lent

- Story of a Stole: Finding the Priesthood in the Modern Age

- St. Joseph: Noble Lover, Contemplator of Beauty

- What’s the Difference Between a Catholic and a Roman Soldier?

- The Man Behind Two of the Twentieth Century’s Greatest Theologians

- A Defense of Difficult Questions

- Understanding the Spiritual Sense of the Bible

- Love Extravagant: Jesus on the Cross

- Moral Atheism?: What Morality Looks Like without God

- First Friday of Lent Vegetable Bowls

- What We're Reading for Lent

- Jesus Read Scripture: How We Can Follow Our Lord’s Example This Lent

- From Servanthood to Sonship: What the “Our Father” Teaches Us about Covenant

- ►February

- Centering Our Lives on Christ: Wisdom from the Holy Family

- Christ Became a Child to Show Us How to Be Sons and Daughters of God

- Learning from the Holy Family

- What to Bake for Bible Study

- The ABC's of Hospitality

- Tips for Hosting a Bible Study

- Share the Gospel with a Bible Study

- It Is Not Good for Man to Be Alone: Called to Communion

- Surprised by Love

- Six Things to Do Before Lent

- The Seventh Day: Created for Sonship

- It's Not Too Early to Think about Easter

- Hospitals without Hospitality?: the State of Medicine in a Post-Christian World

- Understanding "Hallowed Be Thy Name"

- Salvation History: the Plot of the Bible

- What Happens When Words Have No Meaning

- The Power of Silence

- The Apologist of Apologetics

- ►January

- Catholic Ecology: Living According to One's Dignity

- What Is Social Justice without Personal Virtue?

- What Replaces Christianity in a “Post-Christian World”?

- The Art of Memory in Thomas Aquinas

- Inaugural West Coast Priest Conference Exceeded All Hopes, Serves New Group of Priests

- Everyday Holiness: The Wisdom of St. Francis de Sales

- Drinking from the Font of Mercy

- An Invitation to Life: the Heart of Humanae Vitae

- Detachment: Growing in Freedom

- The Pursuit of Happiness and the Ten Commandments

- Understanding Vatican II and the One Church of Christ

- Walking the Walk: A Guide for the Pilgrim Church on Earth

- Facing Trials with Christ, Grace, and . . . The Lord of the Rings

- The Return to Virtue

- Reclaiming the Excellence of Virtue

- The Adoration of the Magi

- Come Again?: The Eucharist and the Fulfillment of the Kingdom

- The Burning Bush: Theotókos in the Old Testament

- ►December

- ►2018

- ►December

- New Year's Blessings: Looking Back and Looking Forward

- Five New Books to Read in the New Year

- Find Hope in Christ

- The History and Legend of the Church's Villains

- Religious, Not Spiritual: Why Christianity Requires Community

- Do We Take the Bible Literally?

- The Nativity: the Sanctuary of Our Souls

- The Body and the Liturgy: How the Theology of the Body Connects to Prayer

- Why Nero Goes Down as One of the Worst Villains in History

- Birth Control and the Blessed Trinity

- Was Jesus from Bethlehem?: A Biblical Look at Jesus’ Hometown

- The Adoration of the Shepherds

- Son of David: What the Genealogy of Jesus Tells Us

- Why Is John the Baptist Important During Advent?

- Giving Back to Our Priests

- Three Things to Ask Ourselves As We Prepare for Christmas

- The Coming of Advent

- ►November

- Recipe: Beer and Bourbon Shepherdess Pie

- 5 Things to Do with Your Catholic Child(ren) Every Day

- How to Feast and Fast with the Church

- All Salvation Comes through Christ, but Does It Depend on Mary?

- Learning to Listen: Advice for Spiritual Directors

- Recipe: Simple Cauliflower and Gruyere Tart

- Understanding Mary's Perpetual Virginity

- Why We Should Be Proud to Belong to the Universal Church

- Called to Communion: Why We Celebrate Holy Days

- Recipe: Bacon-Jalapeño Macaroni and Cheese

- How to Be the Spiritual Head and Heart of Your Family

- The Complimentarity of Husband and Wife

- What Is 'Feminine Authority'?

- The History of Christian Feasting

- Advice for Women Discerning Religious Life

- What to Know About Marriage Vows

- Encouragement in Our Vocation from Matthew, the Tax Collector

- Unique and Unrepeatable: Finding Your Mission, Finding Your Vocation

- The Burning Truth About Purgatory

- Why Do We Save Saints' Bones?

- ►October

- The Communion of Saints, Indulgences, and Luther: A Primer

- Fifth Annual Gala (2018) Highlights

- The Burning Coal: Eucharist in the Old Testament

- Recovering Halloween

- The Subtle Serpent: Lessons on Spiritual Warfare from the Bible

- Do Catholics Believe in Ghosts?: Church Teaching on Purgatory

- What to Know About Catholic Deliverance and Exorcism

- The Devil Is Real: Combating Spiritualism

- Keeping the First Commandment: How to Avoid Misguided Spirituality in a Culture Hooked on Halloween

- Book Review: The Eucharist

- History and Theology Lead Us to the Church

- The Eucharist: A Model of Perfect Virtue

- Learning Sacrificial Love in the Blessed Sacrament

- Unmasking Popular Spiritualities: What Teresa of Avila Can Teach Us Today

- Praying for Our Leaders: Thoughts from St. Teresa of Avila

- St. Teresa on Sharing Our Weaknesses

- Facing Trials with St. Teresa

- St. Teresa on Spiritual Warfare

- St. Teresa on Detachment

- St. Thérèse's Antidote to Scrupulosity

- St. Thérèse: Peace Is Not the Same as Joy

- Suffering as an Expression of Common Love

- St. Thérèse on Long-Suffering and Prayer

- St. Thérèse's Act of Oblation to Merciful Love

- ►September

- Stewards in the Temple of Creation

- What the Movies Get Wrong About Exorcism

- Going Deeper with Spiritual Direction

- The Journey to God, Explained by the Saints

- Guidance in Prayer from a Spiritual Director

- Freedom for God: Letting Go of Disordered Desires

- Why We Need a Green Revolution, Catholic Style

- What Is Spiritual Direction?: A Spiritual Director Explains

- The Problem of Evil

- How We Got So Confused: Modernism and the Theology of the Body

- Why We Can't Decide: Understanding the Vocations Crisis

- Cardinal Newman Award Dinner Honoring the Rev. George W. Rutler

- It's Time to Save the World Again

- What Would Jesus Say About Modern Medicine?

- Why We Have a Creed

- No Bake Cashew and Salted Caramel Ice Cream Cake

- Jesus Wants Us to Have It All: Reading the Bible in Its Fullest Sense

- The Body of Christ is a Literal Reality in the Church

- Christ Is Still Present in the Church

- ►August

- The Authority of Women in the Catholic Church

- The Catholic Liturgy: Communion with the Sublime

- When Augustine Found God

- St. Augustine's Theology of the Eucharist

- A Recipe for Hospitality: Simple Blackberry Cobbler

- The Queenship of Mary

- St. Louis and a Most Christian Kingdom

- How the Philosophy of History Points to the Lord of History

- Who Is the Woman of Revelation?

- Seek That Which Is Above

- The Assumption of Mary

- A Mid-August Feast: Celebrating the Assumption with Generosity, Patience, and Love

- Unlocking the Stories of Scripture for Children

- Photographer to the Saints

- Rethinking the Joyful Mysteries

- Dog of the Lord

- How One of the Most Devout Students of Scripture Became One of Its Greatest Teachers

- Rediscovering The Sense of Mystery

- Holding Firm to Tradition

- Is the Church in the Bible?

- Food and Good Friends

- ►July

- Signed, Sealed, and Delivered: The Sign of the Cross

- Mary, Our Mother

- Defending Humanae Vitae 50 Years Later

- Marriage and the Common Good

- The Gospel of Sonship: What It Means to Be Part of the Family of God

- The Prophetic Witness of Humanae Vitae

- Applying Natural Law to Contraception

- Genesis on Gender and the Covenant of Marriage

- Theology of the Body Beyond the Bedroom

- The First Society

- A Model of Devotion, a Model for the Priesthood

- John's Revelation: Toward the Everlasting City

- A Priest's Reflection on Sacred Architecture

- What Makes a Great Theologian?

- Why Jesus Wants You to Hug Trees

- The Difference Between Prayer and the Spiritual Life

- ►June

- ►December

- ►2017

- ►2016

- ►2015

- ►December

- ►November

- ►October

- ►September

- ►August

- ►July

- ►June

- ►May

- ►April

- ►March

- ►February

- Scott Hahn - Saint Paul: Persecutor to Apostle

- St. Justin Martyr - Father and Apologist

- Our Lenten Reading List

- St. Ambrose: A Giant of the Faith

- Fasting on Fridays and the Passion of Jesus the Bridegroom

- Booknotes - Truth be Told: Basics in Catholic Apologetics

- Lenten Back to Basics

- Saint Agatha, Virgin, Martyr

- Scott Hahn - Rich in Mercy

- “The Theologian”: Mike Aquilina & Matthew Leonard discuss Gregory of Nazianzus

- BookNotes - Louder Than Words: The Art of Living as a Catholic

- Matthew Leonard - Beer, Chocolate and Embracing Lent

- ►January

- Aquinas: The Biblical Approach of the Model Catholic Theologian

- New Evangelization: The Courtship of Love

- The Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary

- Where is the Eucharistic Sacrifice in the Bible?

- Scott Hahn Explains Papal Infallibility

- “What’s So ‘Great’ about St. Basil?” with Matthew Leonard and Mike Aquilina.

- St. Agnes, a lamb for Christ

- Get the Newest Letter and Spirit

- Joy without Borders

- Scott Hahn - Forty Days

- Matthew Leonard - St. Polycarp’s Most Holy Death

- The Great Witness of St. Perpetua with Mike Aquilina & Matthew Leonard

- Booknotes - St. Monica and the Power of Persistent Prayer

- ►2014

- ►December

- ►November

- ►September

- ►August

- ►July

- ►May

- ►April

- A Throne Established Forever

- Rich in Mercy by Scott Hahn

- More Than A Feeling: The Aura of St. John Paul II

- The “Billy Graham of Scandinavia” Announces His Conversion to Catholicism

- Holy Thursday Mass of the Lord’s Supper

- Jesus’ Triumphal Entry, the Descent into Hell, and the Coming of the Messiah (Palm Sunday, Yea

- Mercy’s Month by Scott Hahn

- “I’m Back!”: The Raising of Lazarus, 5th Sunday of Lent

- Beer, Chocolate and Embracing Lent

- ►March

- ►February

- ►January

- ►2013

- ►December

- ►October

- ►September

- ►August

- ►June

- ►May

- ►April

- ►March

- ►February

- ►January

- Scott Hahn - Saint Paul: Persecutor to Apostle

- Romans: The Gospel According to St. Paul

- St. Agnes, a lamb for Christ

- Leroy Huizenga on Hildegard of Bingen, a New Doctor of the Church

- Pope Benedict speaks on the “depth of God’s love for us”

- New Year, New Book!

- The Theologian

- “What’s So ‘Great’ about St. Basil?” with Matthew Leonard and Mike Aquilina.

- ►2012

- ►December

- ►November

- ►October

- ►September

- Changing the World from a Cave

- Changing the World from a Cave

- New Testament: Sacrifice or Execution

- New Testament: Sacrifice or Execution

- Mystagogy of Marriage?

- Matthew Leonard Explains the Mystagogy of Marriage According to St. John Chrysostom

- What is the New Evangelization?

- What is the New Evangelization?

- Matthew Leonard On St. Gregory the Great

- ►August

- ►July

- Fury of the Idolaters, Beauty of the Faith

- The Heavenly Liturgy in Judaism, the New Testament and the Eucharistic Celebration

- What We're Reading Now: St. Bernard on Song of Songs

- Feast of St. Benedict

- Catholic Church Architecture Part 1 of 10: Architectural Theology

- Jesus as Prophet, His Prophetic Signs and the Last Supper (Podcast and Outline)

- Thomas the Twin

- Seven Upward

- The Early Church. . . Mothers? Mike Aquilina’s Fascinating New Book (w/ Podcast!)

- ►June

- ►May

- ►April

- The Text of the Old Testament

- Perspectives Principles And Criteria: John Bergsma on the Bible in Catholic Theology

- Paul's Strange Mention of Co-Senders: What It Might Mean

- EWTN Live - Benedict XVI and Verbum Domini - Fr Mitch Pacwa, SJ with Dr. Scott Hahn - 03-02-2011

- The Splendor of Eschatology: Highlights from Matthew Levering’s Jesus and the Demise of Death

- Catholic Exegesis: A Streamlined Overview

- Aquinas' Five Reasons Christ Rose from the Dead

- Eighth Day Dawning

- Catholic Interpretation of Scripture

- No Place Like Rome

- ►March

- ►February

- ►January

- ►2011

- ►December

- ►November

- ►October

- ►September

- ►August

- ►July

- ►June

- ►May

- ►April

- Understanding the Book of Acts—Part 3: More Similarities Between Luke and Acts

- The Eucharistic Theology of Early Church Fathers

- Understanding the Book of Acts: Part 2—Acts of Jesus & Acts of the Apostles

- Understanding the Book of Acts: Part 1—“Why Do You Persecute Me?”

- Jesus Didn't Just "Die for Our Salvation": Why He Rose from the Dead

- The Whole Earth Keeps Silence

- Was There a Passover Lamb at the Last Supper?

- Holy Thursday

- Our Big Day

- Presenting a Paper for the Matthew Section at SBL

- ►March

- ►February

- ►January

- ►2010

- ►2009

- ►2008