The Trinitarian and covenantal context in which the human race was created allows us to appreciate more fully that our capacities for knowledge and love are directed toward

our generous self-giving, reception, and union in relations with others. Knowing another person results in that person being in some way present to us or even drawn into us, hence we say that someone is “on our mind” or that we are aware of “what is going on inside” of him. Loving another person moves us to be with him, “to reach out” to him, or to have our heart “go out” to him with the result that we identify with the loved one. These acts of knowledge and love produce a union that is expressed in a willingness to serve the other person and his well-being. When reciprocated, a degree of fellowship is established which sometimes deepens to the point that two persons are said to be “one in heart and mind” or intimate (from Latin for “innermost”). This personal communion can be profound: we speak of a true friend as “another self.”

When that intimacy includes the conjugal union of husband and wife we say that “the two become one.” The mutual generosity by which the persons give themselves and receive each other in these relationships produces a joyous state of well-being that fills them, body and soul, so that we speak of them “coming alive” or being their “true selves” when they are together. In this fashion, the mutual communion and joy of human persons are analogous to the internal communion and joy of the divine Persons of the Trinity.

For human beings, even acts of knowledge and love involving objects (understood here to include non-spiritual creatures) rather than persons can express relations that involve a type of personal commitment and union. For example, someone may become “attached” to an idea, an heirloom, or a pet with such devotion that he considers it “part of himself” and would sacrifice greatly to protect it. Although a reciprocal personal communion is not possible in relation to such objects, personal identification with an object is evidence of a type of self-commitment. In fact, every time a person internally affirms that something is true or false or that it is good or bad he establishes, alters, or reinforces a commitment in relation to it. Whenever a person acts according to what he knows and loves, he further shapes his relations to the objects of his knowledge and love as well as to anyone or anything affected by that action. Thus, the natural purpose of the capacities for generosity, knowledge, and love is to enable the development and gift of a person and the reception of particular persons or objects in and through relations, which in turn shape the development of those persons or objects as well as any others directly or indirectly affected. This capacity for personal commitment, fully realized in communion, is what distinguishes humans from other animals and is the basis for our being embodied images of the Trinity and of Christ and the Church.

It is consequently a monumental error to view the human person’s capacities for generosity, knowledge, and love abstractly or in isolation, outside of relations. As we have seen, these are not neutral “powers” to be used for creating relations according to one’s own “ordering principles” (i.e., auto-nomoi); they are teleological capacities that enable us to commit ourselves as persons in relation to God, others, and the world according to the divinely bestowed nomoi of generosity, wisdom, and love that are intrinsic to creaturely and human existence. Descartes seems to have ignored or been unaware of the absolutely foundational human experience of relations when he sought to ground his philosophical investigations with the affirmation “I think, therefore I am” instead of with “I know and love others, therefore I am.” The still more profound insight, however, would have been to acknowledge the formative role of a person’s relations to family, community, and God by affirming, “I am known and loved, therefore I am.” Had the West followed either of those alternatives, our culture would have been profoundly different. They are natural and revealed perspectives we need to recover in order to foster the authentic development of human persons, families, and societies.

Relations with persons and objects abound in human life. Often, those persons and objects act on us more than we on them, and at times they do so without our consent or conscious awareness. Indeed, much of our life is affected by relations which we have not initiated or knowingly embraced, yet which profoundly shape our identity, thoughts, preferences, and actions. These relations arise from diverse circumstances such as family and culture of origin, physical and mental abilities, educational and employment opportunities, and the political and economic environment. They extend across time and space to people and events before our birth and after our death. Such “non-consensual” relations, as well as the ones we have deliberately chosen, reveal a crucial difference between human and divine persons. The divine Persons exist in the perfect actualization of their eternal Trinitarian relations and,therefore, their identities are complete and unchanging. Human persons, on the other hand, exist within mutable relations and consequently our identities are in a state of becoming, achieving a degree of realization through relations and actions over the course of a lifetime and attaining fulfillment only in perfect communion with God and others in heaven.

When we consider the vast matrix of relations that we have with God, others, and the world, together with the impossibility of ever cataloguing, investigating, and then deliberately choosing to affirm, reject, or modify those relations (if they admit of modification), it might seem that as persons we are not really“ourselves” at all, but merely characters performing roles determined by our de facto relations with others and the cosmos. That, of course, is the interpretation offered by those who think that human beings are nothing more than manifestations of fate, chaos, or the laws of physics, biology, psychology, and sociology. The proponents of autonomy are suspicious and resentful of any order or relation originating outside their free choice as a potential source of alienation or a threat to their dignity. God, however, has revealed that human persons and the universe exist in relation to him as the Creator and Savior who provides for everyone and everything in every circumstance according to his providential plan which directs us in a manner that fully accords with our authentic nature and identity, even in the face of evil and sin.

God’s plan fits us perfectly; it is not foreign or hostile, because it is an expression of the same generosity, wisdom, and love that created us and offers us salvation. In fact, providence has a dialogical rather than a dictatorial quality because God’s gifts of generosity, wisdom, and love are directed to our well-being and by their nature cannot be imposed on us or compelled from us in response. We are neither autonomous nor slaves. We are capable of a personal, cooperative response to the Trinity via the nomoi of generosity, wisdom, and love which orient and enable us inwardly by nature to share in God’s work of creation and by grace to share his life and saving work that will reach fulfillment in heaven. Providence is the covenantal means by which God shapes us, others, and all creation at his initiative while nevertheless enabling us to be participants in shaping ourselves, others, and creation through our responsive self-commitment in generosity, wisdom, and love. This means that as persons we are simultaneously God’s handiwork and his coworkers in the orders of creation and salvation (see Eph 2:10). Had those orders remained intact, we would have reached our full identity as persons without alienation, hardship, conflict, or confusion. Tragically for us, disorder entered the world through sin and with sin came suffering and death.

Fr. Timothy V. Vaverek is a priest of the Diocese of Austin serving as pastor for Assumption Parish in the city of West. His hometown is San Marcos, where he graduated with a degree in physics from Texas State University. During seminary, he studied at the University of Dallas and the Gregorian University (Rome). He received a doctorate from the Angelicum University (Rome) in 1996. His studies focused on Ecclesiology, Apostolic Ministry, Newman, and Ecumenism. Since ordination in 1985, his ministry has been in parishes except for three years as a diocesan official. He has published in various journals and writes for TheCatholicThing.org.

You Might Also Like

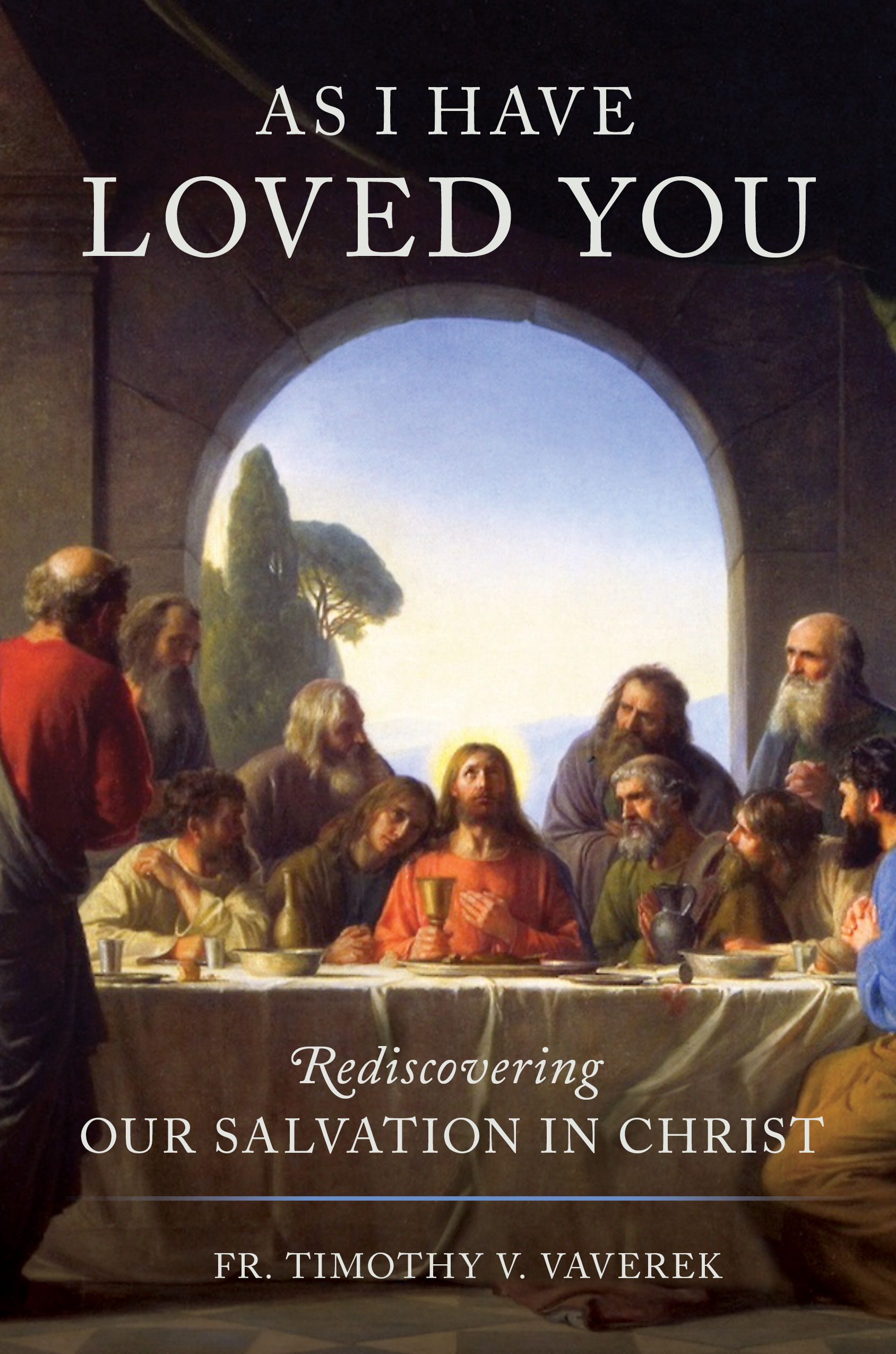

Over many centuries, Christians have lost sight of the heart of the Eternal Covenant: our nuptial union with God in Jesus as members of his Body and Bride. This has fueled a growing crisis of Christian identity and witness. Only by rediscovering the depth and beauty of our salvation in Christ will we be drawn to share more fully in his life and saving mission. But that requires encountering anew the scriptural and early Christian understanding of redemption as a nuptial bond rather than merely a juridical pardon of sin. Beginning with the Trinity’s revelation of himself and his Covenant in the person of Jesus, As I Have Loved You examines our own existence as persons and how the Covenant relationship weds us to Christ in his loving service of God and neighbor. That union prepares us for the Wedding Feast of the Lamb, when we will know and love God even as he knows and loves us.